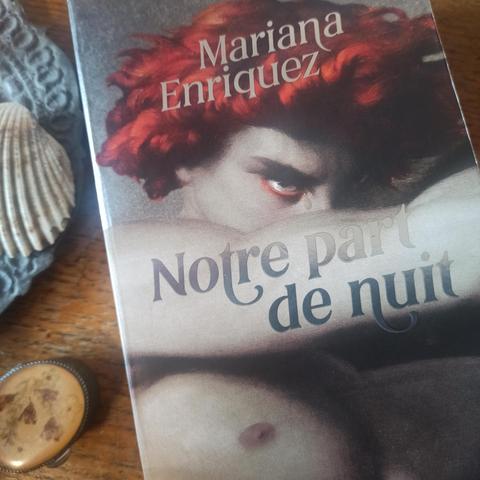

#literature #MarianaEnriquez #OurShareOfNight #horrorliterature #gothicbooks

#literature #MarianaEnriquez #OurShareOfNight #horrorliterature #gothicbooks

My book Witch's Familiar & Whimsical Stories is appropriate reading all year round, but especially this time of year.

#WritingCommunity #Witches #dragons #blackcats #gothic #gothicliterature #gothicbooks #writing #Halloween #SpookySeason #Samhain

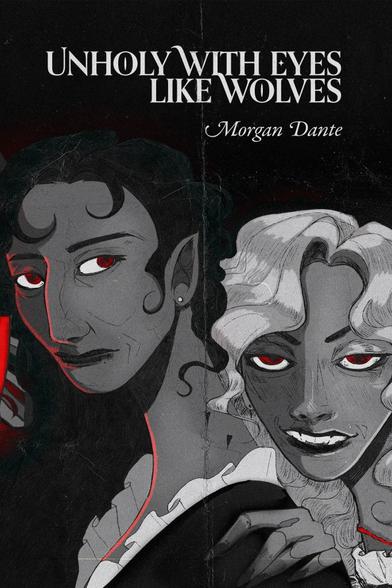

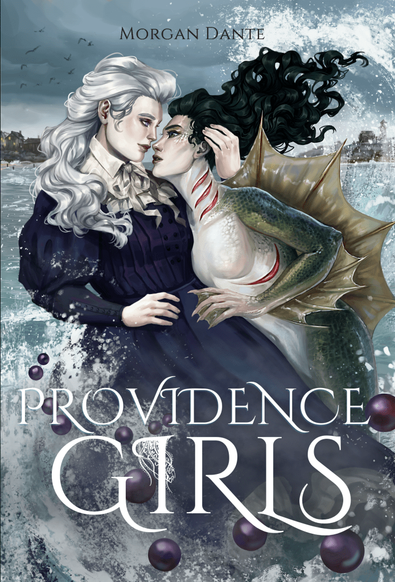

Author Spotlight: Morgan Dante

Morgan Dante (they/them) is an author of romance, fantasy, and horror. They especially enjoy Gothic literature and vampires.

Their best known works are the cosmic horror romance Providence Girls and the Judas Iscariot/The Devil romance The Saint of Heartbreak.

Author Links

Author website: morgandante.com

TikTok: @morgandante

Instagram: @mdantesinferno

Bluesky: morgandante.bsky.social

Twitter: @morgansinferno

Tumblr: ghostpoetics

We’re here to spotlight your work, which falls under the dark Gothic queer romance umbrella. What is your relationship with Gothic Romance, and how did you come to write it?

I love Gothic romance, whether it’s contemporary Gothic romance or the more nineteenth-century use of the word, such as Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights. When it comes to writing it, for the longest time, I have always preferred reading, watching, and writing horror. It is the number one genre to me.

I have always been interested in the macabre, especially when it intermingles with sexuality and desire. I find the themes of grief, trauma, repression, and obsession all intriguing to explore in the context of the Gothic. I studied a lot of Gothic literature when I was getting my BA in English, and I enjoy everything I mentioned as well as the complicated depiction of dark subjects and the grotesque.

What queer rep can readers expect to find in your work, and how do queerness and Gothic romance fit together in it?

This is an excellent question, albeit a complicated one. Most of my characters, though not all, are bisexual. I am bisexual, and I tend to just default to that. As someone who, for a long time, has identified from genderqueer to trans masc, I tend to write characters who, even if they are technically cis, are gender non-conforming.

They have discomfort with their gender, and I tend to believe even cishet people can experience these feelings and should be given space to explore these experiences, too; but sometimes with a fictional character, depending on what part of their character journey you’re writing about, they may not be entirely cognizant of how to process their feelings.

