Între sisteme și sine – călătoria unui psiholog clinician

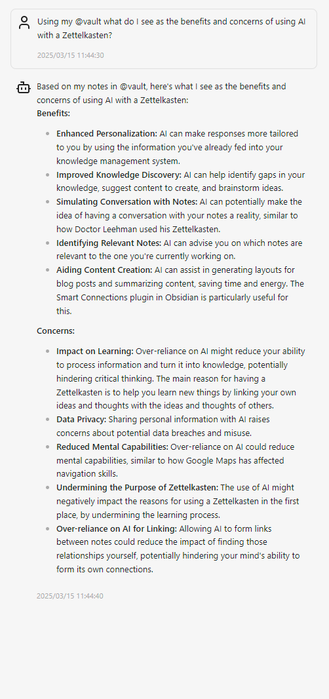

Imagine de: Ana Dumitru

Trăim într-o epocă în care oamenii apelează la știință pentru a se înțelege pe sine. Uneori este vorba de neuroștiințe: scanări ale creierului, neurotransmițători, promisiunea unei chei biologice care să ne elucideze starea de spirit și alegerile. Alteori este vorba de psihologie: poveștile pe care le spunem despre viața noastră, traumele pe care le moștenim, tiparele care se repetă până când învățăm să le vedem. Cele două domenii se suprapun, dar sunt și divergente: unul vorbește în circuite și substanțe chimice, celălalt în metafore și sens.

De multe ori mă aflu prinsă în acest spațiu intermediar. Ca mulți cititori, vreau să le am pe amândouă: claritatea științei și compasiunea terapiei. Vreau să știu ce se declanșează în creier atunci când durerea lovește, dar, la urma urmei, vreau și să știu cum să stau cu ea.

De aceea am vrut să vorbesc cu Ana Dumitru. Este psiholog clinician stagiar de origine română, stabilită acum în Marea Britanie, și și-a făcut o carieră din a sta între lumi: Est și Vest, cercetare și practică clinică, terapeut și ființă umană. A lucrat cu traume complexe, a studiat sănătatea mintală a terapeuților înșiși și a reflectat adesea asupra atitudinilor culturale care modelează modul în care oamenii caută ajutor.

Când spune că terapia este „mai degrabă ca valurile” decât ca o linie dreaptă, nu vorbește doar despre pacienți. Vorbește despre sisteme, despre viața profesională, despre fluxul și refluxul dintre știință și poveste. Și, poate, despre ce înseamnă să fii om.

Desigur, lăsând la o parte gândurile mari despre viață, valuri și tot ce e frumos, există o chestiune mai practică de care trebuie să ne ocupăm: cum devii psiholog clinician în Marea Britanie? Pe scurt, trebuie să faci un doctorat. Dar oricare ar fi așteptările tale legate de ce înseamnă asta, sunt destul de sigură că sunt destul de departe de realitate.

„Programul acesta de pregătire este foarte intens, atât o să zic…”

„Și nu cred că există cineva care să facă acest doctorat și să nu simtă că a fost atât de mult. Nu neapărat ceva rău ca experiență, dar extrem de intens și obositor. Nu ai timp.”

Detaliile pot varia în funcție de fiecare program în parte, dar structura este aceeași: mai multe rotații prin serviciile de sănătate mintală ale NHS-ului (National Health Service – sistemul național de sănătate din UK), cum ar fi cele pentru dificultăți de învățare, sănătate mintală pentru adulți, servicii pentru copii și adolescenți, neuropsihologie și multe altele, desfășurate simultan cu cercetarea academică și participarea la cursuri. Pe hârtie, programul poate părea clar: 3-4 zile de muncă clinică și 1-2 zile de studiu pe săptămână. Dar, după cum spune Ana: „Cum reușești să schimbi atât de des contextul? Este foarte derutant și nu ai niciodată un program bine stabilit.”

