AI’s Evolution, Ethical Challenges, and Global Impact

Author(s): Scott Douglas Jacobsen

Publication (Outlet/Website): The Good Men Project

Publication Date (yyyy/mm/dd): 2025/05/09

Neil Sahota, an IBM Master Inventor and AI expert, discusses AI’s rapid evolution, applications, and ethical challenges. He explains AI as a “high-energy intern” that learns from data rather than following rigid programming, differentiating it from traditional software. AI’s ability to process natural language enables contextual understanding. Still, there are many misconceptions, including fears of AI replacing jobs when, in reality, humans using AI will replace those who do not. Sahota highlights the global AI race, particularly between China and the U.S., and the importance of proactive AI governance in addressing these concerns. He emphasizes the role of hybrid intelligence, where AI complements human strengths, as seen in law, healthcare, and education. Countries like the UAE and Singapore are leveraging AI for workforce transformation. Sahota warns of AI’s dangers, including the lack of explainability in decision-making, and stresses the need for ethical frameworks to ensure responsible innovation.

Scott Douglas Jacobsen: So, we’re here with Neil Sahota. He is an IBM Master Inventor, AI advisor, AI expert, and co-author of Own the AI Revolution. He is also a faculty member at UC Irvine. I’ve done three years of fellowships at UC Irvine, so go Anteaters.

He has over twenty years of experience driving innovation across healthcare, legal services, and telecommunications industries. He has advised startups, venture capital funds, and investment groups such as Tech Coast Angels and Passion for Social Impact. He also supports nonprofits like the Zero Abuse Project and Planet Home, which are organizations leveraging AI and emerging technologies to drive business growth and sustainability. His work bridges technology, entrepreneurship, and social impact, making him a recognized leader in AI innovation. So, thank you for joining me today. I appreciate you taking the time.

My first question is about AI. We have science fiction representations of it and popularizers discussing concepts like the law of accelerating returns, exponentials, and scaling laws. We see public tensions between Sam Altman and Elon Musk, primarily with Musk criticizing Altman. We also observe global competition for AI dominance, particularly between China and the United States.

It’s a complex landscape, but many discussions make broad assumptions. Can you unpack what we mean when we say “AI”? What are some common myths, and what is the reality?

Neil Sahota: That’s a great place to start.

First, there is no universally accepted definition of AI, which is part of the challenge. The United Nations and many AI experts generally define AI as a system that can perform tasks requiring cognition without direct human supervision.

So, when we talk about AI, I like to call it a high-energy intern.

You don’t program AI in the traditional sense. Unlike conventional software, AI doesn’t follow a rigid set of pre-defined instructions. Instead, we teach AI—this is where machine learning comes into play.

We provide AI with something called ground truth—guidelines on how to make decisions, but not the decisions themselves. We give it vast amounts of data and human feedback, and that’s how it learns—and it learns fast.

The second key point is that AI understands natural language. Most people don’t speak in perfectly structured sentences—we use slang, idioms, and jargon. AI is different from traditional search engines, which rely primarily on keywords.

For example, if you type into Google, Show me restaurants, but not pizza, it might still show you pizza places.

AI, on the other hand, has contextual understanding. It processes grammar, syntax, and meaning, recognizing that not pizza means it should exclude pizza-related results.

So it understands how we speak. Then there’s the conversational aspect, which is more of a back-and-forth. It’s almost like I’m talking to a human. I can have a persistent conversation, whereas more traditional software search engines don’t remember the last command that we put in. So, that’s what we call AI.

Now, there is much hype regarding reality versus hype. There is no one mega ChatGPT, for example, that knows what a billion users are doing. There are several hundred billion instances of ChatGPT. You pay for ChatGPT to have your private instance.

There are multiple versions of it with different knowledge and capabilities. There isn’t one uber version. That’s the biggest misconception people have, which is ironic, given data privacy and security concerns. People expect that AI already knows how to do things, but that’s not the truth. Unless you’ve taught the AI how to do it and trained it on your processes and data, it doesn’t know how to do that work.