This is especially true in historical pieces in societies where concepts like homosexuality were more tied to physical actions rather than seen as complex identities and communities until a certain point in time. And of course, while trans people have existed for a long time, there is no singular idea of what being trans means. Many cultures do not use the same framing for identities and communities that people in the U.S. do, as America is a melting pot but only one part of the world.

Azzie from Providence Girls deals with complicated feelings about her gender; overall, she does have body dysmorphia, but there is also some dysphoria, too. As per “The Thing on the Doorstep,” she is wary of her more masculine traits because her father switched her soul with his and lived in her body. Her more masculine traits are not bad or a sign of wrongness, though she wonders if these aspects of her are a “residue” of the magical spell he inflicted on her, but she was wearing pants and smoking cigars as a kid before he did that. She struggles with feeling disconnected from her body.

Just when she tries to become comfortable in her body, she begins transforming. She’s half-Deep One, and in The Shadow Over Innsmouth, it is established that human men were forced to have Deep One wives; the Deep Ones from the sea are said to be female, but I am not necessarily sure whether these fish-people from an ancient underwater city would necessarily have the same binary.

I am interested in how we perform gender as impressed upon us by society.

Léon in A Flame in the Night and Witch Soul is genderqueer; he was a soldier, but living in 1920s Paris, he is generally rather feminine and okay with that. He is okay with being called a man, but he does also occasionally refer to himself with she/her, although it might not be immediately evident because he does it when he refers to himself in French. He likes to knit and also likes to wear dresses.

Same with Lucifer in The Saint of Heartbreak. While I do occasionally label The Saint of Heartbreak as “technically” M/M, Lucifer is not a man, even if he uses he/him; I view fallen angels as not being born with gender and viewing a lot of labels and roles as arbitrary. He does not mind what people call him, and when I wrote about him and Lilith, I mention that both of them were pregnant with children, and there are times he has different genitalia and other times where I don’t explicitly mention what genitalia he has because I find it superfluous to getting the point across, and it has no bearing on what gender he considers himself. It just isn’t something he thinks about, and being reminded of it by a mortal tends to momentarily bemuse or frustrate him.

As for Gothic romance, I find that a lot of Gothic literature, in exploring themes like emotional reactions to trauma and desire, have often conflicting but intriguing depictions of gender. We have Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, which we can view as very much a “lesbian preys on an innocent girl” negative stereotype, but also, there are few things as darkly romantic as lines like “to die as lovers may, to die together so that they may live together.”

Bram Stoker’s Dracula has plenty of conflicting discourse about its depiction of women. Jonathan Harker essentially takes on the role of the Gothic heroine who is trapped in a castle with the monster, who cooks and cleans for him. Dracula tells his brides that Jonathan belongs to him and carries him to bed after Jonathan passes out. Jonathan, horribly traumatized from the abuse and his escape, begins to fixate on his kukri knife, a phallic object; after being a relatively mild-mannered man traumatized by Dracula, he seems to lean into violence as a way to reclaim himself. However, his most grounding trait is his love and devotion for Mina.

The text creates a clear dichotomy between the good woman (Mina) and the bad woman who becomes more seductive as a vampire (the brides, Lucy). Mina, a woman who works, lives while her upperclass sensitive and innocent friend dies twice. Mina herself is critical of the New Woman, a woman who challenges social roles, while she herself challenges them.

Van Helsing says that Mina is a good woman because she has the heart of a woman and the brain of a man, which reinforces the sexist idea of women=emotion and men=logical. However, without Mina copying their notes and using her psychic connection to Dracula after his nightly assault, they would not have defeated Dracula.

Her mix of competence and compassion are engaging. It’s actually the men’s efforts to exclude her, even if out of a chauvinistic idea of protecting her because they care for her, that lead to negative consequences; even while she’s afflicted, they defeat Dracula with Mina.

The lines that are seemingly stark aren’t; it’s a novel of contradictions written by an Anglo-Irish Protestant man who was fascinated by scientific progress but not especially revolutionary. A man who was close friends with Oscar Wilde (Bram Stoker’s wife, actress Florence Balcombe, was with Oscar Wilde until she married Stoker and broke Wilde’s heart), visiting Oscar Wilde after his imprisonment, but then becoming vehemently homophobic in old age.

It is important to view the book in its own time; yes, there are many things by contemporary stands that are regressive, and even aspects from the 1890s, but there is also transgression and places to find queer subtext.

