“We ceased to be the lunatic fringe. We’re now the lunatic core.”*…

Further, in a fashion, to yesterday’s post on analog computing, an essay from Benjamin Labatut (the author of two remarkable works of “scientific-historical fiction,” When We Cease to Understand the World and The MANIAC, continuing the animating theme of those books…

We will never know how many died during the Butlerian Jihad. Was it millions? Billions? Trillions, perhaps? It was a fantastic rage, a great revolt that spread like wildfire, consuming everything in its path, a chaos that engulfed generations in an orgy of destruction lasting almost a hundred years. A war with a death toll so high that it left a permanent scar on humanity’s soul. But we will never know the names of those who fought and died in it, or the immense suffering and destruction it caused, because the Butlerian Jihad, abominable and devastating as it was, never happened.

The Jihad was an imagined event, conjured up by Frank Herbert as part of the lore that animates his science-fiction saga Dune. It was humanity’s last stand against sentient technology, a crusade to overthrow the god of machine-logic and eradicate the conscious computers and robots that in the future had almost entirely enslaved us. Herbert described it as “a thalamic pause for all humankind,” an era of such violence run amok that it completely transformed the way society developed from then onward. But we know very little of what actually happened during the struggle itself, because in the original Dune series, Herbert gives us only the faintest outlines—hints, murmurs, and whispers, which carry the ghostly weight of prophecy. The Jihad reshaped civilization by outlawing artificial intelligence or any machine that simulated our minds, placing a damper on the worst excesses of technology. However, it was fought so many eons before the events portrayed in the novels that by the time they occur it has faded into legend and crystallized in apocrypha. The hard-won lessons of the catastrophe are preserved in popular wisdom and sayings: “Man may not be replaced.” “Once men turned their thinking over to machines in the hope that this would set them free. But that only permitted other men with machines to enslave them.” “We do not trust the unknown which can arise from imaginative technology.” “We must negate the machines-that-think.” The most enduring legacy of the Jihad was a profound change in humankind’s relationship to technology. Because the target of that great hunt, where we stalked and preyed upon the very artifacts we had created to lift ourselves above the seat that nature had intended for us, was not just mechanical intelligence but the machinelike attitude that had taken hold of our species: “Humans had set those machines to usurp our sense of beauty, our necessary selfdom out of which we make living judgments,” Herbert wrote.

Humans must set their own guidelines. This is not something machines can do. Reasoning depends upon programming, not on hardware, and we are the ultimate program!

The Butlerian Jihad removed a crutch—the part of ourselves that we had given over to technology—and forced human minds to develop above and beyond the limits of mechanistic reasoning, so that we would no longer depend on computers to do our thinking for us.

Herbert’s fantasy, his far-flung vision of a devastating war between humanity and the god of machine-logic, seemed quaint when he began writing it in the Sixties. Back then, computers were primitive by modern standards, massive mainframe contraptions that could process only hundreds of thousands of cycles per second (instead of billions, like today), had very little memory, operated via punch cards, and were not connected to one another. And we have easily ignored Herbert’s warnings ever since, but now the Butlerian Jihad has suddenly returned to plague us. The artificial-intelligence apocalypse is a new fear that keeps many up at night, a terror born of great advances that seem to suggest that, if we are not very careful, we may—with our own hands—bring forth a future where humanity has no place. This strange nightmare is a credible danger only because so many of our dreams are threatening to come true. It is the culmination of a long process that hearkens back to the origins of civilization itself, to the time when the world was filled with magic and dread, and the only way to guarantee our survival was to call down the power of the gods.

Apotheosis has always haunted the soul of humankind. Since ancient times we have suffered the longing to become gods and exceed the limits nature has placed on us. To achieve this, we built altars and performed rituals to ask for wisdom, blessings, and the means to reach beyond our capabilities. While we tend to believe that it is only now, in the modern world, that power and knowledge carry great risks, primitive knowledge was also dangerous, because in antiquity a part of our understanding of the world and ourselves did not come from us, but from the Other. From the gods, from spirits, from raging voices that spoke in silence.

