The thread about the Davie Street School(s); from “Rewards For Good Boys” to “Britain’s most unusual school”

Preamble. The schools of the “School Board” era of public education (1872-1918) hold a particular fascination for me, one most profound where they have been “deconsecrated” and are either no longer in use as schools or have disappeared entirely. This thread began as a couple of lines for my own notes about the “Lost Board Schools of Edinburgh” but soon snowballed into an alphabetical deep-dive into each.

The fifth chapter of our series looking at the “Lost Board Schools of Edinburgh” looks at Davie Street School; with which I made the mistake of proclaiming “there doesn’t seem to be anything interesting about this one” before I had taken a proper look see. Naturally I proved myself completely wrong! And so actually what follows is the quite interesting story of the various schools that have called Davie Street home.

The first school at Davie Street was the Lancasterian School whose foundation stone was laid by the Lord Provost and Magistrates on Monday 12th October 1812. It replaced a temporary home which had been built on the Calton Hill, a “long, low, wood and brick erection“. The school was the work of the Edinburgh Education (Lancasterian School) Society, a charitable institution founded in 1810 by “several respectable Gentlemen…” to address the lack of education for the lower classes of the city by providing it at the “least possible expense of time and money“. It had been determined to use the educational system of Joseph Lancaster, thought it to be both the most economical and the most extensively tested system in practice.

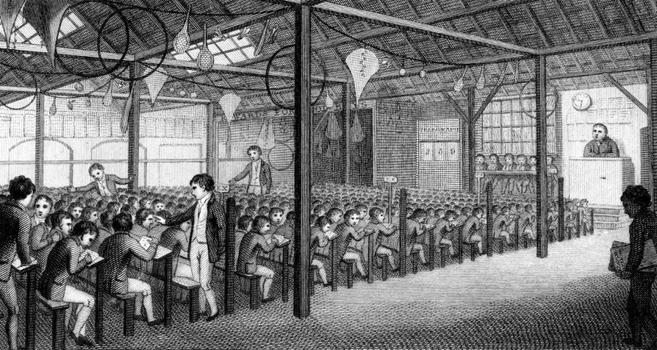

Joseph Lancaster, portrait by John Hazlitt c. 1818 in the National Portrait Gallery, NPG99.Lancaster’s was a Quaker and early pioneer of education for the masses, his schools being highly unusual at the time in being reward-based and almost entirely lacking in punishments. Like the contemporary Madras System of Dr Andrew Bell (familiar to generations of Leithers as the Dr Bell), the Lancasterian System taught large classes in a single “school room” with one teacher supported by multiple pupil monitors. These were older children who relayed the instructions to the younger and kept an eye on their work. The contemporary engraving below shows the pupil monitors walking amongst the rows of younger children, helping them with their work, with the teacher seated on a podium at the front. On the wall a sign reads “REWARDS FOR GOOD BOYS” and the walls and ceiling are hung with toys such as kites, hoops, racket and shuttlecocks, balls and bats which the children could win.

Contemporary engraving of a Lancasterian School – the Royal Free School on Borough Road. The teacher sits on a podium at the front, the children are arrayed in ranks by age (and ability) and the older Pupil Monitors move amongst the rows, relaying the lesson and checking the work.Davie Street had two school rooms, boys and girls being taught separately, sufficient to hold 1,000 scholars and was one of the first steps on the route to a free, mass education in the city. For a subsidised fee of just 2s 6d per quarter, children over 6 years old were taught their Reading, Writing and Arithmetic with the only book in use for teaching being the Bible. However with its Quaker roots, the school was non-sectarian and counted amongst its founding directors in Edinburgh both Presbyterians and Episcopalians. Children were taught the Church of Scotland’s approved Catechism by rote but “the Directors, from respect to the rights of private judgement, do not impose it on children whose parents have conscientious objections to it“.

