The thread about the Beechmount Institute, home of the Edinburgh Radium Bomb

A couple of things happened recently. A fire at the former Corstorphine Hospital prompted me to read up and write about the history of that establishment and it was also the annual Christian Aid bumper booksale in Edinburgh, at which I picked up an excellent history of the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh1 (amongst many other things.) These circumstances converged to pique my interest in Beechmount, a grand mansion house which was, for a short time at least, the exotic and atomic sounding National Radium Centre and a pioneer in the field of radiotherapy.

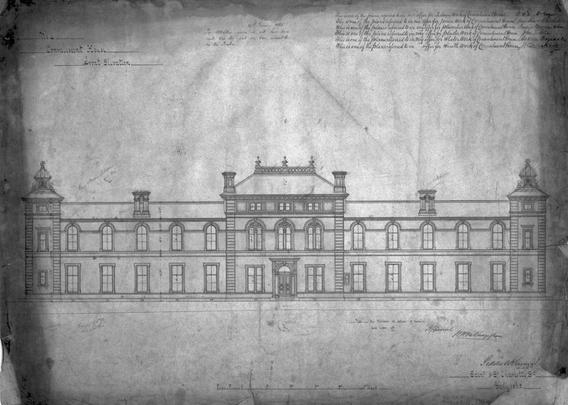

Beechmount, estate agent’s photo. © 2025 Scarlett Land & DevelopmentBeechmount, set amongst 8 acres of woodland, was built in 1900 in an Italianate style to designs by Messrs McArthy & Watson as the private residence of Sir George and Lady Mary Anne Anderson. The land was feud from the Beechwood Mains estate at Murrayfield and its name was a simple amalgam of the neighbouring properties of Beechwood and Belmont.

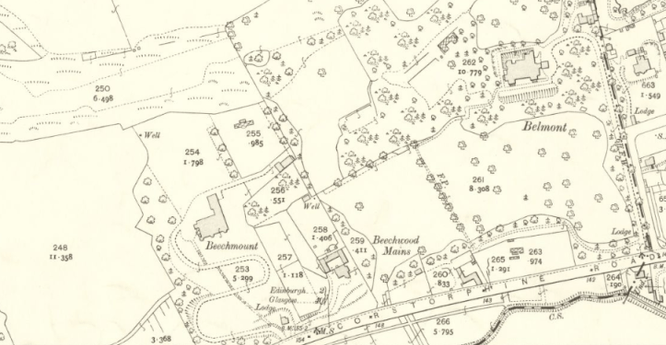

1905 Ordnance Survey 1:25 inch map of Edinburghshire, centred on Beechmount (left), Beechwood (centre) and Belmont (right). Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandSir George was treasurer of the Bank of Scotland from 1898 to 1917, which explains how the coat of arms of that institution came to be found above the house’s main door and grand fireplace. He was the first Scottish “banker knight“, his title conferred for services to his industry. After his retirement in 1917, the Andersons spent their retirement at Beechmount as respected members of Edinburgh society. Sir George died there on December 1st 1923, aged 78. Lady Anne survived him before she too passed away in the house on 26th May 1926, aged 80. Her husband had intended that the house be left to his bank as an official residence for its treasurer but Lady Anne instead bequeathed it to the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. She recommended it be used as a convalescent home for servicemen injured during World War I but gave the hospital managers final discretion as to its use. In addition, £5,000 was left to them to help adapt the property to its new purpose.

Sir George Anderson, 1911 photographic portrait by Bassano & Vandyk. © National Portrait Gallery, LondonAnd that may have been that for the Beechmount story had it not been for the rapid development of a new field of medicine. In 1926, the Infirmary had been able to purchase 500mg of the radioactive element Radium – a substantial proportion of the entire global supply of it at that time – as the result of a donation of £5,000. It began to experiment in its use for the treatment of “malignant disease“; cancer. Prior to this, the only known treatment was surgical removal of tumours and the new branch is what we now call Radiotherapy. To begin with, Radium treatments were undertaken in the main buildings of the Infirmary at Lauriston Place by introducing tiny amounts of the element directly into tumours using needles, different coloured threads attached to them indicating the radioactive strength. However it soon became clear that a specialised unit dedicated to the therapy would be desirable and in 1928 it was decided that Lady Anderson’s bequest should be fitted out as such; the Beechmount Radium Institute.