That’s why I always say it’s a high-energy intern. It’s ready to do whatever you want, but you must teach it. That’s the key thing. AI can only do what we can teach it. That’s why it’s good at reading through documents, detecting money laundering, helping plan vacations, or analyzing symptoms a person is showing—or not showing—to assist doctors and nurses with diagnoses.

But we can’t do things like reading brain waves. We don’t fully understand how that works as humans, so we can’t teach AI. That’s the line between hype and reality.

Jacobsen: Now, when it comes to the United Nations and AI ethics, how does AI ethics build into international frameworks? How can we guide the development of this technology when we strip away the myths and deal primarily with reality?

Sahota: I’ve been a big proponent of the idea that bad actors do bad things, but good actors need a nudge.

Historically, there has been much investment in AI, and businesses naturally think about the return on that investment, which makes sense. But from a societal standpoint, there’s often been this divide—profit versus nonprofit—not recognizing the intersection between the two: social enterprise.

That’s one of the reasons I worked with the United Nations to co-found the AI for Good initiative.

First, it’s about creating that nudge for good actors. Second, we don’t set guidelines or establish frameworks for AI ethics. In that case, people won’t consider these issues.

Historically, there has been an assumption that smart technologists—software engineers and roboticists—consider these ethical implications. But often, they don’t. They focus on what we call nonfunctional requirements (NFRs)—things like security, performance, and privacy. They build to technical requirements and design to specifications, but these NFRs often get overlooked unless they are explicitly addressed.

So, as a result, what tends to happen is that they build designs to achieve specific outcomes, but they don’t think about other possible uses or misuses.

Take drones, for example. When they first came out, the idea was that they could be used for land surveying, inspecting dams for damage, or performing other efficiency-related tasks in difficult-to-access areas. No one initially considered the potential risks—like someone flying a drone near an airport or into someone’s backyard to take a video of their child playing.

That’s the challenge we face—as a society, we’ve always been reactive.

When something bad happens, we analyze it, regulators step in, and we try to put safeguards in place so it doesn’t happen again. But AI has triggered the Fourth Industrial Revolution, and things are moving at a pace we call hypercharge.

We’re experiencing a hundred years of change in just ten years.

We don’t have time to be reactive anymore. By the time something bad happens, it could have already affected tens—if not hundreds—of millions of people. So, we must improve our proactive thinking. That’s one of the things we’re working on at the United Nations—fostering a mindset that encourages anticipating risks before they happen.

With AI governance, one of the ongoing discussions involves creating a consortium and a database to track potential uses and misuse of AI. But AI itself has a unique superpower that helps us in this effort.

First, AI is great at scenario planning.

Second, AI is the only tool that allows us to ask it:

“How can we use you better?” or “How might others misuse you?”

Our ability to think proactively is assisted by AI itself.

It’s a double-edged sword—depending on the intent of the person using it, technology can be used for good or harm.

However, the ultimate goal is to create that nudge for good actors and drive more positive innovation, particularly around the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Jacobsen: Regarding AI and ethics, the UAE, particularly Dubai, is one of the leading technology hubs in the world, especially within the MENA region.

This is something we see worldwide. For example, Dubai is developing flying taxis and integrating technology into snowboarding, skiing, and other recreational industries. Despite stereotypes, the UAE is a very tech-friendly place.

So, when we look at regions with huge capital flows that are not traditionally associated with AI, how do international AI ethics frameworks fit?

Are there specific governmental institutions, demographic considerations, or conflict dynamics within the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region that make applying AI ethics easier or more difficult?

Sahota: That’s a great question, Scott, and the answer is—it’s both easier and more difficult. It’s a weird dichotomy, to be honest.

It makes things easier because so many people are now using AI technology—even in the first wave of adoption—that they’ve at least been exposed to both the good and the bad. They’ve seen the potential for great benefits and the risk of great harm. That has led more member nations, government agencies, and private companies to discuss where to draw the boundaries.

From that perspective, it has become easier to have these conversations.

When new technologies emerge, there has always been tension between innovation and regulation. But now, more people recognize that we must invest in these discussions and figure things out before it’s too late.

