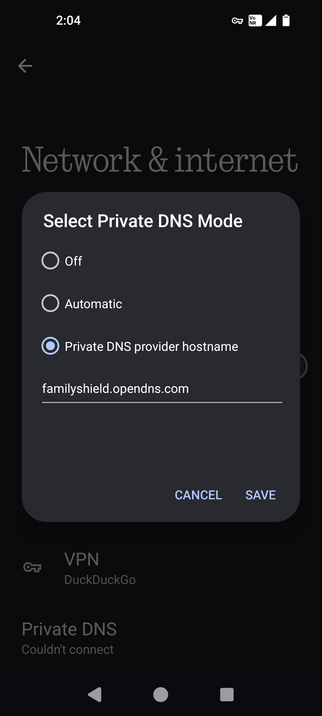

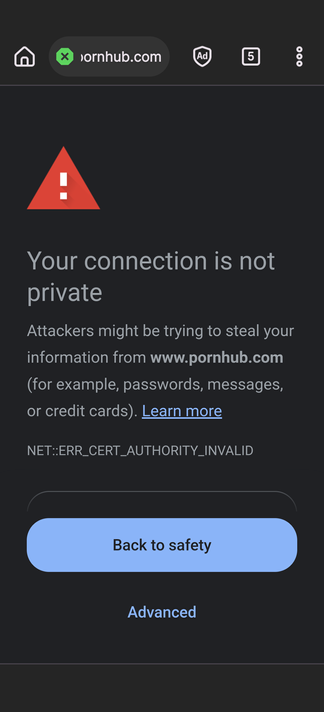

If you need a porn filter throughout your Smartphone, changing the default DNS provider helps. For that, go to Settings->Network & Internet->Private DNS->Private DNS provider hostname->type-familyshield.opendns.com-> Save

#pornrecovery #sexaddiction

God speed your porn recovery!

Conversation with Professor Justin Lehmiller on Sexology and Human Sexuality

Scott Douglas Jacobsen

In-Sight Publishing, Fort Langley, British Columbia, Canada

Correspondence: Scott Douglas Jacobsen (Email: scott.jacobsen2025@gmail.com)

Received: November 4, 2024

Accepted: N/A

Published: January 22, 2025

Abstract

This interview presents an in-depth conversation between Scott Douglas Jacobsen and Dr. Justin J. Lehmiller, a renowned social psychologist and Research Fellow at The Kinsey Institute. Dr. Lehmiller discusses his extensive research on human sexuality, including sexual fantasies, casual sex, consensual non-monogamy, and sexual health. The dialogue explores the evolution of sex education, highlighting the disparities in North American educational frameworks and contrasting them with progressive models like the Netherlands’ “Long Live Love” program. Dr. Lehmiller addresses common misconceptions about sexual behaviors and disorders, such as porn addiction and sex addiction, emphasizing the importance of scientific scrutiny over societal stereotypes. Additionally, the interview delves into the impact of social media on self-perception and sexual health, the challenges and dynamics of consensual non-monogamous relationships, and the ongoing stigmatization of sex research. The conversation underscores the necessity for comprehensive, evidence-based approaches to sexuality education and research to foster healthier and more informed societal attitudes toward human sexuality.

Keywords: Consensual Non-Monogamy, Human Sexuality, Long Live Love Program, Porn Addiction, Sex Addiction, Sex Education, Sexual Fantasies, Sexual Health, Sexual Psychology, Social Media Impact

