The Agile Manifesto: Rearranging Deck Chairs While Five Dragons Burn Everything Down

The Agile Manifesto: Rearranging Deck Chairs While Five Dragons Burn Everything Down

Why the ‘Sound’ Principles Miss the Dragons That Actually Kill Software Projects

The Agile Manifesto isn’t wrong, per se—it’s addressing the wrong problems entirely. And that makes it tragically inadequate.

For over two decades, ‘progressive’ software teams have been meticulously implementing sprints, standups, and retrospectives whilst the real dragons have been systematically destroying their organisations from within. The manifesto’s principles aren’t incorrect; they’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic whilst it sinks around them.

The four values and twelve principles address surface symptoms of dysfunction whilst completely ignoring the deep systemic diseases that kill software projects. It’s treating a patient’s cough whilst missing the lung cancer—technically sound advice that’s spectacularly missing the point.

The Real Dragons: What Actually Destroys Software Teams

Whilst we’ve been optimising sprint ceremonies and customer feedback loops, five ancient dragons have been spectacularly burning down software development and tech business effectiveness:

Dragon #1: Human Motivation Death Spiral

Dragon #2: Dysfunctional Relationships That Poison Everything

Dragon #3: Shared Delusions and Toxic Assumptions

Dragon #4: The Management Conundrum—Questioning the Entire Edifice

Dragon #5: Opinioneering—The Ethics of Belief Violated

These aren’t process problems or communication hiccups. They’re existential threats that turn the most well-intentioned agile practices into elaborate theatre whilst real work grinds to a halt. And the manifesto? It tiptoes around these dragons like they don’t exist.

Dragon #1: The Motivation Apocalypse

‘Individuals and interactions over processes and tools’ sounds inspiring until you realise that your individuals are fundamentally unmotivated to do good work. The manifesto assumes that people care—but what happens when they don’t?

The real productivity killer isn’t bad processes; it’s developers who have mentally checked out because:

- They’re working on problems they find meaningless

- Their contributions are invisible or undervalued

- They have no autonomy over how they solve problems

- The work provides no sense of mastery or purpose

- They’re trapped in roles that don’t match their strengths

You can have the most collaborative, customer-focused, change-responsive team in the world, but if your developers are quietly doing the minimum to avoid getting fired, your velocity will crater regardless of your methodology.

The manifesto talks about valuing individuals but offers zero framework for understanding what actually motivates people to do their best work. It’s having a sports philosophy that emphasises teamwork whilst ignoring whether the players actually want to win the game. How do you optimise ‘individuals and interactions’ when your people have checked out?

Dragon #2: Relationship Toxicity That Spreads Like Cancer

‘Customer collaboration over contract negotiation’ assumes that collaboration is even possible—but what happens when your team relationships are fundamentally dysfunctional?

The real collaboration killers that the manifesto ignores entirely:

- Trust deficits: When team members assume bad faith in every interaction

- Ego warfare: When technical discussions become personal attacks on competence

- Passive aggression: When surface civility masks deep resentment and sabotage

- Fear: When people are afraid to admit mistakes or ask questions

- Status games: When helping others succeed feels like personal failure

You hold all the retrospectives you want, but if your team dynamics are toxic, every agile practice becomes a new battlefield. Sprint planning turns into blame assignment. Code reviews become character assassination. Customer feedback becomes ammunition for internal warfare.

The manifesto’s collaboration principles are useless when the fundamental relationships are broken. It’s having marriage counselling techniques for couples who actively hate each other—technically correct advice that misses the deeper poison. How do you collaborate when trust has been destroyed? What good are retrospectives when people are actively sabotaging each other?

Dragon #3: Shared Delusions That Doom Everything

‘Working software over comprehensive documentation’ sounds pragmatic until you realise your team is operating under completely different assumptions about what ‘working’ means, what the software does, and how success is measured. But what happens when your team shares fundamental delusions about reality?

