The thread about the Lochend Steel Houses; Edinburgh’s first – and controversial – steel suburb

There’s a quiet and well-kept little corner of the Lochend Housing Scheme that is a bit different from the rest. Its houses look distinctly municipal (although they were never “council”), but they are at a lower density than other parts of the scheme; there are bungalows and there are no tenements. You wouldn’t know it to look at it, but underneath the modern external insulation and pebbledash, all of these houses are steel houses. Lets find out how these houses came to be and what sort of houses they are.

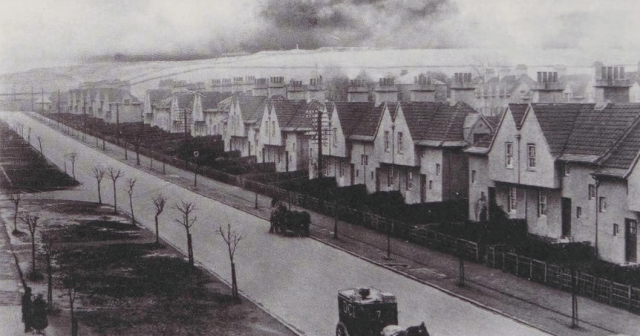

Lochend steel houses at Findlay GardensIn February 1926 the Scottish National Housing Company Ltd. (SNHC) formed a new subsidiary to provide 2,000 steel houses for Scotland; the imaginatively named Second Scottish National Housing Company (Housing Trust) Ltd., (SSNHCHT). The objective of this was to quickly build new housing in areas that needed it, without either making demands on the skilled labour market or the material supply of the traditional building trade; bricks, stone, plaster and cement. By producing the houses out of prefabricated steel components, idle engineering workers could be employed; unskilled workers could quickly erect the houses on prepared sites and there would not be a significant drain on building materials. A further consideration was that there was a deep recession in the Scottish shipbuilding industry, which was projected to last for some years further. By extension, this impacted the wider engineering, steel and coal industries, and Scotland’s industrialists and a number of politicians saw steel houses as a stimulus for these sectors.

The SNHC had been set up in September 1914 to built housing on land owned by the Admiralty adjacent to the new Rosyth Dockyard. Its stated objective was “to carry on the business of housing, town-planning and garden city making” i.e. to develop the Rosyth Garden City for let to dockyard workers. It was arranged along the lines of a public utility company, with dividend limited to 5% and a board stuffed with the worthies of local government of Scotland, including the Lord Provosts of Glasgow and Edinburgh. During the war, they would go on to build some 1,872 houses at Rosyth.

Rosyth Garden City, cottage houses, 1920The capital for the SSNHCHT steel house programme of the was provided by the government – 50% from the Public Works Loan Board and 50% from the Scottish Board of Health (at a rate of 5% interest, this scheme had to pay itself back!). Its time-scales were ambitious, with only 2 years were allowed to complete and there a £40 penalty for each house that failed to meet its scheduled delivery date. To keep labour demands down, only 10% of the workforce could be from the skilled trades, with penalties for exceeding this proportion. Houses were allocated to the main centres of population, including 750 for Glasgow, 350 for Edinburgh and 300 for Dundee. Five approved types were ordered; 1,000 Weir Houses (in 3 variants), 500 Atholl Houses and 500 Cowieson Houses. The SSNHCHT had to abide by local building regulations and have their proposals approved by the Dean of Guild Courts (the equivalent then of a planning committee). Rents were set to local equivalents and factoring was handled by local agents – in Edinburgh this was Gumley & Davidson. All of the steel houses had coal fires as the only source of heating and hot water and were lit by gas; electricity was ruled out as an economy.

Weir steel houses at Garngad in GlasgowSteel houses were not without controversy – indeed the government’s initial offer had been a £40 per house subsidy to local authorities that ordered and constructed their own such houses; none had taken it up, which was why they turned to the SNHC. The prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, had to intervene due to the controversy and made the provision of steel houses something of a campaign promise. Mrs Baldwin offered to personally live in one for a month to demonstrate how satisfactory they were.