[Labatut invokes the mysteries of the Vedas and their Altar of Fire, which was meant to develop “a mind, (that) when properly developed, could fly like a bird with outstretched wings and conquer the skies.”…]

Seen from afar by people who were not aware of what was being made, these men and women must surely have looked like bricklayers gone mad. And that same frantic folly seems to possess those who, in recent decades, have dedicated their hearts and minds to the building of a new mathematical construct, a soulless copy of certain aspects of our thinking that we have chosen to name “artificial intelligence,” a tool so formidable that, if we are to believe the most zealous among its devotees, will help us reach the heavens and become immortal…

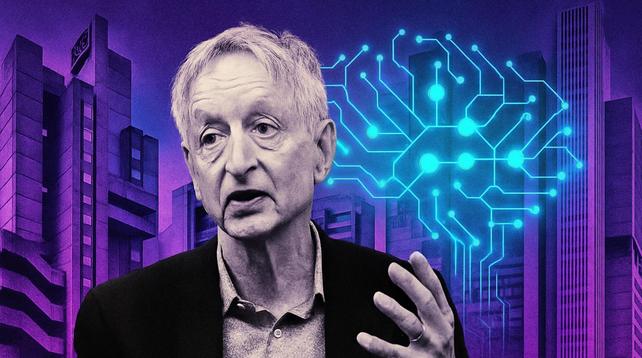

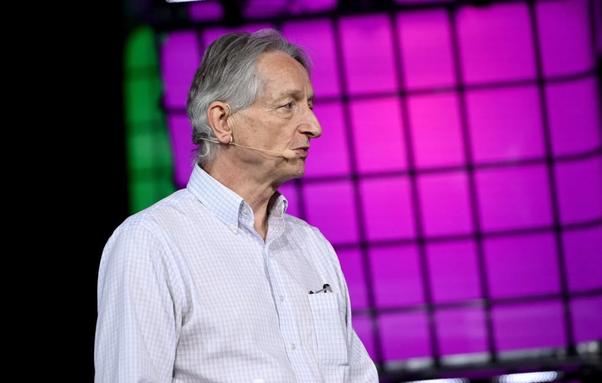

[Labatut recounts the stories– and works– of some of the creators of AI’s DNA: George Boole (and his logic), Claude Shannon (who put that logic to work), and Geoffrey Hinton (Boole’s great-great-grandson, and “the Godfather of AI,” who created of the first neural networks, but has more recently undergone a change of opinion)…]

… Hinton has been transformed. He has mutated from an evangelist of a new form of reason into a prophet of doom. He says that what changed his mind was the realization that we had, in fact, not replicated our intelligence, but created a superior one.

Or was it something else, perhaps? Did some unconscious part of him whisper that it was he, rather than his great-great-grandfather, who was intended by God to find the mechanisms of thought? Hinton does not believe in God, and he would surely deny his ancestor’s claim that pain is an instrument of the Lord’s will, since he was forced to have every one of his meals on his knees, resting on a pillow like a monk praying at the altar, because of a back injury that caused him excruciating pain. For more than seventeen years, he could not sit down, and only since 2022 has he managed to do so long enough to eat.

Hinton is adamant that the dangers of thinking machines are real. And not just short-term effects like job replacement, disinformation, or autonomous lethal weapons, but an existential risk that some discount as fantasy: that our place in the world might be supplanted by AI. Part of his fear is that he believes AI could actually achieve a sort of immortality, as the Vedic gods did. “The good news,” he has said, “is we figured out how to build things that are immortal. When a piece of hardware dies, they don’t die. If you’ve got the weights stored in some medium and you can find another piece of hardware that can run the same instructions, then you can bring it to life again. So, we’ve got immortality. But it’s not for us.”

Hinton seems to be afraid of what we might see when the embers of the Altar of Fire die down at the end of the sacrifice and the sharp coldness of the beings we have conjured up starts to seep into our bones. Are we really headed for obsolescence? Will humanity perish, not because of the way we treat all that surrounds us, nor due to some massive unthinking rock hurled at us by gravity, but as a consequence of our own irrational need to know all that can be known? The supposed AI apocalypse is different from the mushroom-cloud horror of nuclear war, and unlike the ravages of the wildfires, droughts, and inundations that are becoming commonplace, because it arises from things that we have, since the beginning of civilization, always considered positive and central to what makes us human: reason, intelligence, logic, and the capacity to solve the problems, puzzles, and evils that taint even the most fortunate person’s existence with everyday suffering. But in clawing our way to apotheosis, in daring to follow the footsteps of the Vedic gods who managed to escape from Death, we may shine a light on things that should remain in darkness. Because even if artificial intelligence never lives up to the grand and terrifying nightmare visions that presage a nonhuman world where algorithms hum along without us, we will still have to contend with the myriad effects this technology will have on human society, culture, and economics.

In the meantime, the larger specter of superintelligent AI looms over us. And while it is less likely and perhaps even impossible (nothing but a fairy tale, some say, a horror story intended to attract more money and investment by presenting a series of powerful systems not as the next step in our technological development but as a death-god that ends the world), it cannot be easily dispelled, for it reaches down and touches the fibers of our mythmaking apparatus, that part of our being that is atavistic and fearful, because it reminds us of a time when we shivered in caves and huddled together, while outside in the dark, with eyes that could see in the night, the many savage beasts and monsters of the past sniffed around for traces of our scent.

