The thread about Dean Public School; “from the Three R’s to transistors”

Preamble. The schools of the “School Board” era of public education (1872-1918) hold a particular fascination for me, one most profound where they have been “deconsecrated” and are either no longer in use as schools or have disappeared entirely. This thread began as a couple of lines for my own notes about the “Lost Board Schools of Edinburgh” but soon snowballed into an alphabetical deep-dive into each.

Part six of the series of posts looking at “Lost Board Schools of Edinburgh” pays a visit to the former Dean Public School. Judging by the crowds of tourists on phones who gather daily in crowds outside, this must be one of the most Instagrammed of schools. I wonder how many stop for a moment to consider its history and its claim to a unique first in the story of education in the city. So let us take a moment for ourselves to do just that.

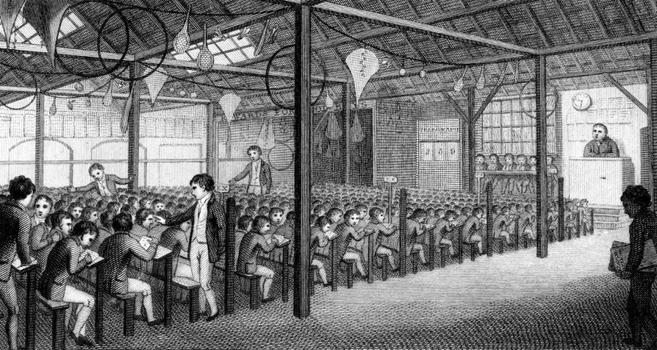

Following the Education (Scotland) Act 1872 (which made schooling compulsory in Scotland between the ages of 5 and 13) the newly elected School Boards undertook a flurry of construction to rationalise, modernise and expand the existing provision. At its formation in 1873 the Edinburgh School Board (ESB) took stock of the situation it had inherited in the city and found there were almost twenty-two thousand pupils being taught in one hundred schools, with the majority run by the various churches. Unsurprisingly the Presbyterians dominated, educating forty-three percent of scholars.

ProviderSchoolsPupilsShareFree Church174,28219.7%Church of Scotland164,22219.4%Heriot’s Hospital163,74217.2%Non-denominational & private203,65416.8%R. C. Church82,0149.3%Episcopal Church91,5187.0%Industrial & free schools, etc.81,4266.6%U. P. Church68573.9%Total10021,715Elementary Edinburgh Schooling in 1873, census by Edinburgh School BoardIn 1873 the Board held a survey of teachers in the city to help prioritise where new schools should be built and the following year held a competition to find architects for its first batch of seven purpose-built schools; Bristo, Causewayside, Leith Walk, North Canongate, Stockbridge, West Fountainbridge and the Water of Leith Village*. The work was divided between the successful applicants, that for the Water of Leith was awarded to Robert Wilson, who would later become the Board’s house architect.

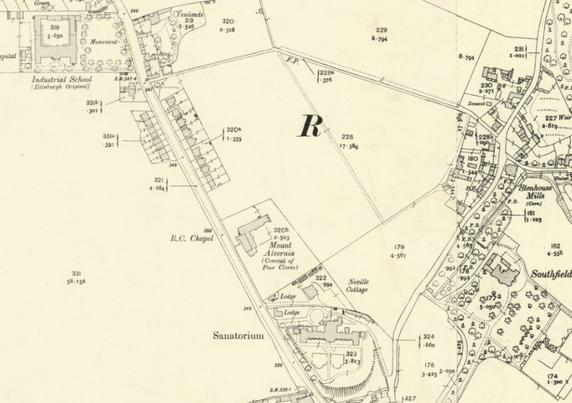

* = The naming and jurisdiction of this school is somewhat confusing. While the area today is widely known as the Dean Village, well into the 20th century it was always known as Water of Leith village. “Dean” referred instead to the old Village of Dean slightly to the north. Both Water of Leith and Dean villages were in the Edinburgh School Board catchment and while the new school was in the former village it was christened Dean Public School at opening. This was most probably in recognition that it served the Dean quoad sacra Parish (an ecclesiastical division, but not a municipal one). To add further confusion, until 1895 there was also a separate St Cuthbert’s and Dean School Board. This covered the western hinterland outwith the city’s municipal boundaries as they then stood and was responsible for schools such as Gorgie, Roseburn, and South Morningside (extension of the city boundary in 1882 meant that the former two schools were actually now in Edinburgh but served by the St Cuthbert’s and Dean Board!)