The socialist movement faced the question of whether to resist them on account of their perceived lack of quality and the labour practices involved in their manufacture versus accepting them as a cheap way to quickly provide modern new houses for slum clearance. This caused a substantial rift at the time; John Wheatley MP (who as Minister of Health had been behind the “Homes for Heroes” council houses of the 1919 programme) spoke unfavourably of them: “the people [do] not want steel houses. [I have] yet to learn that a single one of the thousands who had bought their own houses had ordered a steel house“. The building trades were unhappy that workers employed in fabrication at the factories undercut their rates and that only 10% of the labour could come from their members. Mr Hicks of the Building Trades Union condemned them as “shoddy and insanitary“. His union was in turn accused of protectionism and of trying to prevent underemployed engineering workers and casual labourers from getting steady work on fabricating the houses.

There was also official prejudice against steel houses within Edinburgh; Baillie Mancor of the Town Council said the council wanted “real houses” and not steel houses; Councillor Mrs Eltringham Miller said that these houses were “a gift, and they were not looking forward to what they would cost after they had them.” Councillor Hardie went further and said that these were “shoddy building substitutes” and that the state was adopting a “Mussolini attitude” in forcing steel houses upon local authorities. Nevertheless, the Housing and Planning Committee approved sites in Edinburgh for the scheme on land they had already laid out for municipal housing. 250 were to go to Lochend, where 23 acres were transferred to the SSNHCHT and 100 to the Wardie district; additional land was reserved at Saughton as the Corporation desired 500 steel houses in total and was keen to encourage the SSNHCHT in any way it could.

Work progressed quickly; in July 1926 it was reported that “satisfactory progress” was being made and that the new houses were proving popular with applicants. By August, groundworks were complete and houses were beginning to rise from the ground; many more applications for let were being received every day. Rents were set at £22 per annum for cottage flats, £28/10 for the bungalows and £34 for semi detached houses. In November 1926, The Scotsman reported that the Lochend steel houses were nearing completion, with “quite a batch of Weir houses ready now, and men at work on the gardens, shovelling a rich, dark soil, which augurs well for the gardens of the future.” The paper observed that the houses were “more than empty: they have never been inhabited” and that it was with the “coming of the people and the gardens that they will acquire a personality.”

Lochend was allocated all 5 available types under the scheme, laid out in typical garden city style, the streets taking the name “Findlay” from John R. Findlay, Bt., chairman of the SSNHCHT (the steel houses at Wardie were given the streetnames “Fraser” from Provost Fraser of Dunfermline, who was on the board of directors).

Housing types and distribution of the Lochend Steel HousesAtholl Cottage Flat

These houses were produced by the Atholl Steel House Company and named after one of its founding partners, the Duke of Atholl, who had envisaged building a steel house in 1919 after touring the idle shipyards of the Clyde. He partnered with the industrialist William Beardmore, whose shipyard and locomotive works were desperate for work, with his steel foundry at Mossend in Lanarkshire ready to provide the plates. Also known as “4 in a block” houses, this style was very popular with the 1920s public housing schemes, offering a good balance between reducing building and population density, construction costs and giving each household its own entry door and garden.

The Atholl Cottage Flat. The house on the right has not been rec-lad, and the steel panel lines are visible. Like the Weir Lanefield, the upper flats were accessed through the side. The narrow central upstairs window is diagnostic when comparing it with the Weir Cottage Flats.Atholl’s original house was to be a lodge for his own estate, and as such was designed and built to be permanent. The construction of the Atholl House was therefore more substantial than its competitors, requiring 3 to 4 times as much steel. These heavyweight steel walls were load bearing, providing rigidity to the steel framework to which they were attached and therefore no internal cross-bracing was required. The steel was coated on its inner face with granulated cork to prevent condensation and then lined with composite boards, which were painted or wallpapered, eliminating the need for plasterers. Atholl estimated the lifespan of his house to be 60 to 90 years, with that of the Weir and Cowieson being 40 years.

