JUNE 1944

Excerpt from the Circular of Mother Agnès of Jésus

The war is hanging over our Normandy. The air raids intensify. Great anguish embraces our hearts, facing a terrible unknown.

On the evening of the 6th, a first bombardment fell on the city, shaking the walls of the Monastery and foreshadowing a continuation.

All night long, our beloved Mother was sheltered, with part of the Community, in the infirmary where Sister Marie of the Sacred Heart had died; the bombs rained down around us because our improvised shelter was just near the string of missiles that had been fired on the street in front of our Carmel.

Grouped together next to our valiant Mother, terrified, we prayed with her, and she remained calm; to see her, to experience ourselves alongside her was our strength. But as soon as there was a lull, she rushed to the Turn to ask for news of the terrible drama.

The next morning, Monsignor Germain, Director of Pilgrimages, came to the sacristy and offered to give us Holy Communion, because the situation was too insecure for us to celebrate Holy Mass. The chaplains’ house was no longer fit for habitation, and the house of our Sisters of the Carmel Saint Joseph, adjoining us, had partially collapsed.

The city was an immense inferno, there were more than one thousand victims; all the reports that reached us were distressing. The population fled to the surrounding countryside, because another bombardment, we were told, had been expected for the beginning of the afternoon.

This time, we wanted to take refuge in the other wing of the convent, in the Infirmary of our little Saint. But unaware of the danger, and faithful to her duty, our Mother lingered and one of us had just enough time to take her in her arms to huddle with her in an apartment when the deluge of bombs surrounded us again.

Our courtyard disappeared under an acrid and yellowish smoke. We got out of it unscathed, but what were our prospects for the next night? Just a few days earlier, Mother Agnès of Jesus confided:

“I’ve made the sacrifice of our little Carmel to the good Lord if he wants it!”

Carmelite Nuns of Lisieux

Excerpt from the obituary notice called a “circular”, that was written by the nuns for the other Carmels in France and across the Order. A separate English obituary also was prepared, which is not a strict translation of the French text.

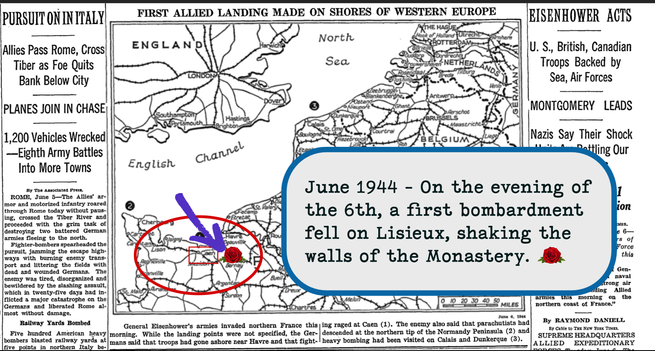

Lisieux after the bombing raids of June 1944. The Basilica of St. Thérèse is seen in the background. Photo credit: PhotosNormandie / Flickr (Some rights reserved). Visit their Lisieux photo album for more images of the city in June 1944.In the featured image, we see the front page of The New York Times on Tuesday, June 6, 1944, which was a map of the invasion sites below the headline: ALLIED ARMIES LAND IN FRANCE IN THE HAVRE-CHERBOURG AREA; GREAT INVASION IS UNDERWAY.

The caption underneath the map says:

“General Eisenhower’s armies invaded northern France this morning. While the landing points were not specified, the Germans said that troops had gone ashore near Havre and that fighting raged at Caen (1). The enemy also said that parachutists had descended at the northern tip of the Normandy Peninsula (2) and heavy bombing had been visited on Calais and Dunkerque (3).”

Although the New York Times map does not indicate by name the location of Lisieux, it is southeast of Deauville on the railway.

Military scholar Dr. Stephen A. Bourque provides additional detail concerning the June 6 Allied bombing raid on Lisieux in his article, “Operational Fires Lisieux and Saint-Lô – The Destruction of Two Norman Towns on D-Day.” In this excerpt from the 2010 article in the journal, Canadian Military History (Vol 19, 2), Professor Bourque explains the reason for the terror described by the nuns.

Before the sun came up, reconnaissance units from the 12th SS Panzer Division passed through the centre of [Lisieux], heading west toward the sounds of the fighting. Unit commanders noted the citizens’ apparent calm, and, in spite of the obvious sounds of war, they appeared to be beginning the day as if it was just like any other.

The rumble of battle continued all morning and Allied aircraft seemed to be everywhere above the clouds. No one on the ground realized that at 0900 hours 81 B-17 Flying Fortress aircraft were overhead and prepared to drop their bombs on the city. The bombardiers, however, could not locate their targets through the cloud cover and turned back to England.

As the morning turned into afternoon, the citizens heard less from the beaches, and the firing was not quite as loud and more intermittent. Allied aircraft, primarily fighter-bombers, flew over the town and sometimes machine-gunned the German convoys along Route 13.

Watching these events, the citizens now waited with foreboding that the cannonade would surely come their way. Allied commanders were not happy that the main east-west highway was still open on the afternoon of 6 June. They knew that the 12th SS Panzer was on the move and that Hitler had ordered SS General Joseph (Sepp) Dietrich, commander of the 1 SS Panzer Corps, to throw the invaders “back into the sea.”

Determined to stop German units from heading to the front, they directed the bombers to repeat the aborted mission again and to strike Lisieux before sunset. Around 2000 hours, 72 B-24 Liberators crossed the English Channel and flew towards the city.

This time, since the leaders expected that the cloud cover would prohibit any precision, they ordered the crews to use “overcast bombing techniques,” a euphemism for area bombing, without regard to either accuracy or civilian casualties. To make accuracy more problematic, increasingly bad weather forced the aircraft to fly higher than anticipated, now up to 23,000 or 24,000 feet. Still, many aircraft were unable to find either this or any target, and headed back to England.

However, 25 B-24s fought through the weather and headed for Lisieux intent on dropping their 73 tons of explosives on their assigned objective. At 2020 hours, the Liberator squadrons appeared over the city centre and began dropping their munitions, just as the citizens sat down for their evening meals and young children went to bed. The streets were empty, as the evening curfew had just taken place, and almost everyone was at home.

Bourque, S 2010, ‘Operational Fires Lisieux and Saint-Lô – The Destruction of Two Norman Towns on D-Day’, Canadian Military History, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 29–30.

The New York Times 1944, First Allied Landing Made on Shores of Western Europe, The New York Times, viewed 5 June 2024, <https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1944/06/06/issue.html>.

Translation from the French text is the blogger’s own work product and may not be reproduced without permission.

https://carmelitequotes.blog/2024/06/05/lisieux6jun44/

#bombingOfLisieux #CarmelOfLisieux #DiscalcedCarmelites #fearless #history #inspiration #monasticLife #MotherAgnesOfJesus #Normandy #nuns #sacrifice #WorldWarII