Water of Leith village, looking northeast past the Bell’s Brae Bridge to Holy Trinity Episcopal Church pre-1875. The school would be built in front of the tall mill building with the circular windows on the left, where the low range sits in this picture. Thomas Vernon Begbie glass negative dated 1887 (incorrect). The Cavaye Collection of Thomas Begbie Prints; City of Edinburgh Council Museums & GalleriesPerhaps because it was the smallest, the Dean Public School was the first of the batch to complete. The opening took place on Wednesday December 8th 1875 making it the first purpose-built school by the Board in the city. The Scotsman reported that at two o’clock, the 150 children of the older division were assembled in the upper classroom in front of the Board and “a large number of gentlemen interested in the work“, including Lord Provost James Falshaw, James Cowan the MP for Edinburgh and numerous town councillors. Following the singing of a psalm and a prayer led by the Rev. Whyte of Free St George’s Church, the Lord Provost gave an opening address and observed that “it was to him a most gratifying circumstance that an auspicious event like the present had occurred during his term of office.”

The roundel of the Edinburgh School Board, “the female figure of education” dispensing knowledge to the young at Dean Public School. © SelfThe Chairman of the Board, Professor Henry Calderwood, mentioned that at this time they had 7,386 children in public education at the nineteen schools under their charge but that most of these were small and overcrowded and there was much work ahead to provide purpose-built accommodation for them. Thanks were given to the kirk session of Dean Free Church for allowing the continued use of their schoolhouse since the 1872 act before the new school was ready.

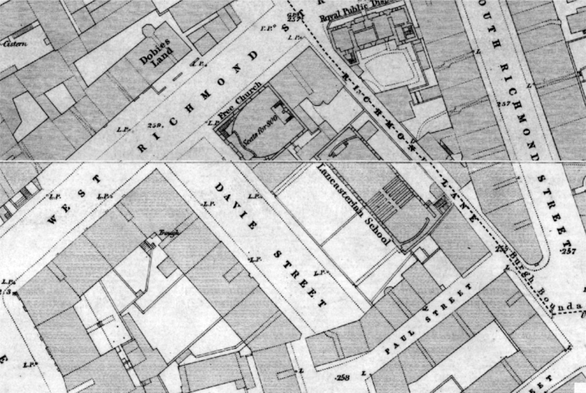

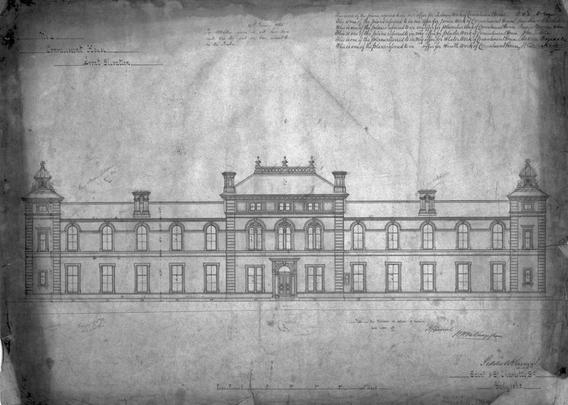

OS Town Surveys of Edinburgh in 1849 and 1876, before and after the Dean Public School was built. Note that at this time the village itself was referred to as “Water of Leith”, as it always had been. Note the Dean Free Church on the old Queensferry Road where schooling took place before 1875. Move the slider to compare. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandThe new school was arranged over two storeys with accommodation for 400 children (using a formula of 10 square feet of space per child). The infants were accommodated on the ground floor and the older children upstairs, each level having a principal large school room (57ft by 23ft, or 17m by 7m) which could be divided by movable glass partitions, as well as smaller classrooms. There were separate entrances for boys on one side and girls and infants on the other, with the playgrounds being similarly segregated. The total cost was £5,740 5s 2d; £1,030 9s 9d for the site and £4,709 15s 5d for the construction work.