The Weir Houses were produced by G. & J. Weir, engineers to the shipbuilding industry at the Holm Foundry in Cathcart in Glasgow. Weir’s chairman, Viscount Weir, had a particular interest in the idea of prefabricated houses and they would be something the company returned to on numerous occasions. Those of the 1926 scheme were of three distinct types, but all used the same basic structure, of a load bearing timber frame and floors to which a relatively thin skin of steel plates was attached as an external cladding. Their lighter construction and lower labour costs than other steel houses meant that they were the cheapest, and Weirs therefore got 50% of the total order for the scheme. A feature of all Weir houses was exposed internal copper plumbing; it could not easily be buried within the walls or their thin insulation layer, and Lord Weir felt it was better to make it accessible for repairs, so was simply clipped along the inner partitions. The Weir Paragon House of 1944 inherited this design feature.

General construction diagram of the Weir Steel Houses; a wooden frame sitting on a concrete base, with lightweight steel panels cladding the outside.In 1925, Weirs built a demonstration steel bungalow in Grosvenor Square in just 10 days:

10 days to complete a house. The Weir demonstration house in Grosvenor SquareThe Weir Houses were the most controversial of the steel houses as Weirs paid their workers at the rates of the engineering trades from which they were drawn, which were lower than those of the building trades. Weirs were accused of building “steel houses of a very inferior kind by paying low wages under sweated conditions“. In an editorial, The Scotsman called them “a pig in a poke” (an unknown entity) but that people would want to live in them anyway and prevailed upon Weirs to improve their wages. Atholl avoided this scandal by paying building trades rates to their prefabrication workers in the factories.

Weir Eastwood Bungalow

The correspondent from The Scotsman who was sent to review the house noted that “the Living room is a good size, and the kitchenette or scullery is larger than that of many a modern brick house. The two bedrooms are a sensible shape“. The Eastwood, like its siblings, featured lots of built-in storage cupboards and a built-in coal bunker in the kitchen. The price, excluding groundworks, was set at £365 per house.

Weir Eastwood Bungalow at Lochend, this pair of houses were in a very original condition at the time this photograph was captured.Weir Douglas Semi-Detached House

The Douglas was the largest of the Weir Houses and was a semi-detached, two-storey cottage house. The ground floor contained a sitting room with “handsome fireplace”, kitchen, larder, bathroom and – something of a novelty for the time – a large under-stairs cupboard. Upstairs were the three bedrooms, with the master bedroom running the full width of the house and having an unusually wide casement window to the front. This was the only house of the programme that had 3 bedrooms; all the other having 2. The price, excluding groundworks, was £390 per house.

Weir Douglas Semi. The house on the right is in a very original condition, that on the left has modern windows, roof, external insulation and cladding and porch. Note the five-pane first floor window.Weir Blanefield Cottage Flat

This was the cottage flat in the in the Weir range. It was basically a 2-storeyed version of the Eastwood Bungalow with the upper flats accessed by internal staircases accessed from the side. The upstairs kitchens had floors strengthened with timber laid on a damp-proof layer to protect the steel beneath from “the vigorous scrubbings” of the housewife. The price, excluding ground works, was set at £357 per house.

Weir Blanefield Cottage Flat. In a relatively original condition excepting the modern UPVC windows in 3 of the 4 flats. The easiest way to discern this from the Atholl cottage flat is the lack of the narrow central upstairs window to the front, and the upstairs outer window is offset somewhat from that on the ground floorCowieson Terraced House

F. D. Cowieson had trained as an architect, but found success in prefabricated wood and iron buildings, with the company based in St. Rollox in Glasgow. Initially these were simple agricultural structures such as barns and sheds, but soon the company was offering halls and huts, pavilions and even cinemas. During WW1 the company turned to building bus and lorry bodies – particularly ambulances – and they would later become much better known for this side of the business. They also experimented with “brieze block” houses, a single pair of which were trialled in Edinburgh at the Riversdale Demonstration Site.

