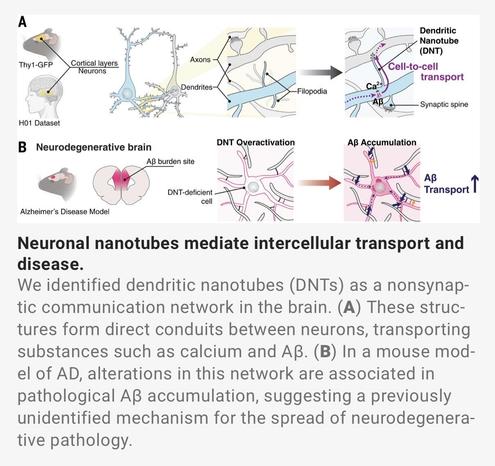

🧠 #Neurons can communicate via a hidden network of #nanotubes, new study finds. Chang et al. (2025) show that dendritic nanotubes (DNTs) are #actin-based #dendrite-to-dendrite conduits transferring Ca²⁺ and molecular cargo (incl. #Aβ), rising before plaque deposition in mouse #cortex. This overlooked pathway may expand our view of neuronal communication beyond #synapses:

#Neuroscience #sflorg

https://www.sflorg.com/2025/09/ns09242501.html

In a breakthrough study, a team of neuroscientists probed the responses of individual neurons in the pulvinar of Japanese macaques as they were shown images of #snakes faces of monkeys, hands of monkeys, and simple geometric #shapes . Sure enough, many pulvinar #neurons responded more strongly and more quickly to snakes than to the other images.

https://aeon.co/ideas/how-seeing-snakes-in-the-grass-helped-primates-to-evolve

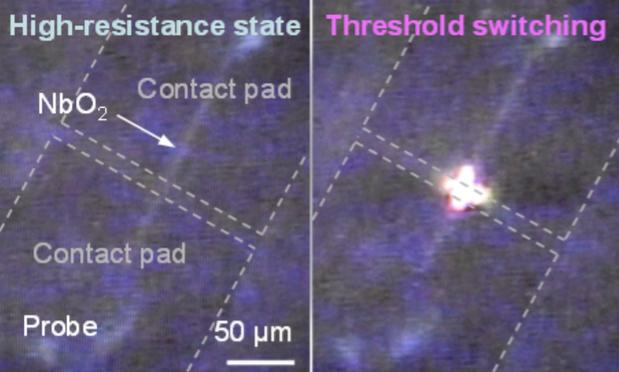

🧠 Electro-optical Mott neurons made of niobium dioxide created for brain-inspired computing

https://techxplore.com/news/2025-08-electro-optical-mott-neurons-niobium.html

#electronics #neurons #manufacturing #biomimetic #engineering #computing

Electro-optical Mott neurons made of niobium dioxide created for brain-inspired computing

Over the past decades, engineers have introduced a wide range of computing systems inspired by the human brain or designed to emulate some of its functions. These include devices that artificially reproduce the behavior of brain cells (e.g., neurons), by processing and transmitting signals in the form of electrical pulses.