Și ce am descris mai sus e doar o mică parte. În primul rând, există latura academică. Spre deosebire de un doctorat în cercetare pură, unde accentul se pune de obicei pe un singur proiect, formarea în psihologie clinică are mai multe niveluri: o teză principală, compusă dintr-o revizuire sistematică și un studiu empiric, care pornește de la generarea ideii, trece prin colectarea datelor, analiză și redactare, plus câteva sarcini mai mici, dar totuși exigente: două studii de caz și o evaluare a serviciilor pe baza datelor clinice.

Apoi urmează și munca pe partea clinică. „La fiecare șase luni, schimbi locul în care te afli, oamenii pe care îi întâlnești, modul în care funcționează serviciul, modul în care își iau notițe în cadrul serviciului. Așa că trebuie să înveți lucruri noi la fiecare șase luni: să cunoști oamenii, să înveți cum lucrează în cadrul serviciului, ce tip de terapie ar putea folosi, populația, care sunt caracteristicile populației. […] Știi, fiecare își face treaba administrativă în mod foarte diferit. Fiecare își face rapoartele în mod foarte diferit. Nu există nicio consecvență între sistemele pe care le utilizează. Cred că acum încearcă să adopte un singur tip de sistem pe care să îl utilizeze în toate serviciile, dar eu a trebuit să învăț cinci sisteme diferite. Evident, asta înseamnă muncă administrativă suplimentară.”

Este un ritm de adaptare continuă, dar în ultimul an anumite lucruri se reduc. Atunci cursanții se specializează într-un domeniu de interes.

„Trauma complexă e, în esență, cam ceea ce pare după nume”

Pentru Ana, asta însemna să lucreze cu traume complexe la adulți. Spre deosebire de PTSD, care apare de obicei din cauza unui singur incident traumatic, „trauma complexă reprezintă, de fapt, o serie de evenimente care duc la asta. De multe ori, este vorba despre persoane care au suferit, să zicem, abuzuri în copilărie, abuzuri domestice, sau care au avut mai multe incidente izolate într-o perioadă scurtă de timp, care s-au acumulat. Ei vor avea unele dintre aceleași caracteristici ca și PTSD: coșmaruri, flashback-uri; dar acest lucru poate afecta și modelele relaționale, pot avea probleme de atașament sau dificultăți în controlarea emoțiilor. Deci, în acest sens, este complex, deoarece este un tipar mult mai pervaziv de traume pe care oamenii le au.”

„O mare parte din munca mea constă în a fi receptivă la ceea ce aduc oamenii”

Nu este deloc surprinzător că terapia pentru traume complexe este, la rândul ei, complexă. Ea implică utilizarea elementelor din mai multe abordări bazate pe dovezi, adaptate individual. „Doctoratul în psihologie clinică se concentrează în mare măsură pe corpul de dovezi, iar în prezent aceasta se referă în principal la CBT (engl.: cognitive behavioral therapy – terapia cognitiv-comportamentală). Însă, în cazul traumelor complexe, există multe terapii foarte utile.

Terapia pe bază de scheme este una dintre ele – implică analiza diferitelor filtre pe care oamenii le pot avea, numite scheme, care se dezvoltă din experiențele lor. Terapia centrată pe compasiune este o altă terapie fantastică. Există DBT, terapia comportamentală dialectică, care a fost dezvoltată special pentru tulburările de personalitate. Este o ramură a CBT. Există terapia de acceptare și angajament. […]

Supervizoarea mea este și ea mai degrabă un terapeut integrativ, se bazează pe o mulțime de modalități diferite și asta fac și eu în munca mea. Cred că asta funcționează cel mai bine cu oamenii. Nu cred că există o soluție universală. Dacă oamenii nu se încadrează într-o categorie, atunci nu este cu adevărat util. Iar oamenii care au suferit traume și abuzuri nu se încadrează într-o categorie sau alta. Nimeni nu se va încadra într-o singură categorie.

Așa că încerc să-mi adaptez abordarea la persoana cu care lucrez și să o centrez pe individ, să mă asigur că ține cont de traume și să lucrez cu un model care se potrivește cel mai bine cu acea persoană. Uneori este vorba de încercări și erori. Uneori, oamenii pot să se conecteze cu anumite elemente, așa că voi integra unele dintre acestea. Dar, de fapt, este o abordare colaborativă. Ei trebuie să-mi ofere feedback și să lucreze cu asta. Nu voi impune niciun model cuiva dacă acea persoană nu se conectează cu el. Așadar, o mare parte din munca mea constă în a fi receptivă la ceea ce aduc oamenii.”