Where it becomes difficult is agreeing on what is right.

What does right use even mean?

Take China, for example. There, police officers wear AI-powered smart glasses—ironically made by Google—that allow them to scan a person’s face and immediately see their name, home address, workplace, and location history for the last two hours.

On the one hand, this is incredibly effective for law enforcement—it helps locate criminals and missing children much faster.

But then, of course, you have to think about the nefarious possibilities of such surveillance.

From a Chinese cultural perspective, they may view this as a positive tool for public safety.

Meanwhile, in many Western countries, people would call this too much like Big Brother—an extreme invasion of privacy.

And that’s the real challenge in the digital age—no borders.

Nothing prevents people from using the same technology in completely different ways in different parts of the world.

So when we talk about “right use,” the real question becomes:

Do we need a global standard or baseline for morals and ethics?

That’s a visceral issue because it’s deeply personal to people.

I remember speaking at the Global Symposium for Regulators back in 2018. They asked me to give a speech, and that was one of the key points I raised.

I said:

“If we’re trying to establish the right guidelines and guardrails—not just for AI, but for all emerging technologies—we must agree on what ‘right use’ means.”

I threw a hand grenade into the conversation.

Everyone knew it needed to be addressed, but no one wanted to talk about it.

When I finished my speech, no one applauded. No one looked happy.

One of the Deputy Secretary-Generals (DSGs) walked up to the stage and said:

“Neil, that was a brave thing to say. It was the right thing. But you didn’t make any friends. You should leave now.

So, I did.

But what surprised me?

They invited me back the next year.

But then you start seeing these hallway conversations about it. Ironically, I was asked to come back last year at GSR, and they started calling me Firestarter. They didn’t understand at first, but then Doreen Bogdan-Martin, the Secretary-General of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), told me, “A lot of this year’s GSR agenda is based on that speech you gave.”

So, just having those hallway conversations helped spark something—they made people realize the need for these discussions about how we define right use and misuse. It’s easy to say, “If it helps people, it’s beneficial. If it harms people, it’s bad.” But in reality, there’s a lot more nuance.

Take the China example—that’s the kind of struggle we see. We recognize that different cultural perspectives must be brought to the table. Seeing more engagement from the EMEA region—the Middle East, Africa, and parts of Europe—is encouraging because they’re bringing their own priorities and insights. We’re seeing strong participation from the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Kenya, and Uganda.

And they’re raising a critical issue: If this is another kind of digital race, it’s exacerbating the digital divide between the haves and the have-nots.

This AI race isn’t just about who develops the best models—it has ripple effects. We’re now seeing a global scramble for rare earth metals to build the next generation of AI hardware, and even space exploration is being driven by the search for more of these resources. That’s creating a new divide between nations with strong R&D capabilities and those without.

So now, the discussion isn’t just about the ethical use of AI—it’s about the infrastructure needed to support it. Think about GPUs (graphics processing units), 5G, and soon-to-be 6G speeds—these are essential for AI to function. But they also introduce economic and geopolitical tensions. So, AI ethics must include discussions about who controls the infrastructure.

Jacobsen: So even if AI is doing 99% of the computational analysis, what are the things that will still require human input?

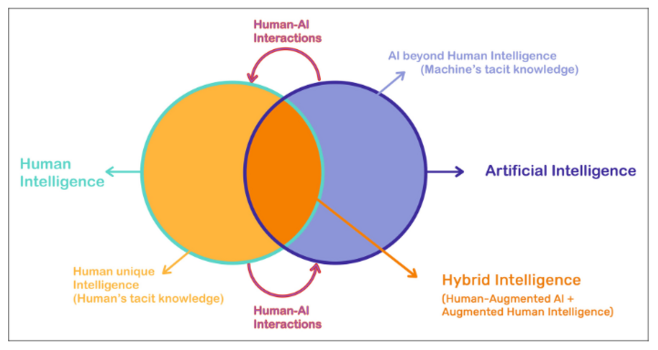

Sahota: A lot. People forget that while machines excel in certain areas, there are still many things humans are fundamentally better at.