Dean Public School in 1950, looking south. The squat gable of Drumsheugh Baths can be seen in the middle distance. Picture CC-by-NC-SA Dean Village Memories, via Edinburgh CollectedAs early as 1878, in a report to the School Board the Inspector complained of overcrowding and a lack of writing desks in the school (those available were sufficient for only 1/3 of the children). This had “spoiled the writing, wasted time in the classes and has prevented the highest discipline grant through the copying traceable to over-crowding“. Failure to remedy these defects would result in the school’s government grant being cut. The school roll at this time was 311, with 200 children qualifying for the Examination in Standard – but the pass rates in these qualifications of 82% for Reading, 84% for Writing and 71% for Arithmetic were the lowest in the School Board. Headmaster Waddell was however praised for his organisation and discipline and the infant department was “in many respects a model one“.

Class portrait of older girls at Dean Public School, with the headmistress Miss Mary Mackenzie (labelled as Hunter). 1883 photograph by J. & S. Sternstein of Glasgow. Note that at least one girl has very short hair, likely the result of it being shaved to combat headlice. Edinburgh and Scottish Collection of Edinburgh City Libraries.Class portrait of boys at Dean Public School, with the headmistress Miss Mary Mackenzie (labelled as Hunter). 1883 photograph by J. & S. Sternstein of Glasgow. Note the boy on the left of Mary seems notably older, taller and better dressed than his peers and may be one of the pupil teachers. Edinburgh and Scottish Collection of Edinburgh City Libraries.Class portrait of boys at Dean Public School with (probably) their headmaster, Esdaile Hunter. 1883 photograph by J. & S. Sternstein of Glasgow. The boy to the left of her is notably taller, older and better dressed than the others and may be one of the pupil teachers, 1883 class photos from Dean Public SchoolThe lack of accommodation was remedied in 1888 with a 3-storey extension for 132 additional children added to the rear, comprising a play-room, a sewing room and an infant classroom. The space beneath was left open and served as a covered part of the playground.

1907 photograph showing the extension added at the rear of the school on the right, adjacent to the bridge. The apparently 17th century structure on the left is Well Court, in fact a late 1880s model workers housing complex in a Scottish Vernacular Revival style by architect Sydney Mitchell. 1907 photograph, Edinburgh and Scottish Collection, Edinburgh City Libraries.When education was made free of charge in 1889 (the 1872 act had introduced fees, although assistance could be provided by the Parish Poor Boards for those who could not afford them), the headmaster at Dean wrote to the School Board to say that the hoped for improvement in attendance rates had not materialised within his district and that “the parents who before were indifferent, are now equally or more so“. In 1894, 120 children were sent to the school from the nearby Dean Orphanage, being reported as “perfect models of cleanliness and order” by the Scotsman and commended in the Evening News for making the school football eleven “a combination to be feared and respected“. They were moved to the new Flora Stevenson School in Comely Bank when it opened in 1901, before being moved back to Dean in 1913 when the new Parish Children’s Home on Crewe Road opened, putting pressure on capacity at Flora’s when there were 115 vacant places at Dean School.

The Dean Orphanage in 1850, recently relocated from its old location beneath the North Bridge where it been in the way of the North British Railway. The community of Bells’s Mill lies beneath and children from both of these locations would attend the Dean Public School. Salt paper print, unknown photographer. Edinburgh and Scottish Collection of Edinburgh City Libraries.With no playing fields or local park to call its own, the school sports days were held at Warriston Playing Fields. In June 1912 the Edinburgh Evening News reported that the pupils from Dean – for the first time in the history of the ESB – had performed mass dancing as part of the day. One hundred and sixty pupils danced “with great zest… danc[ed] a reel to the music of the pipes.”

Pupils of the Dean Public School perform a maypole dance at Warriston Playing Fields as part of their annual sports day, June 28th 1913, Edinburgh Evening News.In December 1914, the staff of the school contributed £1 4s 6t to the Edinburgh Belgian Relief Fund. The following year Robert Peter Smith, assistant teacher, was wounded during at the Dardanelles when serving as a lieutenant with the 1/4th King’s Own Scottish Borderers.