The productivity apocalypse happens when teams share fundamental delusions:

- Reality distortion: Believing their product is simpler/better/faster than it actually is

- Capability myths: Assuming they can deliver impossible timelines with current resources

- Quality blindness: Thinking ‘works on my machine’ equals production-ready

- User fiction: Building for imaginary users with imaginary needs

- Technical debt denial: Pretending that cutting corners won’t compound into disaster

These aren’t communication problems that better customer collaboration can solve—they’re shared cognitive failures that make all collaboration worse. When your entire team believes something that’s factually wrong, more interaction just spreads the delusion faster.

The manifesto assumes that teams accurately assess their situation and respond appropriately. But when their shared mental models are fundamentally broken? All the adaptive planning in the world won’t help if you’re adapting based on fiction.

Dragon #4: The Management Conundrum—Why the Entire Edifice Is Suspect

‘Responding to change over following a plan’ sounds flexible, but let’s ask the deeper question: Why do we have management at all?

The manifesto takes management as a given and tries to optimise around it. But what if the entire concept of management—people whose job is to direct other people’s work without doing the work themselves—is a fundamental problem?

Consider what management actually does in most software organisations:

- Creates artificial hierarchies that slow down decision-making

- Adds communication layers that distort information as it flows up and down

- Optimises for command and control rather than effectiveness

- Makes decisions based on PowerPoint and opinion rather than evidence

- Treats humans like interchangeable resources to be allocated and reallocated

The devastating realisation is that management in software development is pure overhead that actively impedes the work. Managers who:

- Haven’t written code in years (or ever) making technical decisions

- Set timelines based on business commitments rather than reality

- Reorganise teams mid-project because a consultant recommended ‘matrix management’ or some such

- Measure productivity by story points rather than needs attended to (or met)

- Translate clear customer needs into incomprehensible requirements documents

What value does this actually add? Why do we have people who don’t understand the work making decisions about the work? What if every management layer is just expensive interference?

The right number of managers for software teams is zero. The entire edifice of management—the org charts, the performance reviews, the resource allocation meetings—is elaborate theatre that gets in the way of people solving problems.

Productive software teams operate more like research labs or craftsman guilds: self-organising groups of experts who coordinate directly with each other and with the people who use their work. No sprint masters, no product owners, no engineering managers—just competent people working together to solve problems.

The manifesto’s principles assume management exists and try to make it less harmful. But they never question whether it has any value at all.

Dragon #5: Opinioneering—The Ethics of Belief Violated

Here’s the dragon that the manifesto not only ignores but actually enables: the epidemic of strong opinions held without sufficient evidence.

William Kingdon Clifford wrote in 1877 that

‘it is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence’

(Clifford, 1877).

In software development, we’ve created an entire culture that violates this ethical principle daily through systematic opinioneering:

Technical Opinioneering: Teams adopting microservices because they’re trendy, not because they solve actual problems. Choosing React over Vue because it ‘feels’ better. Implementing event sourcing because it sounds sophisticated. Strong architectural opinions based on blog posts rather than deep experience with the trade-offs.

Process Opinioneering: Cargo cult agile practices copied from other companies without understanding why they worked there. Daily standups that serve no purpose except ‘that’s what agile teams do.’ Retrospectives that generate the same insights every sprint because the team has strong opinions about process improvement but no evidence about what actually works.

Business Opinioneering: Product decisions based on what the CEO likes rather than what users require. Feature priorities set by whoever argues most passionately rather than data about user behaviour. Strategic technology choices based on industry buzz rather than careful analysis of alternatives.

Cultural Opinioneering: Beliefs about remote work, hiring practices, team structure, and development methodologies based on what sounds right rather than careful observation of results.

The manifesto makes this worse by promoting ‘individuals and interactions over processes and tools’ without any framework for distinguishing between evidence-based insights and opinion-based groupthink. It encourages teams to trust their collective judgement without asking whether that judgement is grounded in sufficient evidence. But what happens when the collective judgement is confidently wrong? How do you distinguish expertise from persuasive ignorance?

When opinioneering dominates, you get teams that are very confident about practices that don’t work, technologies that aren’t suitable, and processes that waste enormous amounts of time. Everyone feels like they’re making thoughtful decisions, but they’re sharing unfounded beliefs dressed up as expertise.