AI struggles with first-of-a-kind tasks requiring imagination, creativity, or drawing completely new insights. Those are human strengths—and machines cannot replicate them. And the goal here isn’t to replace people. I know that’s a big fear, but the truth is: It’s not AI replacing people—it’s the person using AI who is replacing the person not using AI.

I’ve worked with dozens of institutions, companies, and government agencies that hoped AI would reduce headcount. But 95% of the time, that didn’t happen. They found that automating some of the administrative grunt work freed people to focus on higher-value, complex tasks.

Let’s take the legal industry as an example—since it plays a central role in government regulations and is the second slowest-moving industry I’ve ever seen.

Three lawyers founded a company called Legalmation. They weren’t technical experts but wanted to build a tool for their firm. They asked themselves: What’s something standardized and simple we can automate? Since they were defence litigators, they created an AI associate lawyer to handle complaints—the initial legal filings when someone is sued.

They built an AI system to read the complaint, fill out the corresponding court documents, generate a counter-complaint, draft deposition questions, and conduct initial case research. What previously took a human associate lawyer with three years of experience, about 10 to 12 hours, now takes just two minutes.

A human lawyer still reviews the AI’s work, spending 30 to 45 minutes fixing gaps or errors. But instead of eliminating jobs, they found that they could repurpose their associate lawyers to focus on more valuable work:

- Jury selection

- Spending more time with clients

- Practicing legal arguments

- Collaborating with co-counsel

- Developing case strategies

- Building business relationships earlier in their careers

These are all far more valuable to a law firm than spending hours on administrative tasks.

And that’s what we’re seeing across the board.

This is one of the biggest reasons we’re witnessing explosive AI growth in the UAE, Middle East, and Africa. AI is giving these regions a leapfrog moment, allowing them to radically upskill their workforce and reshape industries.

When discussing AI in the workplace, it’s not about humans versus machines. It’s about humans using machines—what we call hybrid intelligence. That’s the real future of work—leveraging human strengths while augmenting them with AI capabilities. That’s what’s amplifying innovation right now.

Jacobsen: What do you think is the real promise of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region for AI? And how have communities, demographics, and governments decided to organize themselves locally, nationally, and regionally?

Sahota: Well, one of the other things I always say is: Local problems have global solutions. And the work happening in MENA reflects that. For example, the UAE developed the Falcon platform because it needed AI tools that could understand Arabic, a language spoken by hundreds of millions of people.

They built their own AI models—including an Arabic version of ChatGPT—to address local linguistic and cultural needs. That’s exactly the kind of innovation we need. It’s a great example of how we can build AI solutions tailored to different languages, regions, and specific needs.

The second major area where AI impacts the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is health care and education, particularly through AI-driven tutors. However, one issue many people don’t realize is that some parts of the Middle East have high unemployment rates, especially among young people.

There’s a cultural and economic push for young people to pursue master’s degrees and Ph.D.s—and many do—but there still aren’t enough high-quality jobs for all of them.

By investing in AI, EMEA countries are not only diversifying away from oil but also creating entirely new job sectors. This enables highly educated individuals to apply their skills in AI-related fields and industries that didn’t previously exist in the region.

It’s another great model for future work that embraces hybrid intelligence and provides a template for other member nations and regions to follow.

This is important because we tend to focus on big tech companies and superpower countries when discussing AI. However, EMEA proves that with enough investment and support—from other member nations or the UN—almost any country can build its own AI ecosystem.

And that’s the baseline we need to get every country to—a place where they have the foundation to develop AI solutions for themselves and their communities.

Jacobsen: What are the perils of AI?

Sahota: Well, there are a few. Let me talk about some of the biggest ones.

One of the most fundamental challenges is human nature—and the reality is that an AI arms race is happening right now.

Just like we’ve had tech arms races in the past, nations and corporations are now competing for AI dominance. And as much as we’d like to believe that everyone is working for the greater good, there are always casualties in a competition like this.