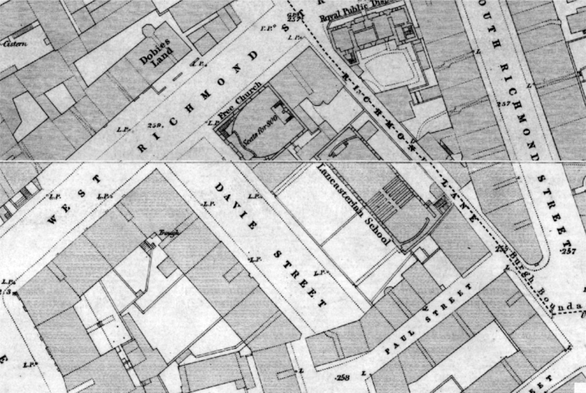

Davie Street showing the Lancasterian School, 1849 OS Town Survey of Edinburgh. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandThe school was “the achievement of the Whigs and of the pious” and was well supported at the highest levels of Edinburgh and Scottish society, as evidenced by the titles of its presidents and directors in the below newspaper advert. It was not universally popular however and according to “Memorials of His Own Time” by Lord Henry Cockburn it was “cordially hated by all true Tories, who for many years never ceased to sneer at and obstruct it.”

Principal office bearers of the Edinburgh Education (Lancastrian Schools) Society in 1812 as published in the Caledonian Mercury.A report of the Committee of Council on Education of 1844 noted that the headteacher, Mr Robert Dun, had supplied “at his own expense, a considerable assortment of philosophical apparatus, with which he performs, before his pupils, the more useful and interesting experiments in Chemistry and Natural Philosophy“. Dun was praised as running an institution being representative “of a well conducted monitorial school“.

There is no educational institution in Edinburgh which does a more extended share of substantial good than the Davie Street Lancasterian School, now 25 years established, and none upon which the public spirited and philanthropic can, to better account, bestow their money.

The school at this time was very much a family affair; it had 200 older boys taught by Robert and an assistant plus 100 infant boys by his father, Robert Senior. 250 girls were taught by John and Miss M. Dun – Robert’s siblings. Including evening classes, the total roll was 622 but it was noted that absence could run high, between 10 to 20 percent. The Duns had joined the school in 1826 and remained there for 35 years until Robert resigned in 1861 and received wide praise for their long-term efforts to educate and better the lot of the poorer children of the city.

Mr Dun, of the Edinburgh Davie Street School, decidedly the best Lancasterian teacher I have yet met, has introduced much useful knowledge into his plan; and, if the means were afforded him, would yet do much more.

James Simpson, “Necessity of Popular Education as a National Object”, 1834

A notable alumnus of the Lancasterian School was George McCrae (1860-1928), later Colonel Sir George McCrae DSO DL VD. A self-made man in the textile and drapery trade, McCrae was knighted in 1908 for his services as MP for Edinburgh East. He is best remembered in Scotland for raising and commanding the 16th Battalion, The Royal Scots during World War 1. This unit, better known as McCrae’s Own, was composed of Edinburgh men and its ranks included 16 members of Heart of Midlothian Football Club as well as players from Hibernian, Raith Rovers, East Fife, St. Bernard’s, Falkirk and Dunfermline football clubs. Much of the rest were drawn from the supporters of these clubs.

George McCrae during his time as an MP, by Sir John Benjamin Stone, 1901At the time of the Duns’ departure the school was proving to be a financial liability for its directors. In that year its expenses were £147 14s 5d but they had raised only £98 9s 7d in subscriptions and fees; outgoings exceeded income by 50%. The Lancasterian School was being kept solvent only by the £900 proceeds of the sale of a bequeathed house. The trustees had therefore been looking to put the institution on a sounder financial footing and in 1857 had proposed to the Governors of the Heriot’s Hospital Trust that it be transferred to their care.

George Heriot’s Hospital (School) in 1966, looking towards the Castle. Edinburgh City Libraries, Edinburgh and Scottish Collection.The Governors in turn remitted the request to a sub-committee who reported favourably on the idea “when the state of funds admitted to an increase“. In the event it was not until 1874 – with the State’s financial support as a result of the Education (Scotland) Act 1872) – that Heriot’s were able to complete the takeover of Davie Street which was to be converted to one of its Outdoor Schools. These schools, instituted in 1838, were outdoor in the sense that they provided education outwith the walls of Heriot’s Hospital itself. They were run on the Madras System and financed by the surplus of the Heriot Trust to provided a free education for the “children of burgesses and others“: in practice this meant the poor.

In October 1874, temporary accommodation was arranged for the non-paying pupils of Davie Street while their school was to be demolished and replaced with a larger and more modern building for 650 children. The architect of the Heriot Trust, John Chesser, drew up plans for a two storey school in a Jacobean style, richly ornamented with the roses and stars from the coat of arms of George Heriot and mouldings and corner towers directly inspired by the mother Hospital School.