The medical promise of Radium was great but so too were the costs, dangers and difficulties associated with its use. As a result, in 1929 the government established the Radium Trust to source and hold supplies of the wonder material for the nation and the National Radium Commission to oversee its regulation and distribution. The Commission did not want to deal purely with hospitals and so in 1930 a joint partnership between the Royal Infirmary and the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Edinburgh was set up to combine their teaching and research in the field in order that they could mutually benefit from the national supply. In the meantime £11,000 was spent on the Beechmount project and the new facility, with 36 in-patient beds, was opened in October 1932. To begin with patients continued to be treated at the Infirmary and were sent to the new annexe for their pre- and post-treatment convalescent care, however the entire process was soon centralised at the Institute.

The Beechmount Radium Institute, photograph in the Nursing Times, March 1937The facility was overseen by the respected surgeon John James McIntosh (J.J.M.) Shaw, a military doctor, pioneer in reconstructive plastic surgery and member of both the Radium Trust and Commission. Its first matron was Margaret Colville Marshall, later “Lady Superintendent” of the Infirmary and awarded the OBE for this service. From his base at Beechmount, J.J.M. oversaw the establishment of the Cancer Control Organisation for Edinburgh and Southeast Scotland in 1934, a group of influential (and wealthy) members of society to help organising towards the running costs of the Institute. That same year the Radium Commission approved the Infirmary’s proposal that Beechmount become the National Radium Centre for southeast Scotland, the first of five such centres proposed for the country.

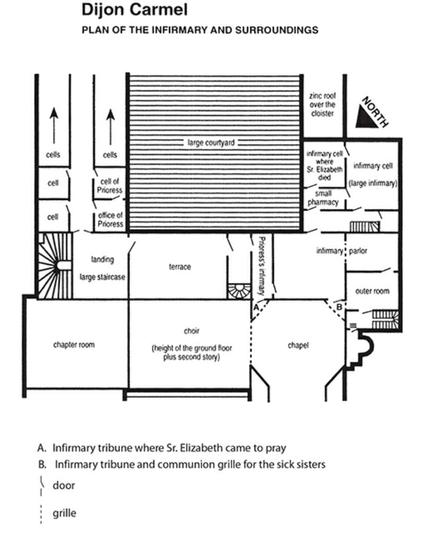

Beechmount on a 1939 Post Office map of Edinburgh, incorrectly labelled as the “East of Scotland Radium Research Institute”. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandWith the support of the Commission an additional 80omg of Radium was acquired and combined with the existing supply to form a mass unit of the material that was called a “Radium Bomb“. This made history as the first such Bomb outside of London and meant that treatments could be made indirectly, focussing the emitted radiation towards the tumour from a few inches away, rather than introducing it directly on needles. This new method was far more efficient and effective and was far safer for both the patient and the medical staff. The Commission also provided funding to pay for the running costs of the Bomb and to safely maintain and house it.

Radium Bomb from Westminster Hospital, London, in the early 1930s, built by E. Rock Carling. The gram of Radium is housed in the egg-shaped, lead-shielded container on the left. It is controlled from a distance by the operator on the right, who can position the head and then open a shutter in the “Bomb” housing to expose the tumour to radiation for a precise amount of time. CC-by-SA 4.0, from the Science Museum’s Wellcome Trust Collection.In 1936, J.J.M. reported that “treatment of malignant disease in certain situations such as the throat by means of the radium mass unit or ‘bomb’ has surpassed anything previously known“. He was joined at this time by Dr Margaret (Peggy) Tod as Honorary Associate Assistant Surgeon. Tod stayed for only a year before moving on to become the Deputy Director of the Holt Radium Institute in Manchester, but made “an outstanding contribution to the pioneering work at Beechmount“. The Infirmary’s capacity to administer radiotherapy increased exponentially as a result of dedicating Beechmount to it; in 1939 it reported over 15,000 treatments had been administered, up from only 907 just five years previously.