Introduction

In this insightful interview conducted on January 20, 2025, Scott Douglas Jacobsen engages in a comprehensive discussion with Dr. Justin J. Lehmiller, a distinguished social psychologist and Research Fellow at The Kinsey Institute. Dr. Lehmiller is internationally recognized for his expertise in human sexuality, having authored influential textbooks and popular works such as “Tell Me What You Want” and “The Psychology of Human Sexuality.” His research encompasses a broad spectrum of topics, including sexual fantasies, casual sex, consensual non-monogamy, and sexual health, with publications featured in prominent outlets like Playboy, VICE, and USA Today. The conversation begins with Dr. Lehmiller’s personal journey into the field of sexuality research, highlighting his academic background and the pivotal moment that directed his focus toward integrating sexuality into the study of romantic relationships. The interview progresses to examine prevailing misconceptions about human sexuality, emphasizing the importance of scientific inquiry in debunking societal myths such as the incomplete understanding of the clitoris and the oversimplified notion that “opposites attract.” A significant portion of the dialogue addresses generational differences in sexual behaviors and relationship preferences, noting trends such as reduced sexual activity among younger adults juxtaposed with an increase in kinkier sexual practices. Dr. Lehmiller also explores the complexities of consensual non-monogamous relationships, discussing the challenges of navigating jealousy and societal stigma despite growing cultural acceptance and media representation. The interview further critiques the current state of sex education in North America, contrasting it with the Netherlands’ comprehensive “Long Live Love” program. Dr. Lehmiller advocates for age-appropriate, scientifically accurate sex education that evolves with developmental stages, arguing that such approaches are crucial for fostering healthy sexual attitudes and behaviors. Finally, the conversation delves into the role of social media in shaping perceptions of sexuality, the misconceptions surrounding sex and porn addiction, and the enduring stigmatization of sex research. Dr. Lehmiller emphasizes the need for evidence-based frameworks and increased funding to advance the understanding of human sexuality beyond prevailing negative narratives. This interview provides valuable insights into the multifaceted nature of human sexuality, the importance of robust sex education, and the ongoing challenges faced by researchers in the field. Dr. Lehmiller’s expertise offers a nuanced perspective on fostering healthier societal attitudes toward sexuality through informed research and comprehensive educational strategies.

Main Text (Interview)

Interviewer: Scott Douglas Jacobsen

Interviewee: Prof. Justin Lehmiller

Section 1: Personal Journey into Sexuality Research

Scott Douglas Jacobsen: Today, we are here with Dr. Justin Lehmiller. He is a social psychologist and research fellow at the Kinsey Institute at Indiana University. His work focuses on human sexuality, including sexual fantasies, casual sex, consensual non-monogamy, and sexual health. He is the author of Tell Me What You Want and The Psychology of Human Sexuality, a widely used textbook. Today, we’re going to discuss your expertise specifically. As a quick background question, what was the first clue that this topic would become an intriguing research area for you to pursue professionally in the long term?

Prof. Justin Lehmiller: Well, sexuality was not something I initially considered for my career until I was already in graduate school working on my PhD in social psychology. I went to Purdue University to study the psychology of romantic relationships. While there, I was assigned to teach a human sexuality course.

That was my first exposure to the world of sex research. I attended Catholic schools for much of my life, including middle school, my undergraduate studies, and my master’s program. Sex wasn’t a common topic of discussion in those environments, and I hadn’t taken any formal courses on it.

It wasn’t until I was assigned as a teaching assistant that I realized sexuality is an area scientists actively study. I learned how important it is and realized that here I was, studying to be a social psychologist focusing on romantic relationships, and nobody was talking about sex, which seemed strange. My goal became integrating sexuality research into my relationship research, and that has been the focus of my work ever since.

Over the years, my research has expanded to cover many different aspects of sexuality because there are many fascinating and vital questions in this field.

Section 2: Surprising Aspects of Human Sexuality

Jacobsen: What are some of the most surprising aspects of human sexuality—things that we think we know but, as laypeople, do not?

Lehmiller: There are many things we assume about sex that often don’t hold up under scientific scrutiny. For example, research on the clitoris revealed something surprising: it wasn’t until about 20 years ago that we finally mapped out the entire structure of this organ in the body. This is just one example of how much of what we think we know or take for granted about human sexuality can be incomplete or incorrect until it is examined scientifically.

Another example is the popular belief that “opposites attract.” While there is some truth to the idea that having a partner with some differences can be exciting, research shows that most people prefer similar partners. Shared values foster a sense of safety, understanding, and acceptance. When discussing conventional beliefs like “opposites attract,” the reality is often more complex once we delve into the research.