The mistake is thinking of AI as a winner-takes-all game—as if there’s a fixed pie where one group has to take less so another can take more. But that mindset is creeping in, so the things we prioritize are not always the best choices. Sometimes, we sacrifice ethical considerations or rush developments to stay ahead in the race.

The second major peril, and honestly, the one that freaks me out the most, is that we are reaching a point where many people working on AI don’t fully understand what they’re building anymore.

The most successful AI solutions come from domain experts—for example:

- Legal AI should be developed by lawyers, paralegals, and legal professionals.

- Health AI should involve doctors, nurses, and clinical researchers.

- Marketers and data analysts should guide marketing AI.

However, too many people still believe technologists should dictate how AI is built and applied. As a result, we see a flood of tech startups led by engineers and developers trying to solve problems they don’t fully understand—problems they assume exist but often don’t.

And as a result, you end up with AI systems that don’t do what they’re supposed to do.

Take Facebook’s AI advertising system, for example. About a year and a half ago, they rolled out an AI-driven ad placement system and got busted for redlining.

Now, redlining refers to an illegal practice where certain demographics are excluded from opportunities—typically housing or financial services—based on race, ethnicity, religion, or sex. In the U.S., the Fair Housing Act explicitly prohibits this kind of discrimination.

But here’s what happened: People listing housing ads through Facebook trusted the AI to find the right audience. Instead of marketing to everyone, the AI intentionally excluded certain demographics based on its own learned associations.

So when Facebook was caught and fined, it returned to its engineers and asked, “Why didn’t you account for redlining when training the AI?” And the engineers said, “What’s redlining?” That’s exactly the kind of thing that worries me the most.

People build AI models without fully understanding the industries or social systems they affect. We see similar issues in generative AI (GenAI), especially in business applications. People write prompts but don’t understand all the parameters that influence the model’s outputs.

It used to be good enough to get a roughly accurate result, but now, “good enough” is no longer good enough. For example, my friend LJ Rich, a musician, has used AI for years to help compose music. She uses custom-built AI for melody generation, and her prompts are 500 words long.

She considers every detail—which notes to use, in what order, what harmonies to apply, rhythm, style, and other musical parameters.

We’ve discovered that even people who have worked in their fields for decades don’t always know all the parameters involved.

So, if experts in their industries don’t know the depth of AI models, how can technologies do it?

This leads to two major technical challenges in AI:

And unfortunately, most companies aren’t parenting transparency.

Some of this could be solved by using explainable AI, which we did with IBM Watson. We made sure that Watson could explain every conclusion it arrived at.

But the problem is, most AI companies don’t bud on this. They see it as extra work, administrative overhead, and something that reduces ROI.

So, those are two of the biggest AI perils that must be addressed.

Jacobsen: We always hear about Sam Altman, Elon Musk, and Eric Schmidt—the figures who dominate the news cycle about AI. But in your opinion, who are the real AI leaders internationally— particularly in the Middle East?

Sahota: That’s an interesting question because it depends on which part of AI you’re talking about.

There are many different flavors of AI, including visual recognition, natural language processing (NLP), large language models (LLMs), small language models (SLMs), and more. Different leaders and organizations are excelling in different areas. No leader is necessarily better than the others, but there are key figures in different areas of AI development.

For example, you have Geoffrey Hinton, often called one of the godfathers of AI, and Fei-Fei Li, considered one of AI’s godmothers—both played pioneering roles in shaping modern AI.

Then, major AI initiatives in China have brought in new power players. I remember being at the groundbreaking ceremony in 2016 for what they called “Future “ci-Tech City.” It was “designed to be a hub for emerging technologies, with dedicated AI and blockchain zones and massive investments in startup companies from around the world.

As a result, many influential AI figures don’t have names, but they’re the future of AI nonetheless. When we talk about power players, here are a few people who often fly under the radar:

- Omar Sultan Al Olama – Minister of AI, Digital Economy, and Remote Work Applications for the UAE. He’s one of the few government officials worldwide with AI as a direct portfolio.

- Madeline Bell is the CEO of ChildrenChildren’sl of Philadelphia (CHOP). She has been a major force in using AI for medical intelligence, particularly in pediatrics.