As every new AI model becomes stronger, as the voices of warning form a chorus, and even the most optimistic among us begin to fear this new technology, it is harder and harder to think without panic or to reason with logic. Thankfully, we have many other talents that don’t answer to reason. And we can always rise and take a step back from the void toward which we have so hurriedly thrown ourselves, by lending an ear to the strange voices that arise from our imagination, that feral territory that will always remain a necessary refuge and counterpoint to rationality.

Faced, as we are, with wild speculation, confronted with dangers that no one, however smart or well informed, is truly capable of managing or understanding, and taunted by the promises of unlimited potential, we may have to sound out the future not merely with science, politics, and reason, but with that devil-eye we use to see in the dark: fiction. Because we can find keys to doors we have yet to encounter in the worlds that authors have imagined in the past. As we grope forward in a daze, battered and bewildered by the capabilities of AI, we could do worse than to think about the desert planet where the protagonists of Herbert’s Dune novels sought to peer into the streaming sands of future time, under the heady spell of a drug called spice, to find the Golden Path, a way for human beings to break from tyranny and avoid extinction or stagnation by being more diverse, resilient, and free, evolving past purely logical reasoning and developing our minds and faculties to the point where our thoughts and actions are unpredictable and not bound by statistics. Herbert’s books, with their strange mixture of past and present, remind us that there are many ways in which we can continue forward while preserving our humanity. AI is here already, but what we choose to do with it and what limits we agree to place on its development remain decisions to be made. No matter how many billions of dollars are invested in the AI companies that promise to eliminate work, solve climate change, cure cancer, and rain down miracles unlike anything we have seen before, we can never fully give ourselves over to these mathematical creatures, these beings with no soul or sympathy, because they are neither alive nor conscious—at least not yet, and certainly not like us—so they do not share the contradictory nature of our minds.

In the coming years, as people armed with AI continue making the world faster, stranger, and more chaotic, we should do all we can to prevent these systems from giving more and more power to the few who can build them. But we should also consider a warning from Herbert, the central commandment he chose to enshrine at the heart of future humanity’s key religious text, a rule meant to keep us from becoming subservient to the products of our reason, and from bowing down before the God of Logic and his many fearsome offspring:

Thou shalt not make a machine in the likeness of a human mind…

Before and after artificial intelligence: “The Gods of Logic” in @Harpers. Eminently worth reading in full.

For a less pessimistic view, see: “A Journey Through the Uncanny Valley: Our Relational Futures with AI,” from @dylanhendricks at @iftf.

* Geoffrey Hinton

###

As we deliberate on Daedalus’ caution, we might we might send fantastically far-sighted birthday greetings to a tecno-optimist who might likely have brushed aside Labatut’s concerns: Hugo Gernsback, a Luxemborgian-American inventor, broadcast pioneer, writer, and publisher; he was born on this date in 1884.

Gernsback held 80 patents at the time of his death; he founded radio station WRNY, was involved in the first television broadcasts, and is considered a pioneer in amateur radio. But it was as a writer and publisher that he probably left his most lasting mark: In 1926, as owner/publisher of the magazine Modern Electrics, he filled a blank spot in his publication by dashing off the first chapter of a series called “Ralph 124C 41+.” The twelve installments of “Ralph” were filled with inventions unknown in 1926, including “television” (Gernsback is credited with introducing the word), fluorescent lighting, juke boxes, solar energy, television, microfilm, vending machines, and the device we now call radar.

The “Ralph” series was an astounding success with readers; and later that year Gernsback founded the first magazine devoted to science fiction, Amazing Stories. Believing that the perfect sci-fi story is “75 percent literature interwoven with 25 percent science,” he coined the term “science fiction.”

Gernsback was a “careful” businessman, who was tight with the fees that he paid his writers– so tight that H. P. Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith referred to him as “Hugo the Rat.”

Still, his contributions to the genre as publisher were so significant that, along with H.G. Wells and Jules Verne, he is sometimes called “The Father of Science Fiction”; in his honor, the annual Science Fiction Achievement awards are called the “Hugos.”

(Coincidentally, today is also the birthday– in 1906– of Philo T. Farnsworth, the man who actually did invent television.)

Gernsback, wearing one of his inventions, TV Glasses

source

#ai #artificialIntelligence #broadcasting #claudeShannon #computing #consciousness #culture #extinction #geoffreyHinton #georgeBoole #history #hugoGernsback #invention #mind #philoFarnsworth #philosophy #radio #religion #science #scienceFiction #technology #television