Davie Street school as rebuilt by Heriot’s in 1875The school reopened on Whitsunday 1875, the tablet on its principal gable now reading George Heriot’s Hospital School. Its first – and only – headmaster was to be Mr John McCrindle who held this position until his retirement in 1905. The infant headmistress was Miss Jane Johnston from 1877 to 1908, she herself having been educated at one of the Trust’s the Outdoor Schools at Heriot Bridge.

An engraved portrait of John McCrindle by the Edinburgh Evenening News upon his retirement, July 18th 1905In 1879 a tragedy occurred when a pupil, Ellen Bennet, died from burns she had received at the school; on a cold November day she sneaked unsupervised back into her classroom at lunchtime and climbed over the guard of the fire that heated the room to warm herself causing her clothing to catch fire. The following year there were 180 infants and 320 older children on the school roll and “almost all the children… are the boys and girls of parents of the strictly working and artisan classes. They all appeared scrupulously clean and very tidy at the examination“.

Davie Street showing the Heriot’s School, 1876 OS Town Survey of Edinburgh. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandThe school’s life with the Heriot Trust was to prove short lived. In 1886 the Edinburgh School Board agreed to purchase it for £2,368 16s 8d. The Heriot’s schools at Stockbridge (later St. Bernard’s) and Abbeyhill (later Regent Road) were also acquired at this time, the Trust having decided to dispose of all of its Outdoor Schools and move its remaining day scholars to the Hospital itself. The Trust approved the sale and transfer in January 1887, part of the transfer arrangement being that they would continued to fund the free education of its existing scholars – the School Board charged fees, unlike the Outdoor Schools – any pre-existing arrangements for free education, so long as the beneficiary continued to pass the relevant exam standards.

The Board “were not at all satisfied with the internal arrangement” of Davie Street and so spent a further £2,379 2s 9d on expansion and alterations. Their architect, Robert Wilson, added an additional wing to the south with accommodation an additional 130 pupils, increasing its capacity to 690. By re-using the additional ornamental stonework this addition appears almost seamless, beyond the plainer style of the roof line. Despite the change of administration, the “Heriot’s Hospital” tablet remained on its façade, never being replaced by the School Board’s roundel.

Davie Street showing the School Board’s public school, note the large projection of the new wing to the south. 1893 OS Town Survey of Edinburgh. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandThe peace of Davie Street Public School – as it was now known – was breached in October 1889 when a wave of excitement spread throughout British schools via newspaper reports of an attempt by schoolboys in Cardiff to institute a general strike. Their demands were a half-day Wednesday, no homework, shorter hours and no corporal punishment. The action spread contagiously and by the following afternoon the boys of Davie Street had organised themselves, marching behind a banner (reported to be “a handkerchief nailed to a stick“) to Castlehill and Dalry schools in an effort to instigate risings there too. Their demands – reasonable to modern eyes – were conveyed on a scrap of paper; “strike for short hours and no home lessons and free education for the whole school“. The action rumbled on for a few days more with “strikebreaking” pupils at some schools reporting being hissed at the gates by the holdouts before it petered out. Those who were judged to have been ringleaders found themselves punished for their efforts with the tawse – a short, sharp reminder of how things had changed since the days of the reward-based Lancasterian School.

Headline, Evening Mail, 9th October 1889Perhaps memories of the brief uprising of 1889 died hard as in October 1913, once again boys from Davie Street marched out of their school in spontaneous protest in an effort to get their compatriots in the district – at Causewayside, South Bridge and St. Leonards – to join them in resisting rumoured (and entirely spurious) plans to force them to attend school on Saturday mornings.

Life was harsh for many of the children in the Old Town and Southside and a particularly extreme case was reported in the Evening News in November 1908 involving children from Davie Street. Philip Lavin of 150 Dumbiedykes Road was sentenced to three months imprisonment at the Sheriff Court for ill-treatment and neglect of his five children, aged six months to 13 years. He had been repeatedly visited and warned of his conduct by the Scottish Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Children (SSPCC) over the course of five years. Finally, Headmaster R. James Reith wrote to the SSPCC to inform them of bruising on the face of one of Lavin’s daughters which he suspected was the result of assault. Visiting the house again, they found the childrens’ “clothing was scanty and on [their] bed the only covering was an old quilt.” The hungry children had sometimes shared just two rolls between four for their breakfast or five potatoes for their dinner. Lavin earned good money as a painter, 30s a week, but spent it on drink and gave none to his wife, Marion Hewit. She instead had to go out to work for the upkeep of herself and the children and continued to do so when she became ill until collapsing and being sent to the City Fever Hospital suffering from acute consumption (TB). She died less than a year later, on 20th October 1909; her husband however lived until the age of 76.