To me, Gothic romance and Gothic horror are great places to explore liminal and uncertain spaces, and queerness is all about questioning and expanding these ideas.

What is the interplay between monstrosity and attraction in your work, and why do you find yourself returning to these themes?

I consider Providence Girls to be a monster romance, and vampires are my favorite monsters.

Ocean Vuong once said, “To be a monster is to be a hybrid signal, a lighthouse: both shelter and warning at once.” I am interested in monstrosity as a way to show acceptance, a very “come as you are” idea.

Vin cares about Azzie turning into a monster because it’s a very painful transformation, but she isn’t deterred or unattracted to her because of that; she would be perfectly happy having a Deep One as her eternal companion, and indeed she is when they reunite. I am also compelled by the dual nature of monsters as both “shelter and warning.”

Yes, a vampire is dangerous. They are monsters who need blood to live, but also, they have the power to keep those they love safe–or to keep themselves safe.

For Noémie in Unholy With Eyes Like Wolves, vampirism means freedom, but it has a price; it isn’t a wholly good thing. Erzsébet at the ending is still grieving after all she has endured.

Vampirism in particular for me is interesting because I do consider it as a possible vehicle for transgression and freedom because one has the strength and powers to do things that were previously off-limits, but if the vampirism wasn’t asked for, there is an element of violation that leads to some messy and complicated feelings that could be intriguing to explore if done right; I am always bothered at analysis of Dracula that sees Dracula’s assaults on Lucy and Mina as him bestowing them with positive transgressiveness, a gift he has given the women, as the ways they are interesting women exist before he forces them to feed from his breast–which, very interesting portrayal!

I am obsessed with the maternal imagery Stoker decided to employ by having Mina feed by drinking from Dracula’s chest. But I don’t like him getting the credit for making the women interesting and transgressive…by traumatizing them. All that said, I return to monsters to explore themes of love and loneliness from the perspective of outsiders.

In PROVIDENCE GIRLS: A sapphic horror romance set in Great Depression New England, one of the women is changing into a Deep One (Lovecraftian mythos, from HP Lovecraft’s story THE SHADOW OVER INNSMOUTH. What was the inspiration behind this story, and what did you most enjoy about writing and developing it?

Providence Girls has three primary inspirations, all written by H.P. Lovecraft: “The Thing on the Doorstep” (Asenath Waite); “The Dunwich Horror” (Lavinia Whateley); and The Shadow Over Innsmouth.

Azzie and Vin are of course from the first two stories, and “The Thing on the Doorstep” mentions that Asenath is from Innsmouth and has oddly large eyes that hint at her being a Deep One hybrid.

If the events of the short story were different, she likely would have begun transforming sometime, which was part of the inspiration.

Back in 2018, I became ill from a stomach ulcer and spent a good amount of time wiped out. During this time, I read a used collection of H.P. Lovecraft stories cover to cover. Reading these stories chronologically was great because you see the change in writing and the way many of the stories connect and old characters return.

Lovecraft was a flawed and deeply bigoted man.

It is fascinating, however, how creators from Victor LaValle to Ruthanna Emrys to Guillermo del Toro engage with his stories, many of them giving voices to characters (and real life people) he maligned.

LaValle gives a perspective to one of the Black men in Red Hook who are vilified “The Horror at Red Hook.”

Emrys explores the perspective of a Deep One character interned by the government and then released.

Del Toro explores how disabled and queer characters empathize with the fish monster.

These artists humanize the Lovecraftian “villains” and show another side, monsters as mirrors and figures of empathy. Lovecraft, also a writer of contradiction, reviled outsiders and depicted many of them horribly, but he also excelled at writing outsiders.

He even wrote a short story called “The Outsider” where the lonely main character proclaims, “I know always that I am an outsider; a stranger in this century and among those who are still men.”

Though there is no excuse for him racism, and he became slightly more open to others (but never fully conceding all his repugnant views) as he aged, Lovecraft died poor and struggled with emotional abuse from his mother and suicidal ideation. He was a deeply reactionary and afraid man. It is interesting to see the change in his narratives once we get to The Shadow Over Innsmouth.

In earlier works like “Dagon,” the work typically follows the premise of the narrator recounting a horror he experienced in the past and, succumbing to madness, possibly planning his suicide.

Characters who are traumatized or different experience monstrosity and want to die.

When we get to The Shadow Over Innsmouth, the narrator discovers after his ordeal escaping the hamlet that he is also a Deep One hybrid. This makes him suicidal, but then he accepts who he is and plans to help the other Deep Ones, apprehended by the government, escape the camps they’ve been placed in.