După cum îți poți imagina, desfășurarea unui astfel de tip de activitate, care necesită să fii conectat emoțional, zi de zi, ședință după ședință, necesită multă reziliență. Și vine la pachet cu propriile provocări.

„Ca terapeut, ești adesea un recipient pentru tot ce aduc ceilalți. Cu timpul, asta te erodează.”

În munca sa de cercetare, Ana a investigat cum arată acest lucru pentru terapeuții care au experiență personală de tulburări legate de sănătatea mintală. Deși încă este un subiect oarecum tabu, problema este destul de răspândită: „Studiile pe care le-am găsit în analiza mea bibliografică arătau că, de fapt, mulți terapeuți, dacă nu chiar toți, au fie propria experiență cu tulburările mintale, fie o anumită legătură cu acestea – de exemplu, în copilăria lor, cineva din familie a avut astfel de dificultăți.”

În timpul formării, terapeuții beneficiază de obicei de sprijin prin supervizare, atât din partea mentorului lor, cât și din partea colegilor. „Supervizoarea mea nu se limitează la a mă supraveghea”, subliniază Ana. „Ne întâlnim în fiecare săptămână timp de cel puțin o oră pentru a discuta nu numai cazurile pe care le am, ce am încercat sau care a fost reacția persoanei respective, ci și pentru a discuta despre ceea ce aduc eu în terapie, ce resimt ca urmare a acelei ședințe. Dar există și conceptul de supervizare de către colegi, în cadrul căreia ai la dispoziție un interval anume pentru a discuta cu alți terapeuți din cadrul serviciului. Fiecare aduce cazuri în care s-ar putea să se confrunte cu anumite elemente și toată lumea poate contribui.”

Dar odată ce se termină doctoratul, chiar și această formă limitată de sprijin dispare adesea. „Dacă ești terapeut, ești, știi… super-ok! Și trebuie să «ai grijă de tine», pentru că, evident, lucrezi cu traume și asta este obositor.” În același timp, încercarea de a „avea grijă de tine” și de a cere sprijin are propriile dezavantaje. După cum explică Ana: „Există teama de a fi perceput ca fiind insuficient de competent pentru a-ți face treaba. Dar, de fapt, sunt competentă. Poate că sunt deprimată o mare parte din timp, dar sunt foarte competentă în meseria mea. Așa că îți este pusă la îndoială competența și, brusc, nu mai este vorba de «Hei, poate îți vom reduce numărul de cazuri pentru câteva săptămâni sau poate vei lua o pauză, te vom sprijini». Ci devine o chestiune de «Oh, e sigur să practici?» Așa că mulți oameni nu caută niciodată sprijin.”

Și chiar și atunci când o fac…

„Într-o lume aflată în criză, disponibilitatea de a privi către oamenii care, de fapt, reușesc să se gestioneze singuri o mare parte a timpului…”

Cuvintele se pierd în aer. „NHS este în flăcări”, continuă ea. Desigur, nu este vorba doar de NHS: în toate sistemele de sănătate din întreaga lume, specialiștii medicali sunt lăsați să se descurce singuri în medii care le oferă foarte puțin în schimb. Soluțiile propuse pentru a-i susține includ accesul la terapie pentru terapeuți într-un mod confidențial și accesibil și reducerea stigmatizării față de cei care caută ajutor.

Dar când accentul se pune pe supraviețuire, nu mai rămâne mult spațiu pentru a te ocupa de cei care pot rezista încă puțin. „O să-ți dau un exemplu. În serviciile psihologice există liste de așteptare enorme pentru multe servicii. Așa că ceea ce fac ei este să schimbe criteriile de acceptare în serviciu în acel moment, pentru că se luptă să facă față unui număr atât de mare de oameni. Pur și simplu nu ai suficient personal, suficient timp și suficient spațiu, nici măcar cabinete medicale, pentru a primi oamenii. Așa că le îngreunezi accesul la serviciile tale. Apoi reduci lista de așteptare, pentru că, de fapt, oamenii nu îndeplinesc criteriile. Sau faci evaluări unice, în care îi vezi o singură dată și apoi le spui: «Da, dar nu ești chiar atât de rău. Vino mai târziu.»”