Boys of Davie Street School in 1910, many barefoot, waiting for tickets for a day trip to Ratho organised by the charitable Courant Fund.In 1917 the School Board undertook an extensive reorganisation of education in the city to provide additional “supplementary education” – that for children over the age of 12 but who had failed to pass the qualification exams for Higher Grade schools. They recognised there was a demand for specialist commercial and technical education at this stage for children who soon be entering the workplace when they finished their compulsory schooling at the age of 14. It was therefore agreed to establish specialist institutes in the city and Davie Street was selected to become part of one of the city’s first specialised supplementary Technical Schools. In 1918, Davie Street closed without ceremony as a primary school and became an annexe for the nearby James Clark Intermediate School.

Former James Clark School with its remarkable corner tower.Initially Davie Street provided rooms for practical subjects such as art, home economics and science while these facilities were constructed at James Clark (which had been planned for elementary education and therefore was not originally built with them). In 1924 it was then taken in hand to be properly modernised (including being converted from gas to electric lighting) and converted into specialist technical workshops for teaching the trades of brassfinishing, tinsmithing, upholstery, plumbing, tailoring and printing. In this guise it provided centralised training in these crafts for the Southside, successful completion of its printing courses could lead to bursaries for a print qualifications at Heriot Watt College and entry into one of the city’s most prized blue collar careers.

An exhibition of work in the printing and allied trades by students of Davie Street in 1957 – a bookbinding for HMS Caledonia is admired.The specialist technical education at Davie Street was moved from the curriculum of James Clark School to those of Telford and Napier Colleges after 1966, its workshops being run-down and moved to those institutions shortly thereafter. James Clark school itself closed in 1972 as part of the citywide secondary education shake-up required to move to a fully comprehensive system; by this time its roll had declined steeply from an inter-war high of over 1,000 to just 300.

Davie Street School in 1959 from the Dumbiedykes Survey by Adam H. Malcolm © Edinburgh City Libraries L973BDavie Street sat vacant for a number of years until it started what was to be an altogether very different chapter in its life story. In 1969 it was turned into the Theatre Arts Centre, the brainchild of Edinburgh Corporation’s drama advisor Gerard Slevin. Slevin approached English teacher Leslie Hills, a self-described “newly minted teacher“, to run this project on the basis that she had upset her school establishment by abandoning the old “chalk and talk” methods and using instead the medium of drama to engage and teach her students. On her first visit to Davie Street she found:

The paintwork was ancient; the boiler was coal-fired and the toilets indescribable. I said yes. I was 23.

Leslie Hills, describing her first visit to Davie Street School

On a shoestring budget, the school was converted to its new purpose which involved removal of a large quantity of old printing machinery, outfitting the hall as a drama studio and cleaning the toilets as best as could be done. With a drama teacher, art teacher and music teacher under Leslie, by the autumn of that year the centre was open for business: “It was an extraordinary position to be in. No-one knew what we should be doing, so we made it all up.”

Edinburgh Corporation’s Theatre Arts Centre sign (Art was a spelling mistake), rescued from Davie Street when it was replaced by a sign for Lothian Regional Council in 1975. Picture kindly provided by Leslie Hills.The first pupils to attend came from the city’s Junior Secondary schools, those destined to be replaced by Comprehensives in the coming years. “Many came from difficult backgrounds, some from the surrounding housing soon to be flattened, where water was obtained from a tap in the yard. Many were underfed, ill-clothed for Edinburgh’s winters and, leaving school at 15, just too wee to be sent, bewildered, out to scrapyards and tyre depots with a bit of paper on which was written an address in a part of town of which they had no knowledge.“

Slum housing in Edinburgh, 1969. Marshall’s Court, Greenside, . S. G. Jackman photo, Edinburgh City Libraries, Edinburgh and Scottish Collection.Up to 500 secondary-age children a week came through the doors of the Theatre Arts Centre from across the city, including from “List D” reformatory schools, those pushed to the very extremes of the education system. Leslie Hills takes up the story:

I talked to every class on their first day, explaining that we did not use the belt – still in use in schools – and that the rules were behave yourself and no graffiti – except in the toilets into which they were allowed to take felt-tipped pens which were in plentiful supply. The boys’ toilet became a wonder to behold – absolutely covered in intricate designs. I never worked out how they did the ceilings. The rest of the building remained pristine.