- Tara Lyons – Global Head of AI Policy at JPMorgan. Unlike the U.S.-centric approach to AI regulation, she focuses on international AI policy and how financial systems interact with AI globally.

- Kenichiro Yoshida is Sony’s CEO. He’s not only integrating AI across Sony’s lines but also rethinking how AI transforms the consumer experience.

Then you have governments making bold moves in AI:

- Singapore – They started major AI investments in 2016 after realizing how transformational AI would be.

- They launched workforce retraining programs for both current and future workers.

- They even set up public education initiatives to help consumers distinguish real AI from hype and make smarter decisions about buying AI-driven products and services.

And, of course, China has made AI a national priority:

- Xi Jinping—As President of China, he has embedded AI into the “Made in China 2025” strategy.

- He has directed massive investments into AI at provincial and national levels.

- The government has funded AI research hubs, infrastructure, and startup ecosystems, positioning China as a global AI superpower.

A lot is happening in AI, and while Altman, Musk, and Schmidt dominate the headlines, many other leaders worldwide are shaping the future of AI in meaningful ways.

Sahota: There’s HarshThere’ sn, the Minister of Health in India, and they’ve been working on raising the quality of rural hospitals to match urban hospitals. They have an incredible amount of data—over half a billion people—which they use to improve healthcare outcomes nationwide.

Jacobsen: Do you have any final thoughts based on our conversation today?

Sahota: It’s an interesting time, Scott. I wouldn’t dispute that.

It’s one of the tIt’s moments where, to borrow from Stan Lee and Spider-Man, “With great power comes great responsibility.” One of the “things I always emphasize is the three pillars of change: people, process, and technology.

When you change one, it triggers a shift in the other two. People are starting to realize that when they introduce AI tools into their workflows, they must also change their processes. This isn’t about it. It’s a new way of doing things. That’s the deThat’son of innovation.

However, the part where many people struggle is the people aspect. It’s not just training or retraining workers—it’s about changing our mindsets about how we think about and use these tools. A simple example is education.

We still teach using 19th-century techniques because they work well enough. But we now know there are better ways to wire our brains—through learning algorithms, cognitive science, and AI-driven teaching methods.

The problem is that we don’t leverage innovations because people think, “Why fix some thing that isn’t broken? Isn’t this “about isn’t something is broken? ” The real question is: Is there a better way of doing it? You can’t continue to improve a candle and expect to arrive at a light bulb.

To make that next leap, we must shift from reactive to proactive thinking. We need to anticipate uses and misuses before they happen—that’s why there are general concerns about AI and emerging technologies.

Jacobsen: Thank you so much for your time today.

Sahota: I hope it’s useful. I’m looking forward to seeing what you write. If I can ever help in the future, please let me know.

Jacobsen: I appreciate it, man. Thank you so much.

Sahota: You take care. Bye.

Jacobsen: All right. Have a good one.

Last updated May 3, 2025. These terms govern all In Sight Publishing content—past, present, and future—and supersede any prior notices. In Sight Publishing by Scott Douglas Jacobsen is licensed under a Creative Commons BY‑NC‑ND 4.0; © In Sight Publishing by Scott Douglas Jacobsen 2012–Present. All trademarks, performances, databases & branding are owned by their rights holders; no use without permission. Unauthorized copying, modification, framing or public communication is prohibited. External links are not endorsed. Cookies & tracking require consent, and data processing complies with PIPEDA & GDPR; no data from children < 13 (COPPA). Content meets WCAG 2.1 AA under the Accessible Canada Act & is preserved in open archival formats with backups. Excerpts & links require full credit & hyperlink; limited quoting under fair-dealing & fair-use. All content is informational; no liability for errors or omissions: Feedback welcome, and verified errors corrected promptly. For permissions or DMCA notices, email: scott.jacobsen2025@gmail.com. Site use is governed by BC laws; content is “as‑is,” liability limited, users indemnify us; moral, performers’ & database sui generis rights reserved.

#AIEthics #ethicalFrameworks #globalCompetition #hybridIntelligence #proactiveGovernance