The Shadow Over Innsmouth is complicated because there are not especially subtle allusions to Lovecraft’s anxieties about miscegenation, but there are also aspects that made me read it as a coming out story near the end–that process of devastation and grief over being something you are told you should hate, a self-loathing that sometimes leads to thoughts of self-harm, and then finding self-acceptance.

Of course, my interpretation of the story is that the narrator is being depicted as “turning bad” and still succumbing to madness by accepting who he is. The Deep Ones are not depicted as sympathetic, after all. Mind, Lovecraft is portraying them as dangerous monsters who are rightfully placed into camps. But there are interpretations that see this less despairing ending as strangely hopeful; it’s a change in Lovecraft’s usual story progression to have the protagonist not die in this moment of embracing the horror, but to instead have some sort of ecstasy.

I was interested in the exploration of the narrator’s conflicted feelings about his inevitable change. After reading “The Thing on the Doorstep” and “The Dunwich Horror,” I was struck by the parallels between the women in these stories who would then become Azzie and Vin.

They are both women used by their occultist fathers and ultimately doomed. Lovecraft didn’t have many female characters. He was no feminist, no shock there, but while he thought that women’s minds didn’t cover the same ground as men (because of what he considered to be social conditioning rather than biology), he thought that if women had less of a capacity to be logical, the difference was negligible enough not to matter and was accepting of growing women’s independence.

His short-lived marriage, after all, was with an older woman who traveled to work, though that relationship with Sonia Greene had issues such as his outspoken antisemitism and xenophobia…while married to a Ukrainian (or what is now Ukraine) Jewish woman.

Still, however, Lovecraft viewed men and women as different in a way that made him uncomfortable writing about women. His female characters are sparse and, as we see, the most notable ones follow similar archetypes. I just thought it would be interesting if Asenath Waite and Lavinia Whateley ever met and were in a room together. What would they talk about? How would they react to their traumas? Admittedly, when the idea came, I didn’t immediately have a grasp on balancing internal and external conflicts, but I very soon realized the external conflict and ticking clock aspect to the relationship would be Azzie’s progressing transformation.

I also wanted to capture different ways of handling grief and trauma. Vin cannot let go of the past, even when she tries. She cannot let go of her sons. Azzie, on the other hand, represses and tries to think about only the present. Both of these responses are understandable and come with their own complications.

The entire story is a play between the past and present.

Despite Providence Girls being, in retrospect, one of the books I struggled to write the most, there is a lot that I enjoyed about writing it. I liked playing with the very different voices, the dreamy and languid voice of Vin compared to Azzie’s more stoic and straightforward nature. I loved looking at old photographs of East Providence and bringing the world to life. I liked playing with the generally dark and bleak cosmic horror of Outer Gods who either don’t care about humanity (Yog-Sothoth) or are outwardly hostile (Nyarlathotep), and then turning it on its head. Overall, it’s one of my proudest works.

Two of your books play with more human “monsters” or “villains” – Judas Iscariot, and Elizabeth Bathory. What research did you do for these figures, and how did you take the existing legends around them to craft them into these stories – UNHOLY WITH EYES LIKE WOLVES and THE SAINT OF HEARTBREAK?

For research about Elizabeth Bathory, my main sources come from her private letters published by Kim L. Craft and Tony Thorne’s Countess Dracula: The Life and Times of Elisabeth Bathory, the Blood Countess.

I was always dissatisfied trying to write about her because much about Bathory focuses on the lurid, graphic depictions of murders and not her place in the world she lived in; I could never really get a sense of late sixteenth-century and early seventeenth-century Hungary. It wasn’t until I read Craft’s collection of letters and Thorne’s book, although the latter I was admittedly skeptical of because of the title, that I got what I wanted: books that explored Hungarian culture and politics at the time, as well as showing what it was like to be in control of so much land as a woman whose husband was often away.

I could actually envision her world. I was always fascinated by her, even the most dramatic and wild portrayals, such as in Cradle of Filth’s album Cruelty and the Beast.

That said, I feel like a lot of portrayals of Bathory are steeped in misogyny; she is often portrayed in a way that reminds me of the “incontinent” (sexually uncontrolled, in this context) she-wolf Dante mentions at the start of Inferno: a bloodthirsty and lascivious woman who is evil most of all in her inability to control her urges.

I also feel like when mostly American and British people engage with historical figures like Bathory or Vlad the Impaler, they are focused on the most grotesque details and inevitably engage in xenophobia against Eastern Europeans.