Totuși, puțin este mai bine decât nimic. În ciuda deficiențelor sale, acest sistem epuizat devine mai ușor de apreciat atunci când este comparat cu cele încă în curs de dezvoltare.

„Cred că la baza culturii noastre stă ideea că trebuie doar să faci mai mult, să muncești mai mult.”

„Sunt de acord că există foarte multe presiuni și probleme sistemice în cadrul NHS, dar, pe de altă parte, în România nu avem așa ceva. Așa ceva este… inexistent. Oamenii se plâng că organizăm un grup de anxietate și că au primit doar acești biscuiți sau că durează doar atât sau ceva de genul acesta. Între timp, mă gândesc… noi nu… asta nu există în România. Și aici este gratuit! Primești asta gratuit!”

Din nou, ca în cazul tuturor problemelor sistemice, lipsa unei infrastructuri adecvate este doar o parte a problemei. Deși atitudinea față de sănătatea mintală a început să se schimbe în ultimii ani, mentalitatea dominantă este încă una de respingere și determinare: „Se spune că sănătatea mintală există doar la persoanele cu probleme foarte grave, iar acolo este considerată ceva foarte rău. Dacă suferi de depresie, trebuie doar să treci peste asta. Trebuie doar să nu te mai gândești la asta. Ești deprimat pentru că ești leneș, nu-i așa? Sănătatea mintală nu este recunoscută cu adevărat ca o nevoie a oamenilor și ca un lucru foarte valoros în care să investești. Cred că la baza culturii noastre stă ideea că trebuie doar să faci mai mult, să muncești mai mult.”

În acest context, nu este surprinzător faptul că terapia în sine este adesea înțeleasă greșit. Ideea culturală de „a munci mai mult” și „a trece peste” se infiltrează în așteptările legate de ceea ce ar trebui să fie terapia. Terapia devine un alt lucru pe care trebuie să îl „faci bine”, un alt loc în care trebuie să obții note maxime.

„Terapeutul nu e mecanic; nu te duci acolo cu o mașină stricată, iar mecanicul o repară”

„De aceea terapia este atât de dificilă, de fapt. Dacă te duci la terapie și te gândești: «Oh, este atât de ușor și de minunat, primesc numai note maxime», atunci poate că nu o faci corect. Dar oamenii nu știu asta, pentru că avem o viziune foarte romantică asupra terapiei. Vedem filme, canapeaua freudiană, te așezi, vorbești, ai o revelație și apoi totul se rezolvă. Nu funcționează așa. Nu este liniar.”

Este adevărat că terapia, la fel ca viața însăși, este rareori liniară, dar unde ne duce asta? Așa cum spune Ana, a fi prins între lumi, roluri și așteptări este întotdeauna o luptă. Cheia nu este să scapi de această tensiune, ci să înveți cum să rămâi stabil, să mergi cu fluxul și să îmbini valorile umane cu sprijinul sistemic.

„Este o muncă solicitantă, care se desfășoară în cadrul unor sisteme care sunt ele însele suprasolicitate, dar chiar și în aceste condiții de presiune trebuie să existe spațiu pentru compasiune, autenticitate, reziliență și creativitate. Și cred că terapia este ca viața – rareori este liniară. Lucrurile vin și pleacă. Este mai degrabă ca un val. Uneori vine valul, alteori se retrage, iar după aceea rămâne un sentiment de gol. Și asta este în regulă. Face parte din viață.”

Cum ți s-a părut această postare? Scrie-ne în comentariile de mai jos. Și dacă vrei să ne susții, poți distribui articolul, ne poți cumpăra o cafea aici sau chiar ambele.

Abonează-te la fluxul RSS aici.

Ar putea să-ți placă și:

#călătoriePersonală #mentalHealth #personalJourney #psychology #terapie #therapy