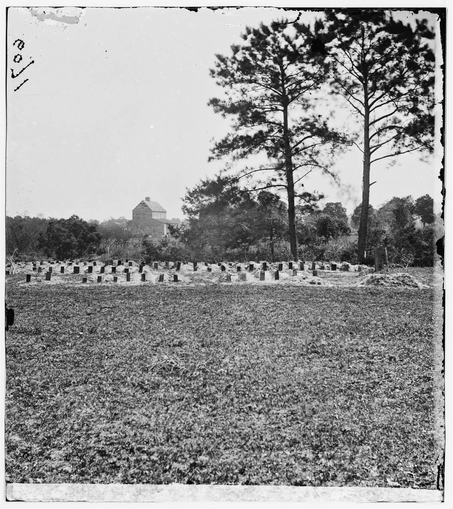

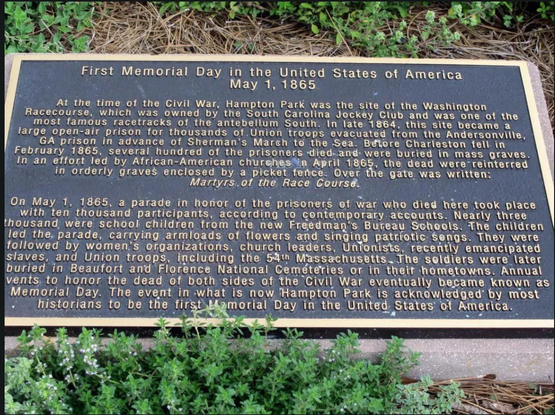

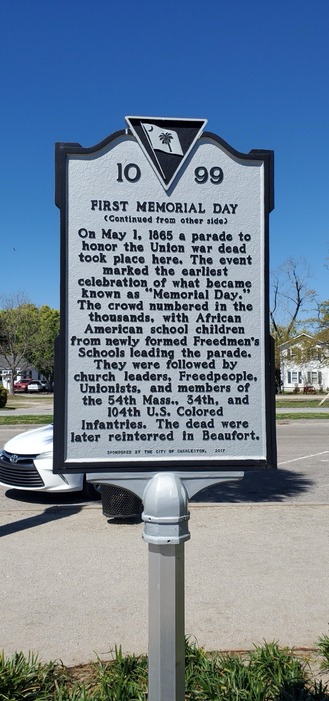

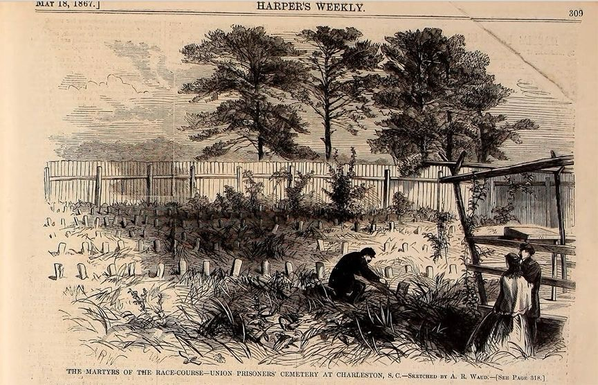

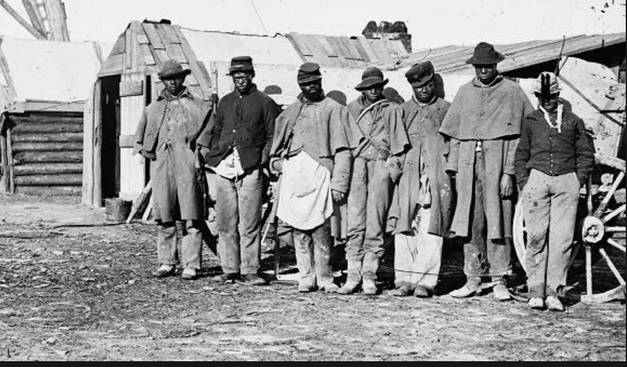

They came with roses. With hymns. With children.

It was the 1st Memorial Day.

But America gave the credit to others & buried the memory.

#MemorialDay #History #Histodons #Politics #photography #blackandwhite

#blackmastodon

#blackandwhitephotography

1/21

Image: Black American Civil War Memorial, Spirit of Freedom statue by Ed Hamilton 1997, NPS, Washington DC.