While there was brutality because nearly all of Europe in the medieval period and early modern era had cruelty the lords inflicted on peasants or horrible war crimes, I’m always bothered by the idea of these periods being uniquely full of ignorance and bloodshed. I’m especially bothered by the depiction of Eastern Europeans as uniquely “barbaric,” bloodthirsty, and sexually deviant compared to their Western European counterparts.

This is usually tied into antisemitic tropes and a stew of negative depictions of Romanians, Hungarians, the Romani, and the Ottomans.

Besides the portrayal of the Romani as agents of the evil Count, Bram Stoker uses physiognomy–the study of facial features to determine character, which employs racist pseudo-science–to tell us that Count Dracula in his Transylvanian castle is decadent and morally corrupt.

I want to be clear: Bathory ruled over land in a time where there was a brutal suppression of peasant revolts. None of this is to say that the aforementioned historical figures did not commit violence ever. I don’t think Bathory was a perfect woman who never did anything wrong in her life. She was very likely harsh and, given that she performed the role of the feudal lord with her husband at war for much of her life, she was probably ruthless. If she were to punish someone who angered her, there is nothing to say that she didn’t engage in torture; sadly, this was no outlier. She raised taxes on the serfs without worry of recourse; that was all simply the dynamic between a feudal landowner and serfs. I don’t think she was just a kind woman, even if she did do good things as part of her duties.

However, do I believe that she murdered hundreds of women and girls and was a blood-bathing Satanist? No.

From what I have read, I am convinced that certain people imprisoned or executed for accusations of Satanic murder were victims of political plotting, an escalated personal grievance that took advantage of the devil worship/heresy hysteria, or an effort to seize land.

For Bathory, I think the Habsburg Crown was retaliating against a prominent Protestant (Calvinist) woman who insisted that they pay their debts to her.

Why the blood-bathing Satanist lesbian murderer accusation? Well, such accusations are quite literally life-ending.

Immediately after those rumors spread, and she was immured in her bedroom, she lost all her long allies because that is such a confluence of horrible things that no one wanted to defend her. Who wants to go against the Holy Roman Emperor and defend a woman accused of such horrors? After all, during Bathory’s lifetime, there had already been much tension between the Habsburg Crown, Transylvania, and the Hungarian nobles.

Incensed by the Habsburgs, István Bocskay, a Hungarian nobleman who was previously a liberator of Wallachia until the Ottomans took over again, led an attempted insurrection in Hungary and Transylvania against the Habsburgs. Once peace talks happened, his rebellion went well for him and the Hungarian nobles who sided with him, but he mysteriously fell ill and died. There was great tension between people who wanted an independent Hungary and those loyal to the Habsburgs, who were the Holy Roman Emperors.

There, too, was the tension of being a Calvinist woman, since Calvinism itself was new and controversial at this time, ruled by Catholics.

Bathory herself was careful to never state whether she supported the rebellion or an independent Hungary, even though her older brother supported it. It was a very tumultuous time of alliances and betrayals, and you could lose everything with one wrong action. Bathory tried to be careful in balancing her loyalties while remaining assertive, but in the end, she lost everything and likely died by starving herself to death.

With Unholy With Eyes Like Wolves, I wanted to depict her as not necessarily always a good woman, not always fair or kind, but complicated and navigating a tumultuous time.

Despite including bloody aspects, I tried to integrate more of the history and courtly matters.

With Judas Iscariot, I have been fascinated with him for about ten years. There are so many different ways you can interpret his character.

I am not a fan of “evil Judas” because it doesn’t gel much with the fact that he felt regret and tried to return the silver he received. Besides that, I find depictions that emphasize Jesus Christ’s death as being less the Romans’ doing and more on the “traitorous Jews who are responsible for Christ’s death” to be grossly antisemitic.

Judas in a lot of art is depicted in ways that exaggerate his “Jewishness” with a dramatically hooked nose and red hair whereas Jesus, also a Jew, is depicted as a very bland white guy.

Judas is someone often maligned and used as shorthand for a traitor, but as Oscar Wilde put it, “each man kills the thing he loves.”

Judas is singularly seen as irredeemable, except for another figure: the Devil, who is often seen as beyond God’s all-encompassing forgiveness.

I like exploring the tragedy of Judas’ character, someone who made understandable mistakes and was fearful of how others would be hurt during the rebellion against the Roman Empire.

The rebellion against the enslaving, imperial Romans was of course just, but it isn’t a stretch for Judas to be scared of what Jesus’ actions would mean for the Jewish population subjugated by Rome.