Margaret Colville Marshall, 1895-1995, obituary photograph.From 1937, the matron was Jean Ritchie and she served in this post until 1939 when the Institute was closed “for the duration” and re-purposed as a convalescent Auxiliary Hospital; this scheme was directly funded by central government and allowed patients to be removed from the main Infirmary thus freeing up capacity there for dedicated military use or for civilians injured as a result of air raids. The Radium Bomb was removed to the Infirmary and buried at the bottom of a 40 foot deep well shaft to avoid it resulting in a “dirty bomb” in the event it was hit by an air raid. Sadly, Dr Shaw died on wartime active service with the Royal Army Medical Corps in Cairo in September 1940, aged 54, having contracted dysentery while serving as the Consultant Surgeon to the Army GHQ.

Colonel J. J. M. Shaw in his Royal Army Medical Corps uniform. Picture uploaded to Ancestry by Martin Bainbridge.After the war, Radiotherapy in Edinburgh was concentrated at the Western General Hospital and Beechmount was not returned to that use. Instead it remained as a 46 bed convalescent home, operated in tandem with the Corstorphine Home and attached to the Royal Infirmary. In 1974, reorganisation of the medical bureaucracy saw Beechmount detached from the Infirmary and grouped in with other small district hospitals in the Lothians to provide specialist geriatric convalescent care.

One long-standing problem of Beechmount was that the building was accessible from the main road only by a very steep set of stairs or a driveway with multiple hairpin bends. In 1969 an ambulance driver did not correctly apply the brakes of his vehicle resulting in it careering 50 yards down the embankment before progress was arrested by a mature tree. Fortunately the occupants, Mrs Ella Hamersley and Mr Charles Baker, suffered only minor injuries. For the benefit of less mobile visitors to the hospital, members of the Corstorphine Rotary Club used their own cars to provide a shuttle service of rides up and down the gradient during visiting hours.

Beechmount House, estate agent’s photo. The modern wing at the back was that built for staff accommodation when it was converted for medical use © 2025 Scarlett Land & DevelopmentIn 1987 the Lothian Health Board denied that it had plans to either close Beechmount Hospital or convert it into a unit for the specialised treatment of patients with HIV/AIDS. However the following year it proposed the closure and sale of the hospital amid a widespread rationalisation and cost cutting plan. The Board cited the fact that the facility was costing £360,000 a year to run, its opponents countered that the running costs of convalescent hospital beds was only a third of that at major hospitals like the Royal Infirmary or the Western General. But the site was potentially very valuable to developers and with the support of the Secretary of State for Scotland, in what the Daily Record dubbed the “Sick Sale of the Century“, Scotland’s health boards were backed from the top to dispose of a swathe of surplus property on the open market to raise money for their capital budgets. Beechmount was closed in 1989 and the house and grounds were to be sold the following year for £1.8 million. The sale fell through however, as did a scheme to convert it into a Hotel. In 1993 the Health Board intended to build a new dental hospital at Beechmount but found it could not afford the renovation costs of £6 million. The premises were in the interim leased to the Scottish Wildlife Trust who used it for offices and returned to the market and finally sold by the Health Board in 1996, the former staff accommodation being converted into apartments and returned to residential use. It was on the market again in 2018 for offers over £4.5 million but although it eventually sold, it still appears to be without a purpose.

If you have found this useful, informative or amusing, perhaps you would like to help contribute towards the running costs of this site (including keeping it ad-free and my book-buying budget) by supporting me on ko-fi. Or please do just share this post on social media or amongst friends.

These threads © 2017-2025, Andy Arthur

#BankOfScotland #Corstorphine #Health #Hospital #Hospitals #House #Infirmary #Murrayfield #PublicHealth #Radiotherapy #Radium #RoyalInfirmary #Written2025