Officers of the 1/4th KOSB in 1915. Robert P. Smith is in the 3rd row, third from the left, the shorter man sporting a moustache. Photo via UK Photo and Film Archive.In 1939 the school was requisition by the War Office and temporarily relocated “for the duration” to the St Mary’s Cathedral Mission Hall on Bell’s Brae, the ancient convening house of the Incorporation of Baxters (bakers) of Edinburgh. It was returned to educational use and in 1953 was placed under the charge of Dorothy Edmond. The new headmistress was determined to raise the school’s profile and instituted a uniform, having a school badge specially commissioned for the blazers.

She rallied parents together and asked for support financially. Although it would not be a lot, it was a lot to some folks and it caused some controversy… Miss Edmund was strict and eventually was held in high regard by both parents and children.

Recollection by pupil Kathleen Glancy of Dorothy Edmond. Via Edinburgh Collected.

Dean School badge, showing the castle of the arms of Edinburgh, open books symbolising learning, the blue of the Water of Leith running through the centre. The Boar’s Head is from the arms of the Nisbet of Dean family, The Cock’s Head may refer to the Poultry Lands of Dean, which in the 17th century conferred the holder the hereditary title of Poulterer to the King. From Kathleen Glancy by Dean Village Memories, CC-by-NC-SA via Edinburgh Collected.But not even the determination of Miss Edmond could counter the significant long term depopulation in the neighbourhood, the result of much of the housing stock being decrepit and condemned combined with the decline of the remaining traditional industries of milling and tanning. In January 1961 the school closed, its roll having reduced to just 37 pupils, less than 10% of capacity. Those remaining were transferred to Flora Stevenson’s and the empty building was leased to the defence electronics company Ferranti Ltd. of Crewe Toll for a period of seven years as a training centre for apprentices and assembly line staff. The Evening News felt it an appropriate symbol of the city’s growing demand for specialist technical education that its oldest public school should have made the transition “from the Three R’s to transistors“.

Christine Robertson, age 10, photographed alone in the school on its last day, 20th January 1961,If you have found this useful, informative or amusing, perhaps you would like to help contribute towards the running costs of this site – including keeping it ad-free and my book-buying budget to find further stories to bring you – by supporting me on ko-fi. Or please do just share this post on social media or amongst friends.

These threads © 2017-2025, Andy Arthur.

NO AI TRAINING: Any use of the contents of this website to “train” generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to generate text is expressly prohibited. The author reserves all rights to license uses of this work for generative AI training and development of machine learning language models.

Ferranti did not require the two basement rooms and these were given over to the use of the Edinburgh Union of Boys Clubs as a base for an outdoor education scheme, the Adventure Centre for Use. A number of Ferranti staff were involved in this, including the works’ own Mountain Climbing Adventure Group for its younger employees. This provided equipment and specialist training to established clubs in activities such as climbing, mountaineering, canoeing and dingy sailing. After Ferranti’s lease was up, in 1969 the school became an annexe to Telford College, whose domestic courses were based nearby at the Dean Education Centre, the former Dean Orphanage.

Dean School in the 1960s. Picture from Dean Village Memories, CC-by-NC-SA via Edinburgh CollectedIn May 1984 the school was disposed of on the open market (offers over £100,000) by Lothian Regional Council and was converted into flats in 1986 by James Potter Developments. Eighteen two, three and four-bedroom properties were created which would have cost between £39,000 and £55,000 when completed.

Former Dean Public School in 2025. Comparison of the photo with that further up the page shows how extra floors were cleverly inserted by reducing the window heights significantly from those of the Victorian schoolrooms. Photo by Fiona Coutts, via Britishlistedbuildings.The previous instalment in this series looked at the Davie Street School(s) in the Southside.

If you have found this useful, informative or amusing, perhaps you would like to help contribute towards the running costs of this site – including keeping it ad-free and my book-buying budget to find further stories to bring you – by supporting me on ko-fi. Or please do just share this post on social media or amongst friends.

These threads © 2017-2025, Andy Arthur.

NO AI TRAINING: Any use of the contents of this website to “train” generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to generate text is expressly prohibited. The author reserves all rights to license uses of this work for generative AI training and development of machine learning language models.

#DeanVillage #Edinburgh #EdinburghSchoolBoard #Education #Ferranti #FurtherEducation #LostBoardSchoolsOfEdinburgh #School #Schools #Written2025