Multiple times, including after Jesus’ death, Rome brutally quelled Jewish riots and enslaved and killed many people. And Judas, portrayed here as a former slave, knows the horrors of Roman power well. He was mistaken to trust Pontius Pilate, but Judas only hoped that Jesus would reconsider what was drawing the most Roman scrutiny; he was horrified and devastated to learn what his actions really meant.

I’m also compelled by narrative parallels. Dante places Satan, Judas, Brutus, and Cassius in the worst part of Hell, the final section of the ninth circle, because they are regarded as the worst traitors.

The Devil betrayed God, and Judas betrayed Jesus, and they are therefore the most loathed and lonely souls in Hell.

In The Saint of Heartbreak, after all the grief and pain, the Devil has closed himself off from feeling love, while Judas is deep down a very compassionate and sensitive man, but they don’t understand one another.

Judas’ depiction is very much an exploration of grief and the circular nature of depression and self-loathing; taken from Dante, Hell is designed as a circle that perpetuates collective pain.

I don’t take a good and evil approach to biblical figures; neither Heaven nor Hell are wholly bad or good. I try to view all characters through the lens of their lived experiences and how that informs their flaws and ways of seeing the world. That doesn’t necessarily mean that they can’t be bad, but I seek to make all characters compelling and human in some way.

Both UNHOLY WITH EYES LIKE WOLVES and SACRAMENT are vampire stories – one sapphic, one achillean. Can you tell us more about the vampire lore incorporated into your stories, and how this blends with the romantic and erotic elements?

I don’t have a strict Morgan Dante vampire lore, so these two books are in some ways very different, but they are both very Gothic, bisexual polycules.

With vampires, I love exploring autonomy, hunger, and desire. Both Unholy With Eyes Like Wolves and Sacrament explore the idea of freedom, although in very different ways; vampirism is more liberating in Unholy Eyes than it is in Sacrament, which has a messier kind of power system involved that makes immortality at times more of a prison.

Both stories, in terms of eroticism, explore themes of power, transgression, and tenderness.

Noémie learns what she wants and what she can do outside of her assigned social role, and Sebestyen begins to change once the main character, Maël, is gentle with him when Maël has every reason to resent him and, in Sebestyen’s mind, continue the cycle of abuse.

With vampirism, it is hard not to acknowledge how power and violence coincide with sex and how characters contend with that and try to find tenderness regardless.

Sex is very important in both of these books in terms of character development and vulnerability. In one way or another, characters who are repressed socially or emotionally (or both) learn about themselves through intimacy.

What can readers look forward to from you in the future?

I have been cycling through different projects, all Gothic and having to do with demons or vampires.

My most pressing project at the moment is an MMF romance that I can best describe as Gaston x Belle x Beast for Beauty and the Beast fans who enjoy a complicated polycule and just really want the Beast to stay a beast.

As a lifelong fan of the animated film, I’m very excited to share this story, although the time period and many elements are darker and very different.

I am also running a Kickstarter for a special edition hardcover of Unholy With Eyes Like Wolves.

Overall, I have many projects I’m excited to share!

Like This? Try These:

- Author Spotlight: Arden Powell Date April 11, 2025

- Author Spotlight: Ezra Arndt Date September 10, 2025

- Author Spotlight: Vesper Doom Date August 28, 2024

#AuthorInterview #AuthorSpotlight #gothicBooks #gothicRomance #queerAdultSFF #queerAuthor #queerBooks #queerFantasy

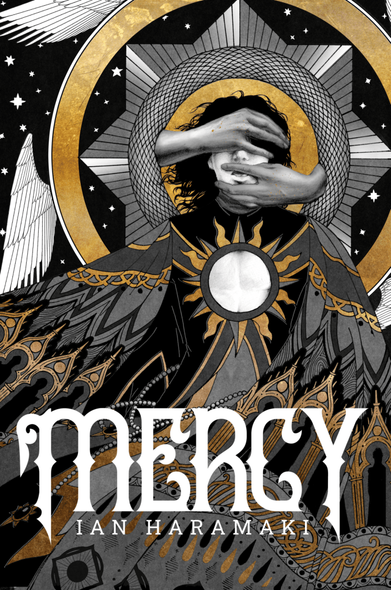

Author Spotlight: Ian Haramaki

Ian Haramaki (he/him) is an author of queer fiction and illustrator of twinks and creatures.

When not writing, he is peddling his wares at fan conventions across the country.

His debut novel is titled MERCY, and he has been included in Devout: An Anthology of Angels edited by Quinton Li, as well as A Queer and Cozy Winter by Rainbow Crate.