Section 3: Generational Differences in Sexual Behaviors and Relationship Preferences

Jacobsen: Demographers also tend to analyze different generational cohorts, such as Gen Z, millennials, boomers, and Gen X, to better understand these dynamics. What are some of the differences you find in those cohorts, demographically, in terms of their sexual behaviours and relationship preferences?

Lehmiller: There are many differences across generations, and one of them is that there are differences in sexual activity levels. For example, younger adults are less sexually active today compared to previous generations. They are having less sex with fewer partners. However, the type of sex they are engaging in tends to be kinkier compared to generations past.

So, less sex but more kink for younger adults. Another aspect I’ve looked at in my work is how sexual fantasies differ at different stages of life. This is an area that had not been previously explored because most published studies on sexual fantasies are based on college students and young adults. These samples might not necessarily represent the broader population when it comes to what we fantasize about or think about regarding sex.

One of the findings is that younger adults, in addition to having more kinky fantasies than older adults, also have more fantasies about romance, passion, and connection. By contrast, when examining midlife adults, they tend to have more fantasies involving sex with multiple partners, novelty and excitement, and taboo activities. This reflects the developmental time course of sexual fantasies, where they evolve and adapt over time to meet specific needs during different life stages.

Many younger adults, especially those today, have not had significant relationship experiences yet. Young adults are living in an era of delayed adulthood, where traditional milestones are being pushed back, such as waiting longer to have sex for the first time, entering serious, committed relationships, or getting married. This is reflected in their fantasies, which often focus more on passion, romance, intimacy, and connection.

Older adults, many of whom have been in long-term monogamous relationships for extended periods, often feel a need to break out of their routines and explore something new and different. We know that people tend to grow bored with sexual routines, so exploring sexuality and relationships at various phases of life or through different generational lenses is valuable. Sexuality constantly evolves and changes throughout our lives.

Section 4: Gender Differences in Sexual Fantasies

Jacobsen: What are some of the noteworthy similarities and differences, gender-wise, in terms of sex or sexual fantasies?

Lehmiller: In terms of sexual fantasies and sexual preferences, I would preface this by saying there are many differences across genders, but there are also numerous similarities. Ultimately, we are more similar than different when looking at the content of sexual fantasies. Most of the things men fantasize about, women also fantasize about, and vice versa. However, some key differences do exist.

For instance, men are more likely than women to frequently fantasize about sex with multiple partners or engage in taboo or forbidden activities—things they are not supposed to do.

By contrast, women, compared to men, have more fantasies about passion, romance, and intimacy—fantasies that meet deeper needs for emotional connection. However, women also report more fantasies involving kink and BDSM than men do. It’s important to note that men also fantasize about passion and romance; most have done so at some point.

Most men have also fantasized about kink, just as most women have fantasized about multiple partners and taboo activities. But when looking at the frequency of these fantasies, significant differences emerge across genders.

Section 5: Lifespan Changes in Sexuality

Jacobsen: What about across the arc of the lifespan? How do people adapt to physiological changes, energy levels, and shifts in their self-perception and sexuality over time? What are some of the changes that occur over that arc you mentioned earlier?

Lehmiller: Sexuality changes in many ways as we age. Starting with physiological or physical changes, we know that as people get older, they are more likely to develop chronic health conditions, sexual dysfunctions, and other difficulties. That’s not to say that young adults can’t experience these issues—many do—but overall health status typically changes as we age, which can impact our sex lives.

For instance, chronic illnesses or certain disabilities can make specific sexual activities more challenging, less comfortable, or less pleasurable. They can also lead to changes in sexual function. For example, someone with cardiovascular issues might encounter arousal problems, such as erectile difficulties or issues with vaginal lubrication.

In addition, for women, menopause and the subsequent abrupt reduction in sex hormone production can significantly affect sexual functioning and pleasure. So, there are numerous physical changes over time that we need to adapt to. Unfortunately, the only sex education most of us receive, if we’re lucky enough to get any, occurs during adolescence. In reality, we need sex education tailored to our current stage of life. Hence, we understand how our bodies are functioning at that time. But it’s not just the physical changes we experience.