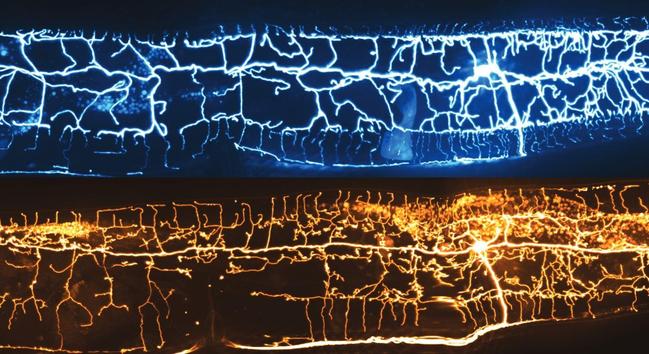

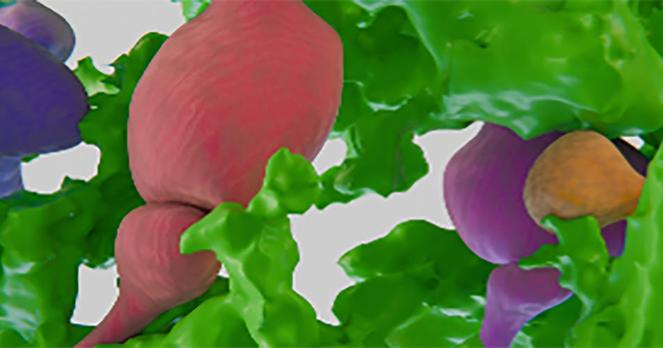

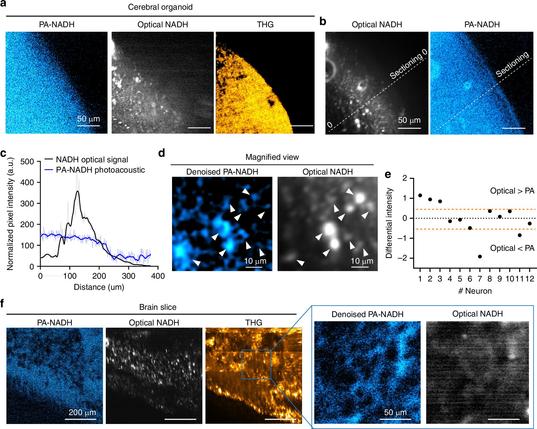

🧠 Imaging tech promises deepest looks yet into living brain tissue at single-cell resolution

https://medicalxpress.com/news/2025-08-imaging-tech-deepest-brain-tissue.html

#biology #brain #neuroscience #microscopy #sensors #instruments #neurons

Imaging tech promises deepest looks yet into living brain tissue at single-cell resolution

Both for research and medical purposes, researchers have spent decades pushing the limits of microscopy to produce ever deeper and sharper images of brain activity, not only in the cortex but also in regions underneath such as the hippocampus. In a new study, a team of MIT scientists and engineers demonstrates a new microscope system capable of peering exceptionally deep into brain tissues to detect the molecular activity of individual cells by using sound.

Braincraft challenge – 1000 neurons, 100 seconds, 10 runs, 2 choices, no reward

https://github.com/rougier/braincraft

#HackerNews #Braincraft #Challenge #Neurons #Neuroscience #AI #Challenge #GitHub

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41380-025-03053-6 #psychiatry #upgrade #HackerNews #ngated

A history of metaphorical brain talk in psychiatry - Molecular Psychiatry

From the very beginnings of our field in the late 18th century, psychiatrists have engaged, often extensively, in “metaphorical brain talk” – rephrasing descriptions of mental processes in unconfirmed brain metaphors (e.g., “diseased working of the brain convolutions”). In the late 19th century, Kraepelin criticized the later developments of such approaches, termed “brain mythology” by the philosopher/psychiatrist Jaspers in 1913. In this essay, I review the history, meaning, and significance of this phenomenon and reach four conclusions. First, this trend has continued to the present day in metaphors such as the “broken brain” and the use of simplistic and empirically poorly supported explanations of psychiatric illness, such as depression being “due to an imbalance of serotonin in the brain.” Second, our language stems from the tension in our profession that seeks to be a part of medicine yet declares our main focus as treatment of the mental. We feel more comfortable with the reductionist approach of brain metaphors, which, even though at times self-deceptive, reinforce our commitment to and membership in a brain-based medical specialty. Third, metaphorical brain talk can also be seen as the “promissory note” of our profession, a pledge that the day will come when we can indeed explain accurately to ourselves and to our patients the brain basis of the psychiatric disorders from which they suffer. Finally, moving away from metaphorical brain talk would reflect an increasing maturity of both the research and clinical aspects of our profession.