Author Links:

Website: cometkins.com

Mercy: books2read.com/MercyNovel

Bluesky: @cometkins.bsky.social

Instagram: @cometkins

TikTok: @cometkinsart

Tumblr: @cometkins

What drew you to writing queer, dark, romantasy for your debut, and can you share some of your writing influences?

I was drawn to this genre in specific because of the origin on these characters. They were originally player characters in a Magic the Gathering based Dungeons and Dragons game.

Ilya was part of the Orzhov guild, while Danya began life as an ex-Boros-turned-Izzet tinkerer. They were very different in that game, but the dark, gothic vibes of the Orzhov guild became the biggest influence for the book.

I’ve always enjoyed the dark and gothic anyway, but that was the main draw of inspiration. My biggest writing influences, on the other hand, are my friends. They’re all so incredible and skilled, and I keep pushing myself to match their caliber of work. I’ve found enjoying their stories and examining how they string words together has done wonders for me.

What are the main themes in Mercy and did these evolve organically through the writing process, or were they deliberate choices?

I think the biggest takeaway from Mercy that I hope other people have, is that there’s always hope for a better future. Sometimes it takes the right person or circumstances to force you forward, but there will be something good on the other side.

I never set out with particular themes in mind when I wrote Mercy, truly the only thought was spite initially, but as the world and characters evolved, I think this became evident. I try to not be too blatant with these things, since it can sometimes feel annoying when the message is too hand-hold-y personally, but I hope that much is clear.

What queer rep can be found in your work, and how do you approach the combination of queerness, Gothic lit, and religious themes?

Mercy specifically contains Gay and Bisexual rep, and my short story for Rainbow Crate, Sir Gawain and His Green Knights, contains a trans masculine character.

I think queerness and the gothic have always gone hand in hand, being that it often deals with the taboo.

While I don’t find queerness itself taboo (as I hope is evident), exploring the feelings that come with being considered taboo, something to be shoved down and aside, is important to me.

A conversation with Oyuna in the book is almost word for word one I had with my own grandmother when it came to her grappling with my transness.

The religious aspect of Mercy has also been fun to explore, speaking as somebody who is actually an atheist.

My own conclusions that I’ve come to over the years are that religion can be a powerful tool for good and evil both. I try to condemn only those that abuse their faith, not those that hold it at all. I also find that there’s divinity in queerness, in self discovery. Love is the most divine thing in the world, and being able to love when the world at large doesn’t want you to is the greatest expression of it.

What did you draw upon in terms of influences, research etc., for the worldbuilding and the angel’s character?

The aforementioned Magic the Gathering is still my greatest influence pull for sure; the biggest thing to know is that the city of Ravnica, where that original DnD campaign took place, is based primarily on eastern Europe.

I took my research to these locations and scoured articles for what I thought would best fit the story.

On top of that, I took acquired knowledge from documentaries and my own antiquing for the late 20s setting.

Danya can be quite anachronistic (on purpose, because I think it’s funny the divine being is so odd and modern), but I swear, everything else is period accurate! They had phones and showers and electric stoves in the 20s! Post industrial revolution tech moved shockingly quick, and I didn’t watch old men repairing radios on youtube for nothing, lol.

What romance tropes can readers expect to find in this book, and what are your favourite tropes to write/read?

The main tropes are probably hurt/comfort (love me some whump), forced proximity, “touch him and die”, and what I like to cheekily call “slow burn for impatient people”.

It’s not actually slow burn, but the way people yell at me about Ilya and Danya’s immediate chemistry, you’d think I’d been edging everybody for 300 pages before they kissed!

I’m personally fond of anything that involves protector/protected as well, and things like friends to lovers. I enjoy when people have a bond together before they get involved.

What are your favourite reader responses to the novel?

Any time somebody tells me they’ve cried because of the book, honestly. It’s always a shock!

One of the first influencers I sent the book to told me she cried twice! I’m a bit emotionally stunted, and it takes a lot to get strong emotion out of me like that, so it’s fascinating to hear.

It’s also really moving to have something you’ve written stir such a powerful response in somebody.

My writing may not be for everybody, but for those it appeals to, it REALLY appeals. It’s completely irreplaceable, and I hope every writer can find at least one reader who responds to their work so strongly.