Psychologically, our desires and needs also evolve. For example, when looking at sexuality among older adults, one key factor in maintaining sexual satisfaction is having a flexible definition of sex that evolves. Seniors who maintain a strict definition of sex as solely penetration often experience more declines in sexual satisfaction. By contrast, older adults who adopt a broader view of sex—seeing it as a form of intimacy that includes a range of activities—tend to experience fewer decreases in satisfaction and, in some cases, report increases.

So, to maintain sexual satisfaction as we age, we need to adapt both physically and psychologically, changing the way we approach and think about sex.

Then, of course, on top of all of this, we also experience changes in our relationships over time. These changes can create certain sexual issues and difficulties as well. I like to think of sex as a biopsychosocial phenomenon. You have the biological and physiological factors that impact our sexuality, the psychological factors such as personality traits and characteristics, and the social and environmental factors, including our relationships and cultural context. All these elements interact and influence our sexuality.

To talk about maintaining sexual health and satisfaction, we need to consider all of these factors. We can’t focus solely on one aspect; we need to look at them within this interconnected, broader context.

Section 6: Impact of Social Media on Sexuality

Jacobsen: One major change in recent years has been the rise of social media and communication technologies. How do these impact people’s self-perception, conceptions of healthy sexuality, and overall experiences? Are these significant factors or just pervasive without much impact?

Lehmiller: As part of the biopsychosocial model I mentioned, social media falls into the social category. It is indeed a significant factor that can influence our sexuality. One way social media impacts us is that many people use it to learn and find answers to their questions. Traditional sex education often doesn’t cover everything people need to know, so more and more individuals turn to the internet and social media to fill those gaps.

On social media, numerous influencers and content creators post about sex and relationships regularly. As a sex educator, I try to post educational, science-based content that provides responsible and hopefully helpful information. However, there is also much misinformation circulating online. People sometimes post content not backed by science, leading to widespread misconceptions.

A good example of this is the annual online challenge called “No Nut November,” where men encourage each other to abstain from masturbation, porn, sex, and orgasm for the entire month. The stated goal of this challenge is often to boost testosterone. There’s a popular notion on social media that men should practice semen retention to increase testosterone and enhance vitality.

And the reality is that no science or data supports those claims. This is where social media can become dangerous as a source for learning about sex because so much of the information available is not scientifically based. People must be cautious about whom they follow and what content they engage with online. Before making significant changes to your sex life or intimate life, you should vet the information to ensure its credibility and accuracy. That’s one-way social media can impact our sexuality—by shaping what we learn and think about it.

But there are many other ways as well. Increasingly, social media is influencing our dating lives. People often post details of their dates online, sometimes leading to what I would call “performative dating,” where the focus shifts to doing things for followers, likes, and comments rather than cultivating authentic human connections. This can create distorted views of what healthy sexual and romantic relationships look like because we’re exposed to a curated, selectively edited version of reality. This selective presentation raises our comparison standards and can make us feel inadequate as if we’re not measuring up to others who seem to have perfect dates and relationships. We must see the conflicts, difficulties, and challenges behind the scenes.

So, yes, there are many ways in which social media can influence our sex lives and relationships.

Section 7: Claims about Porn Addiction and Sex Addiction

Jacobsen: Many people have heard claims about disorders such as porn addiction or sex addiction. Is there any data that supports these claims?

Lehmiller: Sex and porn addiction are frequently discussed topics on social media, often surrounded by misinformation. First and foremost, there is no formal clinical diagnosis of sex addiction or porn addiction. If you look in the DSM, the “psychiatry Bible,” you won’t find these conditions listed. These are contentious concepts within the field of sex therapy and, more broadly, in psychology and psychiatry.

My view, after extensively reviewing the literature, is that some people do struggle to regulate their sexual behaviour or porn use and may experience negative impacts. However, this is relatively uncommon. It’s not as pervasive as popular media might suggest. Most people, when surveyed, report that pornography has no negative effects on them, or even positive effects.

For the minority who do experience negative impacts from porn use, the data often points to moral conflicts as the primary cause. They may engage in behaviours like watching porn or masturbating but feel that these actions go against their moral or personal values. This creates a state of dissonance—an uncomfortable discrepancy between values and behaviour—that people naturally seek to resolve. Many who experience this dissonance may label themselves as “porn addicts” or “sex addicts,” as framing it as an addiction shifts the blame from themselves to a perceived disease.

