What we learned this week

With Just Stop Oil calling it a day in the UK, saying their mission has been achieved, now Last Generation have turned off the lights in Germany. It feels to me like the closing of a chapter of civil disobedience for the climate.

The Climate Coalition are organising another mass lobby of parliament, their biggest yet, on the 9th of July. Register here for Act Now, Change Forever.

Analysis of the current UK heatwave from World Weather Attribution has found that climate change has made these June temperatures 100 times more likely. 32 degrees in June occurred “only once every 2500 years before industrialisation.”

I found myself on a particularly noisy station platform in London recently, which reminded me of this video on noise pollution and urban design. There are techniques for reducing noise in cities if we choose to use them.

Teacher friends, Let’s Go Zero have a week of climate action for schools starting on Monday, with lots of resources and activities to bring into your classrooms.

Power Station trailer

I’ll come back to this in more detail when I’ve seen it, but the documentary Power Station had its premiere yesterday at the Sheffield Documentary Festival and the official trailer has been released. I’ve met the film makers a couple of times and have been following the story as they try and put solar panels on every house in their London street, turning their neighbourhood into their own power station, with their signature brand of homespun radicalism.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TaoJzRiZ25s

Latest articles

Celebrating 25 years of the Ashden Awards

The Ashden Awards were held last night, marking 25 years of the awards for climate innovation. To mark the occasion, four previous winners were honoured with outstanding achievement awards, in a ceremony presented by Myra Anubi, with special guests Vanessa Nakate and UK Climate Envoy Rachel Kyte. Two new winners also took home awards, Emergent…

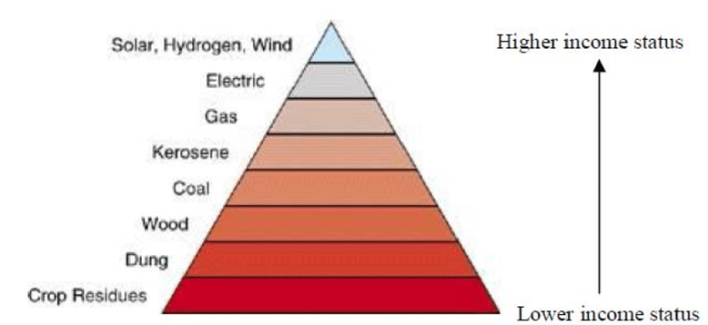

by Jeremy WilliamsJune 12, 2025Climbing the energy ladder with BURN

At the Ashden awards last week, BURN won the Award for Outstanding Achievement. It’s a special category in honour of the 25 anniversary of the awards, given to a previous winner who has gone on to do extraordinary things. BURN make affordable cookstoves which save families money, reduce indoor air pollution and help to protect…

by Jeremy WilliamsJune 19, 2025Book review: Deficit, by Emma Holten

In 2020 Emma Holten read an article in the Danish press that argued that over the course of their lifetimes, women took more from the public purse than they gave. This made them a net deficit to society. Holten took umbrage at the idea, quite rightly, and borrowed the word as the title of her…

by Jeremy WilliamsJune 11, 2025June 7, 2025