Like This? Try These:

- Author Spotlight: S.R. Severn Date November 27, 2024

- Author Spotlight: M.T. Envy Date August 27, 2025

- Author Spotlight: Arden Powell Date April 11, 2025

#AuthorInterview #AuthorSpotlight #gothic #gothicBooks #queerAuthor #romantasy #romantasyBooks #transBooks

Meet Amanda Leanne and the Gothic supernatural world of Darkling Cloud. @TheAmandaLeanne #HorrorBooks #GothicBooks #AuthorInterview #AuthorSpotlight

https://cmrosens.com/2025/05/30/author-spotlight-amanda-leanne/

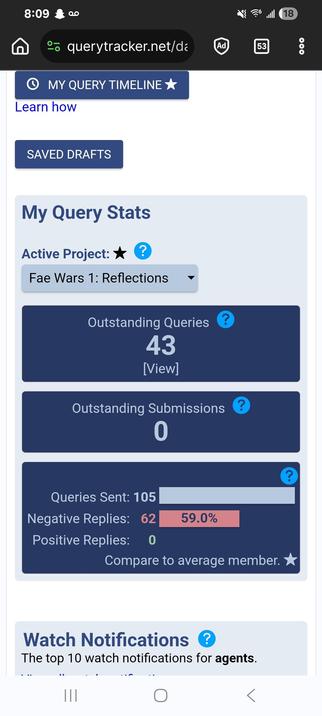

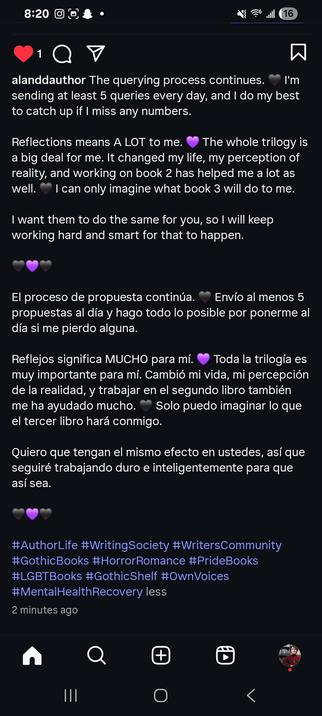

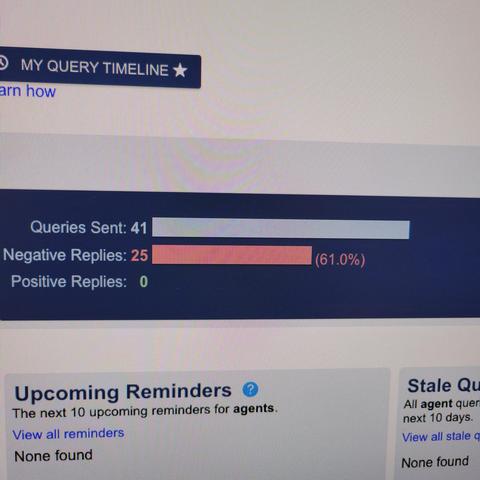

It's not forbidden to get discouraged. What I do forbid myself is to give up. Someone has to say yes at some point.

...

No está prohibido desmotivarse. Lo que sí me prohíbo es rendirme. Alguien tiene que decir que sí en algún momento.

...

#AuthorsLife #WritersLife #WritingSociety #WritersCommunity #GothicBooks #IndieAuthor #AuthorsSociety #BookishCommunity #Bookshelves #FantasyBooks

Meet @emrowene (he/they) and their web serial "Fractured Magic", a gothic epic fantasy in 3 volumes! Catch up with the story so far. #Fantasy #Gothic #FantasyBooks #GothicBooks #WebSerial

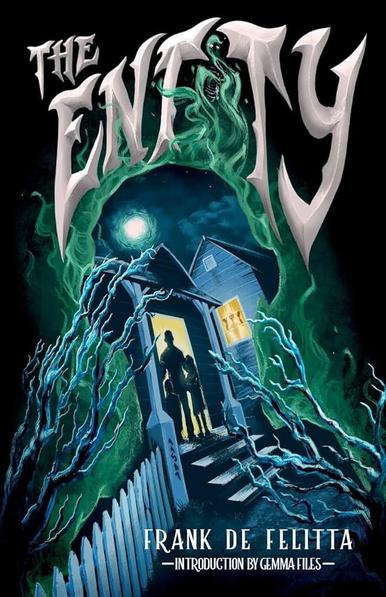

BOOKS FOR HALLOWEEN

The Entity by Frank De Felitta

#Books #horrorbooks #gothicbooks #halloween2024 #halloween2024countdown #paranormalbooks #supernaturalbooks #ghosts #ghoststories #ghosthunting