With its radical approach to learning through the mediums of drama, art and music, the laid back approach to uniform, lesson structure and timetabling and the lack of corporal punishment, the “school-in-a-theatre” was dubbed “Britain’s most unusual school” by the Daily Record. It was a fitting coincidence that Davie Street School had unwittingly been returned to its roots of education without punishment.

Drama teacher David Prince is “attacked” by his pupils at the Theatre Arts Centre in an exercise learning about the value of movement in drama. Daily Record, 2nd December 1970The initial success of the Theatre Arts Centre gamble allowed the facilities and services on offer to be improved. Finding out from the Corporation’s painters that they didn’t need to follow the official schools’ colour palette of mushroom and cream, re-painting made use of colour. One room was colour drenched in pale green and fitted with an epidiascope and light box for projecting and copying designs for poster; An in-house theatre company – Theatre in Education – was set up who undertook outreach visits to city schools; A technician and a van was acquired to run a stage equipment lending library; The curriculum was widened to include photography, printing and film; Evening drama clubs for teenagers were run and later, Edinburgh Youth Theatre found a home here and it was a regular performance venue during the annual Festival Fringe.

The reorganisation of local authorities in 1975, the Centre became part of Lothian Regional Council and the geographical remit expanded accordingly. Leslie Hills departed in 1980. Ten years later it survived a threat to its continued existence at Davie Street when the site was short-listed as a potential location for a new medical centre for the district. It was announced in 1993 that a central arts school for Lothian Region would be created in the former Leith Academy building on Duke Street, which would have seen Davie Street closed and relocated there. This plan never came to fruition, likely as the result of Lothian Region losing control of its further education colleges later that year. Having survived these threats, it was the Local Government etc (Scotland) Act 1994 – which abolished Lothian Regional Council in 1996 – that did for the Centre. It was closed by the new, unitary City of Edinburgh Council in 1997 when the Secretary of State for Scotland, Michael Forsyth, refused to provide sufficient funding to the newly established councils. Dr Bell’s Drama Centre, the primary-age equivalent of the Theatre Arts Centre was closed at the same time. A “cheery wake in the rather battered studio” was held by staff past and present to celebrate its 28 year life, which also marked the end of 185 years of continuous educational use of the site.

Over the next three years the Council sought to dispose of the old school and it saw only intermittent use as a Fringe location. It was finally sold for redevelopment in 2000 and was converted into flats, a change which at the very least preserved its fine Jacobean-style masonry for the future.

Davie Street School in 2021, estate agent’s photo from the sale of one of its flatsThe previous chapter in this series looked at Causewayside School. The following chapter covers Dean Public School.

If you have found this useful, informative or amusing, perhaps you would like to help contribute towards the running costs of this site – including keeping it ad-free and my book-buying budget to find further stories to bring you – by supporting me on ko-fi. Or please do just share this post on social media or amongst friends.

These threads © 2017-2025, Andy Arthur.

NO AI TRAINING: Any use of the contents of this website to “train” generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to generate text is expressly prohibited. The author reserves all rights to license uses of this work for generative AI training and development of machine learning language models.

The previous chapter of this series looked at Causewayside School.

If you have found this useful, informative or amusing, perhaps you would like to help contribute towards the running costs of this site – including keeping it ad-free and my book-buying budget to find further stories to bring you – by supporting me on ko-fi. Or please do just share this post on social media or amongst friends.

These threads © 2017-2025, Andy Arthur.

NO AI TRAINING: Any use of the contents of this website to “train” generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to generate text is expressly prohibited. The author reserves all rights to license uses of this work for generative AI training and development of machine learning language models.

#Edinburgh #EdinburghSchoolBoard #Education #Heriots #JamesClarkSchool #LostBoardSchoolsOfEdinburgh #Quaker #School #Schools #Theatre #Written2025