The Deeper Problem: Dysfunctional Shared Assumptions and Beliefs

The five dragons aren’t just symptoms—they’re manifestations of something deeper. Software development organisations operate under shared assumptions and beliefs that make effectiveness impossible, and the Agile Manifesto doesn’t even acknowledge this fundamental layer exists.

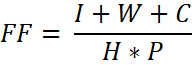

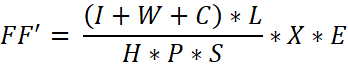

My work in Quintessence provides the missing framework for understanding why agile practices fail so consistently. The core insight is that organisational effectiveness is fundamentally a function of collective mindset:

Organisational effectiveness = f(collective mindset)

I demonstrate that every organisation operates within a “memeplex“—a set of interlocking assumptions and beliefs about work, people, and how organisations function. These beliefs reinforce each other so strongly that changing one belief causes the others to tighten their grip to preserve the whole memeplex.

This explains why agile transformations consistently fail. Teams implement new ceremonies whilst maintaining the underlying assumptions that created their problems in the first place. They adopt standups and retrospectives whilst still believing people are motivated, relationships are authentic, management adds value, and software is always the solution.

Consider the dysfunctional assumptions that pervade conventional software development:

About People: Most organisations and their management operate under “Theory X” assumptions—people are naturally lazy, require external motivation, need oversight to be productive, and will shirk responsibility without means to enforce accountability. These beliefs create the very motivation problems they claim to address.

About Relationships: Conventional thinking treats relationships as transactional. Competition drives performance. Hierarchy creates order. Control prevents chaos. Personal connections are “unprofessional.” These assumptions poison the collaboration that agile practices supposedly enable.

About Work: Software is the solution to every problem. Activity indicates value. Utilisation (of eg workers) drives productivity. Efficiency trumps effectiveness. Busyness proves contribution. These beliefs create the delusions that make teams confidently ineffective.

About Management: Complex work requires coordination. Coordination requires hierarchy. Hierarchy requires managers. Managers add value through oversight and direction. These assumptions create the parasitic layers that impede the very work they claim to optimise.

About Knowledge: Strong opinions indicate expertise. Confidence signals competence. Popular practices are best practices. Best practices are desirable. Industry trends predict future success. These beliefs create the opinioneering that replaces evidence with folklore.

Quintessence (Marshall, 2021) shows how “quintessential organisations” operate under completely different assumptions:

- People find joy in meaningful work and naturally collaborate when conditions support it

- Relationships based on mutual care and shared purpose are the foundation of effectiveness

- Work is play when aligned with purpose and human flourishing

- Management is unnecessary parasitism—people doing the work make the decisions about the work

- Beliefs must be proportioned to evidence and grounded in serving real human needs

The Agile Manifesto can’t solve problems created by fundamental belief systems because it doesn’t even acknowledge these belief systems exist. It treats symptoms whilst leaving the disease untouched. Teams optimise ceremonies whilst operating under assumptions that guarantee continued dysfunction.

This is why the Qunitessence approach differs so radically from ‘Agile’ approaches. Instead of implementing new practices, quintessential organisations examine their collective assumptions and beliefs. Instead of optimising processes, they transform their collective mindset. Instead of rearranging deck chairs, they address the fundamental reasons the ship is sinking.

The Manifesto’s Tragic Blindness

Here’s what makes the Agile Manifesto so inadequate: it assumes the Five Dragons don’t exist. It offers principles for teams that are motivated, functional, reality-based, self-managing, and evidence-driven—but most software teams are none of these things.

The manifesto treats symptoms whilst ignoring diseases:

- It optimises collaboration without addressing what makes collaboration impossible

- It values individuals without confronting what demotivates them

- It promotes adaptation without recognising what prevents teams from seeing their shared assumptions and beliefs clearly

- It assumes management adds value rather than questioning whether management has any value at all

- It encourages collective decision-making without any framework for leveraging evidence-based beliefs

This isn’t a failure of execution—it’s a failure of diagnosis. The manifesto identified the wrong problems and thus prescribed the wrong solutions.