1920s advert for Cowiesons, describing the range of prefabricated structures that the company offered.The Cowieson Houses built in the programme were of a four-in-a-block terrace and like the Weir Houses, used a load bearing wooden structure to which a steel cladding was applied. The roof was originally asbestos tiles.

Cowieson Houses at Lochend the three houses on the left have been re-roofed, externally insulated and pebbledashed; that on the right has not and looks to have its original roof also.Cowieson Houses in Dundee, built under the 1926-7 scheme by the SSNHCHT. This photo has been included as the exterior is in its original condition and the light paint shows up the steel panel lines to good effect.In July 1927, Lochend was proudly exhibited to King George V and Queen Mary, who made a royal visit on 11th of that month. Before proceeding to Lochend, the visitors stopped at the Corporation’s newest housing scheme at Prestonfield, where the King and Queen each planted a tree to inaugurate the development. They then headed to Lochend through the Holyrood Park, with 35,000 school children turned out to line the route. Further crowds greeted them at Lochend and they made a slow drive through the new neighbourhood, guided by Lord Provost Stevenson and two councillors.

Their majesties expressed pleasure at the fine layout of this garden city and were greatly interested in the many types of construction in evidence as well as the openness of the place and tasteful arrangement of the gardens.

Edinburgh Evening News, 11th July 1927

The Royal Party at Lochend Drive. The Queen is leading the King onto the pathway, lined with a neat picket fence.A halt was made at 49 Findlay Gardens, a Weir bungalow, where an inspection was made of the house occupied by the Hill family and their two young children. Mr Hill’s occupation was given as the manager of an egg merchant, T. Howden & Co., in Leith, which gives an idea of the sort of persons who were living in the houses. The residents were asked if the house had been cold in winter; yes it had been, but it was not now (it was July!). The next house to be inspected was the Atholl House of Mrs Wilson at 7 Findlay Medway, where they remarked on the sensible layout of the interior and were intrigued by a bed settee in the living room, the Queen sat on it and plumped up the cushions.

The householders were apparently not informed in advance that they were about to receive their guests and the first thing they knew was the knock on the door from the police. One of the housewives was reputedly peeling potatoes when they arrived and said of the Queen: “She’s a verra hamely lady” and that “Ye hav’na much crack for folk o’ that kind, and ye’re a bit tongue-tacket, but she was that kind and natural, and said everything was very nice“.

The King and Queen leaving 58 Lochend Avenue, an Airey tenement flatOn leaving the steel houses, the royal party then proceeded to some of the Airey Duo-slab houses; Mr & Mrs Galloway at 58 Lochend Avenue and Mrs Dickson at 34 Lochend Drive.

In the end, an additional 500 steel houses were erected by the SSNHCHT above and beyond its original target, taking the total to 2,252. All were completed by the end of 1928 and the stock, along with those at Lochend, was passed to the ownership and management of the Scottish Special Housing Agency in 1963 when it took over the assets of the Scottish National Housing companies. Although they were only given a 40-60 year lifespan by their builders, most were first refurbished between 1978 and 1983 and in 3 years time they will have their centenary. Nearly all are still standing and most have been substantially upgraded with external insulation and rendering, double glazing, central heating, new roofs etc. A handful remain in an earlier state, usually those that had been bought very early under “right to buy” legislation. The tenants of those that were not bought early campaigned to have them upgraded rather than demolished, and most of those were subsequently bought (it was not possible to buy a defective house).

If you have found this useful, informative or amusing, perhaps you would like to help contribute towards the running costs of this site – including keeping it ad-free and my book-buying budget to find further stories to bring you – by supporting me on ko-fi. Or please do just share this post on social media or amongst friends.

These threads © 2017-2025, Andy Arthur.

NO AI TRAINING: Any use of the contents of this website to “train” generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to generate text is expressly prohibited. The author reserves all rights to license uses of this work for generative AI training and development of machine learning language models.

#CouncilHousing #Edinburgh #GardenCity #Lochend #prefabrication #prefabs #publicHousing #Restalrig #SNHC #SSHA #SteelHouse