In some ways, identifying with that label can act as a self-protective factor, explaining the discomfort stemming from their behaviour and values being misaligned.

This is one of those controversial concepts, but it’s not just about moral conflicts. For some people, there are compulsive urges to engage in sexual behaviour, which could include pornography use or partnered sexual activities. These compulsions may be linked to underlying mood disorders or conditions such as obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). So, yes, there can be compulsive reasons for engaging in certain sexual behaviours, but this is distinct from the concept of addiction. The evidence doesn’t align with the idea of addiction.

For example, when considering addiction, one key characteristic is the development of tolerance—needing more and more of the behaviour or substance to achieve the same level of satisfaction. Data does not support the idea that pornography use leads to a buildup of tolerance over time. Many aspects of compulsive behaviour do not match up with the addiction model, and a compulsive disorder explanation often makes more sense in these cases. Thus, I believe it’s more accurate to frame these issues as involving moral conflicts or compulsive behaviour rather than addiction.

Section 8: North American Sex Education Systems

Jacobsen: Regarding current educational models or knowledge frameworks, what are North American systems getting right and wrong about healthy sexuality, sexual desires, sexual behaviours, and sexual psychology, especially in the K-12 education system?

Lehmiller: In the United States, sex education is a patchwork of laws. Not every state even requires sex education for adolescents. Currently, only 29 states mandate sex education for adolescents, leaving a significant number of states where it isn’t required at all. Even among the states where it is mandated, only about 15 require the education provided to be medically accurate. This is astonishing because it means there are over a dozen states where students are taught sex ed that does not need to be factual or useful—it could be anything.

This is where we struggle: there is no consistent framework in place to ensure high-quality sex education is delivered. Most sex education happens at the local level, determined by local school boards and often influenced by parents and community opinions, which can lead to varied and sometimes inadequate sex education. The lack of uniform standards is one of the biggest issues, as it leads to a disparity in the quality and comprehensiveness of sex education across the country.

The way that most sex education works in the U.S. is at the local level, where local school boards determine what should be taught, often with input from parents, PTA boards, and other community stakeholders. Many of the people who are most vocal about sex education are those who are against it being taught in the first place. This is why abstinence-based sex education remains prevalent in the U.S. There are areas where comprehensive sex education is offered. Many of these programs do quite well. However, many students still receive education that needs to be more comprehensive.

When considering effective models for teaching younger adults and adolescents about sex, we need to look at what other countries are doing. I include this in my study abroad courses for sex therapists, researchers, and educators. We visit other countries and speak with local sex educators to understand their approaches and what we can learn from them. My favourite program is in the Netherlands. They have a program called Long Live Love, which is used in most Dutch schools.

It’s a program that begins in kindergarten, adding new components as children progress through their education. I know some people might be taken aback when they hear “sex ed for kindergartners” and wonder what that entails. It doesn’t involve teaching young children about intercourse or explicit content. Instead, it focuses on teaching them the names of their body parts and developing communication skills. For example, children learn how to communicate about things like good and bad touch and how to express their boundaries.

This approach lays the foundation for improved communication skills from an early age. Teaching kids the proper names for their body parts is crucial for safety. If a child experiences sexual assault, being able to report what happened accurately is essential. Providing them the language to communicate with parents or trusted adults can help keep them safer. The Dutch program is age-appropriate and evolves to provide the necessary knowledge at different developmental stages.

As children grow, the curriculum focuses on puberty and bodily changes. Beyond that, it covers what they need to know about sex, staying safe, and forming healthy relationships. One often-missing element in sex education is the relationship component. Sexual activity always occurs within some relational context, so separating discussions of sex and relationships is unhelpful. This ties back to my earlier point that relationship researchers often overlook sex, while many sex researchers don’t focus on relationships. We need to discuss both together to some extent.

I highly recommend the Long Live Love program in the Netherlands. We could learn much from it to improve our programs, which need to be improved in many ways.