Tom Gilb’s Devastating Assessment: The Manifesto Is Fundamentally Fuzzy

Software engineering pioneer Tom Gilb delivers the most damning critique of the Agile Manifesto: its principles are

‘so fuzzy that I am sure no two people, and no two manifesto signers, understand any one of them identically’

(Gilb, 2005).

This fuzziness isn’t accidental—it’s structural. The manifesto was created by ‘far too many “coders at heart” who negotiated the Manifesto’ without

‘understanding of the notion of delivering measurable and useful stakeholder value’

(Gilb, 2005).

The result is a manifesto that sounds profound but provides no actionable guidance for success in product development.

Gilb’s critique exposes the manifesto’s fundamental flaw: it optimises for developer comfort rather than stakeholder value. The principles read like a programmer’s wish list—less documentation, more flexibility, fewer constraints—rather than a framework for delivering measurable results to people who actually need the software.

This explains why teams can religiously follow agile practices whilst consistently failing to deliver against folks’ needs. The manifesto’s principles are so vague that any team can claim to be following them whilst doing whatever they want. ‘Working software over comprehensive documentation’ means anything you want it to mean. ‘Responding to change over following a plan’ provides zero guidance on how to respond or what changes matter. (Cf. Quantification)

How do you measure success when the principles themselves are unmeasurable? What happens when everyone can be ‘agile’ whilst accomplishing nothing? How do you argue against a methodology that can’t be proven wrong?

The manifesto’s fuzziness enables the very dragons it claims to solve. Opinioneering thrives when principles are too vague to be proven wrong. Management parasitism flourishes when success metrics are unquantified Shared delusions multiply when ‘working software’ has no operational definition.

Gilb’s assessment reveals why the manifesto has persisted despite its irrelevance: it’s comfortable nonsense that threatens no one and demands nothing specific. Teams can feel enlightened whilst accomplishing nothing meaningful for stakeholders.

Stakeholder Value vs. All the Needs of All the Folks That Matter™

Gilb’s critique centres on ‘delivering measurable and useful stakeholder value’—but this phrase itself illuminates a deeper problem with how we think about software development success. ‘Stakeholder value’ sounds corporate and abstract, like something you’d find in a business school textbook or an MBA course (MBA – maybe best avoided – Mintzberg)

What we’re really talking about is simpler, less corporate and more human: serving all the needs of all the Folks That Matter™.

The Folks That Matter aren’t abstract ‘stakeholders’—they’re real people trying to get real things done:

- The nurse trying to access patient records during a medical emergency

- The small business owner trying to process payroll before Friday

- The student trying to submit an assignment before the deadline

- The elderly person trying to video call their grandchildren

- The developer trying to understand why the build is broken again

When software fails these people, it doesn’t matter how perfectly agile your process was. When the nurse can’t access records, your retrospectives are irrelevant. When the payroll system crashes, your customer collaboration techniques are meaningless. When the build and smoke takes 30+ minutes, your adaptive planning is useless.

The Agile Manifesto’s developer-centric worldview treats these people as distant abstractions—’users’ and ‘customers’ and ‘stakeholders.’ But they’re not abstractions. They’re the Folks That Matter™, and their needs are the only reason software development exists.

The manifesto’s principles consistently prioritise developer preferences over the requirements of the Folks That Matter™. ‘Working software over comprehensive documentation’ sounds reasonable until the Folks That Matter™ require understanding of how to use the software. ‘Individuals and interactions over processes and tools’ sounds collaborative until the Folks That Matter™ require consistent, reliable results from those interactions.

This isn’t about being anti-developer—it’s about recognising that serving the Folks That Matter™ is the entire point. The manifesto has it backwards: instead of asking ‘How do we make development more comfortable for developers?’ we might ask ‘How do we reliably serve all the requirements of all the Folks That Matter™?’ That question changes everything. It makes motivation obvious—you’re solving real problems for real people. It makes relationship health essential—toxic teams can’t serve others effectively. It makes reality contact mandatory—delusions about quality hurt real people. It makes evidence-based decisions critical—opinions don’t serve the Folks That Matter™; results do.

