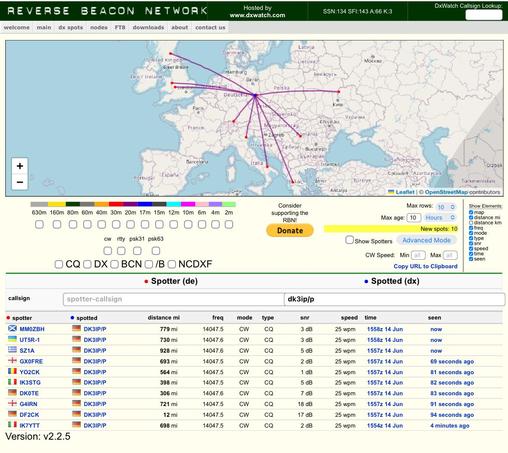

As soon as I arrived on today's first summit the rain stopped: Quirl #POTA DE-0882, DE-0785 (#WWFF DLFF-1068, #GMA DA/SX-192) was followed by Pfaffenstein #POTA DE-0882, DE-0875 (#WWFF DLFF-0745, #GMA DA/SX-295). A big thank you to all the callers for the nice pileup on #40m #ssb while on Quirl - that is something I'm not really used to. And I liked it! #SaxonSwitzerland #Saxony #HamRadio #Amateurfunk #hiking #mountains #qrp #morsecode #20m #2m #70cm #fm #ParksOnTheAir #elecraftkx2 #efhw

Recently started learning #morsecode , although it's completely useless to me. Sometimes it helps to understand why things developed like they did when you go back in time, when remote communication started. And I love having a #lowtech fallbacks.

It's like learning #ed in order to understand concepts of #vim.

A Father's Day Cup of Joe Patio #amateurradio #hamradio #qrp CW #morsecode with the #qcxmini. HAPPY Father's Day.

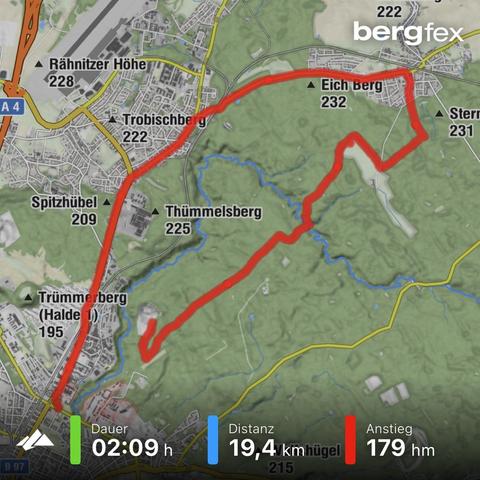

At least I had some #cardio while trying to activate #POTA DE-0393 Dresdner Heide Recreation Park and DE-0932 Lausitzer Schlange National Recreation Trail in @N4JAW style using the bike. The conditions were so bad that no one heard me calling for about 30 minutes. Wish me luck on Monday for the attempt to activate Quirl and Pfaffenstein in #SaxonSwitzerland. #HamRadio #Amateurfunk #QCXmini #20m #morsecode #brompton #qrp #ParksOnTheAir

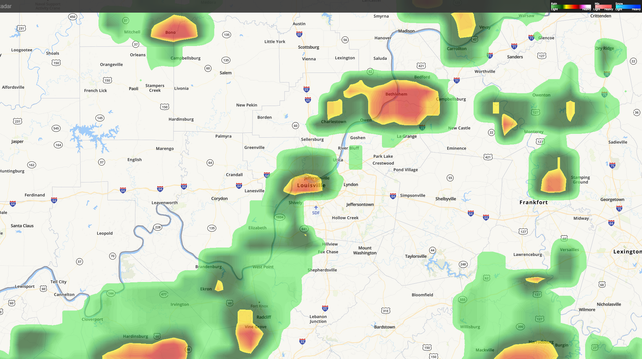

Another Weekend of Terrestrial Storms so its a Cup of Joe Patio #HamRadio #AmateurRadio @skccgroup #SKCCWES CW #MorseCode Weekend with the #FT891 #BencherStraightkey #Telegraphkey

Tough #AmateurRadio #HamRadio Early Bird #POTA #parksontheair CW #MorseCode activation today. #Geomagneticstormc Severe Weather Alert Day, Mowing Crew. I was just waiting for Jason to jump off from the woods on this Friday The 13th.

Using the #KM4CFT 9:1 Unun with #randomwireantenna and @Youkits #hb1b & #ATU10 Autotuner for today's #parksontheair #pota #amateurradio #hamradio CW #morsecode #qrpradio activation on #hawaiianshirt Friday

Now that it was officially announced in "Solid Copy" June 2025, I can show off my plaque for the #CWOps Award for advancing the Art of CW. CW4ever! #morsecode #hamradio https://cwops.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Solid-Copy_2025_June_FINAL.pdf