Whispers on Stone: Why Paleolithic Rock Art Still Speaks to Us Today

(And why I’m moving halfway across the world to listen)

In the Glow of Firelight

Night in the Paleolithic. Firelight flickers along the limestone walls of a shelter, casting movement across the contours of a horse etched in stone, its musculature defined by the shifting interplay of shadow and flame. Beside it, an aurochs emerges, its horn arcing like a crescent moon across the rock face. These are not merely pictures — they are echoes. Echoes of the earliest human voices, carved into stone, suspended in time yet pulsing with presence.

Soon, I’ll be in Portugal’s Côa Valley, where these voices still speak. I’m not going to analyze them from behind glass — I’m going to listen. To stand among the engravings not as a distant observer, but as a human being among ancestors.

Photo by Stijn Nuttin on Pexels.com1. The Meaning Behind the Marks

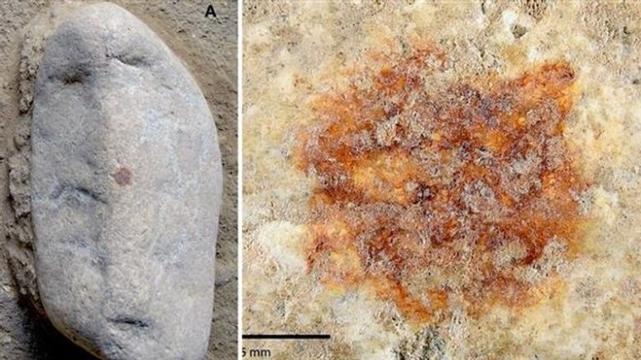

Paleolithic rock art represents one of the earliest and most profound expressions of symbolic thought — a leap in human cognition. With engraved ochre from South Africa’s Blombos Cave dating back over 70,000 years (Henshilwood et al., 2002), we know that abstract expression emerged long before the rise of cities, agriculture, or writing.

These are not decorative flourishes. They are tools of memory, myth, and meaning. They express a need to communicate not only information but emotion, connection, and transformation. The subjects — animals, births, shamanic figures — appear across continents, hinting at a shared symbolic heritage stretching deep into our past.

For me, as someone rooted in anthropology, humanism, Stoic practice, and Nordic animism, these works are not static. They are alive — like songs or rituals — recalled, repeated, and reinterpreted. In an animistic worldview, these are not merely depictions of animals; they are animals. Beings. Spirits. Ancestors. Teachers.

This isn’t a metaphor. It’s a relationship — and one we are called to reawaken.

2. Why Portugal Matters

Portugal is home to one of the richest yet least globally recognized concentrations of Paleolithic rock art. The Côa Valley Archaeological Park contains over a thousand open-air engraved panels dating to the Upper Paleolithic. Unlike the cave paintings of Lascaux or Chauvet, these works are exposed to sun, wind, and rain — and still endure.

The Iberian Peninsula served as a glacial refugium during the Last Glacial Maximum (Carvalho, 2010), making it a stronghold for both human populations and artistic traditions. This continuity created a remarkably layered archive of expression.

Portuguese engravings differ in form and technique. They are etched, pecked, or abraded — their visibility shaped by natural light, weather, and time of day. Panels from sites like Mazouco and Fariseu often show overlapping generations of carvings, creating palimpsests that reflect a dialogue across centuries. The art isn’t only about what was carved — it’s about where, when, and how it was meant to be experienced.

In Côa, the land remembers.

Photo by Symeon Ekizoglou on Pexels.com3. My Path to Deep History

I grew up in California, captivated not by the landscapes around me, but by what lay across the Atlantic — the caves and shelters of Europe adorned with ancient marks. My first experiences with rock art were through books and digital reconstructions of sites like Chauvet and Altamira. Over time, I also gained exposure to Native American petroglyphs, developing a respectful and ongoing appreciation for their cultural significance.

Today, I’m pursuing my degree in anthropology at Arizona State University’s online program, with a focus on human origins and cognition. This academic path is deeply intertwined with personal philosophies — Stoic resilience, animistic reverence, and a humanistic commitment to empathy and understanding.

For me, studying Paleolithic art is not just academic. It’s personal. These marks challenge how I see the human story — not as a linear march of progress, but as a branching, spiraling chorus of memory, meaning, and imagination.

Moving to Portugal is a commitment. It’s a pilgrimage to the places where the first artists spoke, not in words, but in form and gesture. I want to be there — to learn not just with my mind, but with my whole being.

4. New Tools for Old Stories

The study of rock art has evolved beyond field sketches and measuring tapes. We now use digital tools and interdisciplinary techniques to uncover layers once invisible:

- 3D scanning and photogrammetry capture high-resolution digital models of rock surfaces, preserving them and allowing detailed study without physical contact (Domingo et al., 2015).

- AI and machine learning help identify stylistic groupings, iconographic themes, and even possible artist signatures by comparing motifs across thousands of images.

- Portable XRF (X-ray fluorescence) offers non-invasive chemical analysis, revealing what tools or pigments were used — even where color is no longer visible.

- GIS mapping places rock art in spatial context, revealing patterns in site placement, resource proximity, and astronomical alignments.

These technologies are not replacements for wonder — they are tools for amplifying it. They let us see what previous generations could only guess, and connect sites across time and space in new ways.

5. Why This Still Matters

We live in an era of distraction, where meaning is often commodified or fleeting. Paleolithic art reminds us of something deeper: that the urge to create, to symbolize, to remember, is foundational to being human.

These engravings are not idle doodles. They are necessities. They anchored social bonds, encoded cosmologies, trained memory, and marked place. They testify that survival alone is not enough — we need connection, story, and a sense of the sacred.

In our own time of ecological and existential crisis, these ancient marks offer a mirror. They invite us to slow down, observe, and listen. They show us that humanity has always sought to navigate uncertainty through imagination and shared symbols.

Interpretation requires humility. As Conkey (1997) reminds us, we may never truly know the minds behind these images. But listening itself is an act of reverence.

Listening to the Stones

When I arrive in Portugal, I won’t walk into a sterile lab or academic echo chamber. I’ll step into a valley sculpted by wind and river, by time and memory. I’ll stand where ancient artists once stood, tracing forms they carved by firelight.

They did not carve for us. But they carved with the hope, perhaps, that someone would follow. That someone would see. That someone would remember.

So that is what I intend to do: not to speak for them, but to listen.

ScreenshotReferences

Aubry, T., & Sampaio, J. D. (2008). Antiquity, 82(315), 1024–1037. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00097802

Carvalho, A. F. (2010). Quaternary International, 223–224, 254–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2010.02.011

Conkey, M. W. (1997). In L. Hager (Ed.), Women in Human Evolution (pp. 172–207). Routledge.

Domingo, I., Villaverde, V., López-Montalvo, E., de la Cruz, M., & Martínez-Vidal, A. (2015). Journal of Archaeological Science, 55, 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2014.12.010

Henshilwood, C. S., d’Errico, F., Yates, R., Jacobs, Z., Tribolo, C., Duller, G. A. T., Mercier, N., Sealy, J. C., Valladas, H., Watts, I., & Wintle, A. G. (2002). Science, 295(5558), 1278–1280. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1067575

Lewis-Williams, D. (2002). The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art. Thames & Hudson.

#AncientArt #Animism #Anthropology #ArchaeologicalResearch #Archaeology #CaveArt #CoaValley #CulturalHeritage #DeepHistory #HumanOrigins #OpenAirRockArt #PaleolithicArt #Pleistocene #PortugalArchaeology #PrehistoricArt #RockArt #ScienceCommunication #Stoicism #SymbolicThought