Most importantly, it makes management’s value proposition clear: Do you help us serve the Folks That Matter™ better, or do you get in the way? If the answer is ‘get in the way,’ then management becomes obviously a dysfunction.

What Actually Addresses the Dragons

If we want to improve software development effectiveness, we address the real dragons:

Address Motivation: Create work that people actually care about. Give developers autonomy, mastery, and purpose. Match people to problems they find meaningful. Make contributions visible and valued.

Heal Toxic Relationships: Build psychological safety where people can be vulnerable about mistakes. Address ego and status games directly. Create systems where helping others succeed feels like personal victory.

Resolve Shared Delusions: Implement feedback loops that invite contact with reality. Measure what actually matters. Create cultures where surfacing uncomfortable truths is rewarded rather than punished.

Transform Management Entirely: Experiment with self-organising teams. Distribute decision-making authority to where expertise actually lives. Eliminate layers between problems and problem-solvers. Measure needs met, not management theatre.

Counter Evidence-Free Beliefs: Institute a culture where strong opinions require strong evidence. Enable and encourage teams to articulate the assumptions behind their practices. Reward changing your mind based on new data. Excise confident ignorance.

These aren’t process improvements or methodology tweaks—they’re organisational transformation efforts that require fundamentally different approaches than the manifesto suggests.

Beyond Agile: Addressing the Real Problems

The future of software development effectiveness isn’t in better sprint planning or more customer feedback. It’s in organisational structures that:

- Align individual motivation with real needs

- Create relationships based on trust

- Enable contact with reality at every level

- Eliminate management as dysfunctional

- Ground all beliefs in sufficient evidence

These are the 10x improvements hiding in plain sight—not in our next retrospective, but in our next conversation about why people don’t care about their work. Not in our customer collaboration techniques, but in questioning whether we have managers at all. Not in our planning processes, but in demanding evidence for every strong opinion.

Conclusion: The Problems We Were Addressing All Along

The Agile Manifesto succeeded in solving the surface developer bugbears of 2001: heavyweight processes and excessive documentation. But it completely missed the deeper organisational and human issues that determine whether software development succeeds or fails.

The manifesto’s principles aren’t wrong—they’re just irrelevant to the real challenges. Whilst we’ve been perfecting our agile practices, the dragons of motivation, relationships, shared delusions, management being dysfunctional, and opinioneering have been systematically destroying software development from within.

Is it time to stop optimising team ceremonies and start addressing the real problems? Creating organisations where people are motivated to do great work, relationships enable rather than sabotage collaboration, shared assumptions are grounded in reality, traditional management no longer exists, and beliefs are proportioned to evidence.

But ask yourself: Does your organisation address any of these fundamental issues? Are you optimising ceremonies whilst your dragons run wild? What would happen if you stopped rearranging deck chairs and started questioning why people don’t care about their work?

Because no amount of process optimisation will save a team where people don’t care, can’t trust each other, believe comfortable lies, are managed by people who add negative value, and make decisions based on opinions rather than evidence.

The dragons are real, and they’re winning. Are we finally ready to address them?

Further Reading

Beck, K., Beedle, M., van Bennekum, A., Cockburn, A., Cunningham, W., Fowler, M., … & Thomas, D. (2001). Manifesto for Agile Software Development. Retrieved from https://agilemanifesto.org/

Clifford, W. K. (1877). The ethics of belief. Contemporary Review, 29, 289-309.

Gilb, T. (2005). Competitive Engineering: A Handbook for Systems Engineering, Requirements Engineering, and Software Engineering Using Planguage. Butterworth-Heinemann.

Gilb, T. (2017). How well does the Agile Manifesto align with principles that lead to success in product development? Retrieved from https://www.gilb.com/blog/how-well-does-the-agile-manifesto-align-with-principles-that-lead-to-success-in-product-development

Marshall, R.W. (2021). *Quintessence: An Acme for Software Development Organisations. *[online] leanpub.com. Falling Blossoms (LeanPub). Available at: https://leanpub.com/quintessence/ [Accessed 15 Jun 2022].

#1 #2 #3 #4 #5