Section 9: Consensual Non-Monogamy

Jacobsen: Let’s shift to consensual non-monogamy. These relationships can come with challenges, such as jealousy and societal stigma. How do individuals navigate those relationships, and how is the cultural context of these relationships evolving?

Lehmiller: Consensual non-monogamy involves relationships where people have more than one sexual or romantic partner at the same time, with everyone’s consent. These relationships are on the rise, and interest in them is increasing. For instance, Google searches related to polyamory and open relationships have been on the rise over the last 10 to 20 years.

We also see increased media depictions of people in non-monogamous relationships, leading to greater cultural recognition and awareness compared to the past. While these relationships are often portrayed as more evolved or progressive, some people talk about how jealousy doesn’t exist. Partners enjoy each other’s happiness; that is not the whole story. Many individuals in polyamorous or consensually non-monogamous relationships still face challenges, and jealousy can and does arise in these relationships.

Navigating consensual non-monogamy can be difficult because many people don’t have a clear framework or template for how these relationships should function. Those who open their relationships often don’t know what ground rules and boundaries should be discussed and established up front, which can lead to complications. Some people think that opening up a relationship will solve existing sexual issues. Still, they may find that it introduces a new set of challenges.

Consensual non-monogamous relationships can work, and when comparing monogamous and non-monogamous relationships, satisfaction levels are often similar. Either type of relationship can be fulfilling, but each comes with its own unique set of issues. Entering a consensually non-monogamous relationship means trading in for different challenges that need to be navigated with your partner. Reading guidebooks and resources can be helpful for those considering opening up their relationship. For example, books like Opening Up, More Than Two, and The Ethical Slut are valuable resources for understanding potential issues and learning how to navigate these relationships healthily.

Section 10: Societal Stereotypes and Misconceptions in Sex Research

Jacobsen: As social conversations about sexuality and sexual satisfaction evolve, how are people who are more exploratory still stereotyped? How is sex research itself stereotyped, and what misconceptions persist in the public eye?

Lehmiller: It’s interesting to see how societal attitudes have shifted. Over the past few decades, society has become more sex-positive in many ways. For example, public opinion polls in the U.S. and many Western countries show increasing acceptance of people who are not heterosexual, sex outside of marriage, divorce, and having children outside of marriage. By many measures, we are more accepting than we were in the past.

However, sex negativity still exists. Sexual double standards persist, with women often judged more harshly than men for exploring their sexuality. Slut-shaming, though more recognized now than before, still happens despite efforts to reduce it. This reflects how society continues to stereotype people who are more sexually exploratory.

Sex research, too, is often stereotyped or misunderstood. Historically, it has been controversial. Dr. Alfred Kinsey’s research in the 1940s and 1950s was met with intense backlash, and to this day, sex research remains contentious. This makes it difficult for researchers to secure funding, as the U.S. government is hesitant to fund studies that don’t focus on negative aspects of sex, such as STIs or teen pregnancy. This reluctance extends to research on positive aspects of sex, like pleasure or fantasies, which often face significant challenges in obtaining financial support. The field is challenging due to the lack of broad acceptance and limited funding for crucial research.

Section 11: Public Perception of Sex Research

Jacobsen: How does the general public view sex research?

Lehmiller: Sex research has always been controversial. If you go back to the pioneering work of Dr. Alfred Kinsey in the 1940s and 1950s, it generated explosive controversy. Even today, sex research remains a contentious topic within the public eye, making it difficult for sex researchers to secure funding for their work. In the U.S., obtaining funds for sexuality research is challenging. Researchers often need to rely on private organizations rather than government grants because the U.S. government is hesitant to fund research in the realm of sexuality that does not focus on negative aspects, such as STIs or teen pregnancy prevention.

This extends to areas like sexual pleasure or fantasies, which rarely receive government funding. As a result, the field can be difficult to work in, lacking widespread acceptance, and often facing financial obstacles when conducting meaningful research.

Jacobsen: Thank you very much for your insights today. I appreciate it.

Lehmiller: Thanks so much for having me.

