Hunter-gatherers made this?! 🤯🤔

What really puzzles me is the disbelief that hunter-gatherers somehow could be capable of cultural achievements.

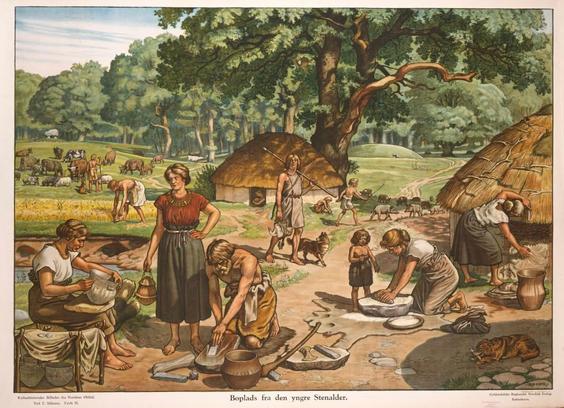

Does this come from an outdated idea equalling #HunterGatherer with #primitive?

🧵 A fundmental misunderstanding ...