Discussion

The interview between Scott Douglas Jacobsen and Dr. Justin J. Lehmiller offers a nuanced examination of human sexuality, highlighting the intricate interplay between individual behaviors, societal norms, and educational frameworks. Dr. Lehmiller’s insights challenge prevalent misconceptions, such as the underappreciation of the clitoris in human sexuality and the oversimplified notion that “opposites attract.” By grounding these discussions in empirical research, the interview underscores the importance of scientific inquiry in debunking myths and fostering a more accurate understanding of sexual health and behaviors. One of the significant themes explored is the generational shift in sexual behaviors and relationship preferences. Dr. Lehmiller highlights that younger adults today are experiencing delayed adulthood, resulting in fewer sexual partners but a greater inclination towards kinkier sexual practices. This shift may reflect broader cultural and societal changes, including the impact of technology and social media on personal relationships and sexual expression. The discussion on consensual non-monogamy further illuminates how evolving relationship structures require new frameworks and resources to navigate challenges like jealousy and societal stigma effectively.

The critique of North American sex education systems, contrasted with the Netherlands’ “Long Live Love” program, underscores the disparities in how different cultures approach sexual education. Dr. Lehmiller advocates for comprehensive, age-appropriate sex education that evolves with developmental stages, emphasizing the importance of communication skills and accurate knowledge from an early age. This perspective aligns with existing literature that emphasizes the role of education in shaping sexual health and satisfaction. Additionally, the interview delves into the role of social media in shaping perceptions of sexuality. While social media platforms offer opportunities for education and connection, they also pose risks through the spread of misinformation and the promotion of unrealistic standards. Dr. Lehmiller’s discussion of “performative dating” and challenges like “No Nut November” illustrates the complex ways in which social media influences individual self-perception and relationship dynamics.

Furthermore, the exploration of concepts like porn addiction and sex addiction reveals the complexities and controversies within the field of sexual psychology. Dr. Lehmiller challenges the validity of these addiction models, arguing that many reported cases are better understood through the lens of moral conflicts or compulsive behaviors rather than true addiction. This perspective calls for a more nuanced approach to addressing problematic sexual behaviors, one that considers underlying psychological factors and personal values. Overall, the interview emphasizes the necessity for ongoing research and improved educational frameworks to foster a more informed and accepting societal attitude towards human sexuality. Dr. Lehmiller’s expertise highlights the interplay between biological, psychological, and social factors in shaping sexual health and behaviors, advocating for policies and educational programs that reflect the complexity and variability of sexual experiences across different life stages and cultural contexts.

Methods

The interview with Dr. Justin J. Lehmiller was conducted on November 4, 2024, and subsequently published on January 22, 2025. A semi-structured interview format was employed to facilitate an in-depth exploration of Dr. Lehmiller’s expertise in human sexuality. This approach allowed for both guided questions and open-ended responses, enabling a comprehensive discussion of various topics such as sexual fantasies, consensual non-monogamy, sex education, and the impact of social media on sexuality. The interview was recorded with the consent of both parties to ensure accuracy in transcription. Following the interview, the recording was meticulously transcribed verbatim and organized into thematic sections based on the subjects covered. This organization ensured clarity and coherence, allowing readers to navigate the complex topics discussed seamlessly. The structured methodology of this interview aimed to provide a holistic understanding of human sexuality by addressing both biological and psychosocial factors. By focusing on Dr. Lehmiller’s extensive research and practical experiences, the interview seeks to bridge the gap between academic theories and real-world applications in the field of sexual psychology.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current article. All interview content remains the intellectual property of the interviewer and interviewee.

References

(No external academic sources were cited for this interview.)

Journal & Article Details

- Publisher: In-Sight Publishing

- Publisher Founding: March 1, 2014

- Web Domain: http://www.in-sightpublishing.com

- Location: Fort Langley, Township of Langley, British Columbia, Canada

- Journal: In-Sight: Interviews

- Journal Founding: August 2, 2012

- Frequency: Four Times Per Year

- Review Status: Non-Peer-Reviewed

- Access: Electronic/Digital & Open Access

- Fees: None (Free)

- Volume Numbering: 13

- Issue Numbering: 2

- Section: A

- Theme Type: Idea

- Theme Premise: “Outliers and Outsiders”

- Theme Part: 33

- Formal Sub-Theme: None

- Individual Publication Date: January 22, 2025

- Issue Publication Date: April 1, 2025

- Author(s): Scott Douglas Jacobsen

- Word Count: 3,861

- Image Credits: Photo by Sushil Nash on Unsplash

- ISSN (International Standard Serial Number): 2369-6885

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Prof. Lehmiller for his time and willingness to participate in this interview.

Author Contributions

S.D.J. conceived and conducted the interview, transcribed and edited the conversation, and prepared the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

License & Copyright

In-Sight Publishing by Scott Douglas Jacobsen is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

© Scott Douglas Jacobsen and In-Sight Publishing 2012–Present.

Unauthorized use or duplication of material without express permission from Scott Douglas Jacobsen is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links must use full credit to Scott Douglas Jacobsen and In-Sight Publishing with direction to the original content.

Supplementary Information

Below are various citation formats for Conversation with Professor Justin Lehmiller on Sexology and Human Sexuality.

Jacobsen S. Conversation with Professor Justin Lehmiller on Sexology and Human Sexuality. January 2025;13(2). http://www.in-sightpublishing.com/lehmiller

Jacobsen, S. (2025, January 22). Conversation with Professor Justin Lehmiller on Sexology and Human Sexuality. In-Sight Publishing. 13(2).

JACOBSEN, S. Conversation with Professor Justin Lehmiller on Sexology and Human Sexuality. In-Sight: Interviews, Fort Langley, v. 13, n. 2, 2025.

Jacobsen, Scott. 2025. “Conversation with Professor Justin Lehmiller on Sexology and Human Sexuality.” In-Sight: Interviews 13 (2). http://www.in-sightpublishing.com/lehmiller.

Jacobsen, S. “Conversation with Professor Justin Lehmiller on Sexology and Human Sexuality.” In-Sight: Interviews 13, no. 2 (January 2025). http://www.in-sightpublishing.com/lehmiller.

Jacobsen, S. (2025) ‘Conversation with Professor Justin Lehmiller on Sexology and Human Sexuality’, In-Sight: Interviews, 13(2). http://www.in-sightpublishing.com/lehmiller.

Jacobsen, S 2025, ‘Conversation with Professor Justin Lehmiller on Sexology and Human Sexuality’, In-Sight: Interviews, vol. 13, no. 2, http://www.in-sightpublishing.com/lehmiller.

Jacobsen, Scott. “Conversation with Professor Justin Lehmiller on Sexology and Human Sexuality.” In-Sight: Interviews, vol. 13, no. 2, 2025, http://www.in-sightpublishing.com/lehmiller.

Jacobsen S. Conversation with Professor Justin Lehmiller on Sexology and Human Sexuality [Internet]. 2025 Jan;13(2). Available from: http://www.in-sightpublishing.com/lehmiller

Note on Formatting

This layout follows an adapted Nature research-article structure, tailored for an interview format. Instead of Methods, Results, and Discussion, we present Interview transcripts and a concluding Discussion. This design helps maintain scholarly rigor while accommodating narrative content.

#ConsensualNonMonogamy #HumanSexuality #LongLiveLoveProgram #PornAddiction #SexAddiction #sexEducation #SexualFantasies #SexualHealth #SexualPsychology #SocialMediaImpact

Halle Berry isn't holding back on her ex-husband's "sex addiction" claims. Is it a convenient excuse or a real struggle? Weigh in on this fiery debate. #HalleBerry #EricBenet #SexAddiction #CelebrityDrama #FierceLove #FierceMillennial

We've had some incredible guest blogs lately, so let's do a little round-up of the amazing posts from the last few weeks.

First: @bigedmagusson gave a powerful and thoughtful account of his journey through SAA and an important realisation about #SexAddiction vs #libido:

https://www.girlonthenet.com/blog/sex-addiction-my-libido/ #NSFW

"The less I used sex to numb myself, the better the sex got."

NEW guest blog by Big Ed Magusson, about 'sex addiction' and libido...

https://www.girlonthenet.com/blog/sex-addiction-my-libido/ #SexAddiction #libido #NSFW