Telehealth interventions for managing #multimorbidity can be cost-effective and improve access and health outcomes in rural and remote areas. This #ScopingReview (n=15) stresses variability in findings and need for standardised implementation:

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/26335565251344433

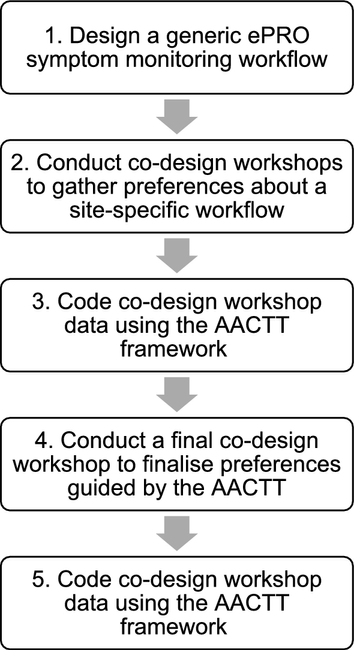

A new paper discusses workflow development for ePRO symptom monitoring to support PRO(M) implementation into practice using the Action, Actor, Context, Target, Time framework:

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11136-025-03995-y

#HRQL #PatientCentered #ImplementationScience #ParticipatoryResearch

Customizing workflows for electronic patient-reported outcome (ePRO) symptom monitoring using the action, actor, context, target, time (AACTT) framework - Quality of Life Research

Background Real-time electronic patient-reported outcome (ePRO) symptom monitoring is a complex intervention with few examples of successful implementation at scale. A key challenge is designing a clear ePRO symptom monitoring workflow to support implementation into practice. We aimed to create an empirical and theory-informed site-specific workflow guided by the Action, Actor, Context, Target, Time (AACTT) implementation science framework. Methods A five-step process was undertaken to customize a generic ePRO symptom monitoring workflow to create a site-specific version: (1) design a generic ePRO symptom monitoring workflow through a qualitative study with key stakeholders; (2) conduct co-design workshops to understand stakeholder preferences regarding a site-specific version; (3) code co-design workshop data using the AACTT framework to produce a provisional site-specific version; (4) conduct a final co-design workshop using the AACTT framework to finalize stakeholder preferences for a site-specific version; and (5) code co-design workshop data using the AACTT framework to produce a final site-specific version. Results Participants (n = 27) included nine patients, four caregivers, four oncologists, four nurses, two pharmacists, two clinic administrators, and two Electronic Medical Record (EMR) analysts. Provisional and final site-specific workflows were generated outlining the key AACTT components for each step of ePRO symptom monitoring. Conclusion We demonstrated the value in using the AACTT to guide the co-design of a site-specific workflow for ePRO symptom monitoring. By describing this process in detail, we will enable others to replicate this process for creating site-specific workflows not only for ePRO symptom monitoring, but for any complex clinical process.

9th National Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Research Conference

https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/centres-institutes/patient-reported-outcomes/events/9th-national-proms-research-conference

Conference: 19th June 2025

at Uo Birmingham #CPROR

Submission deadline: 11th April

The call "PROMising Futures" highlights focal areas for submissions:

Innovative ways to develop and implement PROMs

#ImplementationScience #ImplementationResearch

Presentation of PROMs to clinicians and patients

#Feedback

and the description of the clinical utility of PROMs.

"Implementation Science meets Systems Science: Harnessing the Power of Systems Thinking and System Dynamics for Effective Implementation in Health Sciences"

https://nursing.unibas.ch/de/aktuell/news/

💡 In the SNSF-funded workshop, participants explored and applied systems science approaches to their implementation science projects, receiving valuable feedback during consultation sessions.

Big thanks to Dr. Decouttere & Prof. Vandaele for sharing their expertise! 👏

Implementation Science Webinar Series 2025

Nun im 5. Jahr bietet IMPACT wieder eine Implementation Science Webinar-Serie.

Die vier Veranstaltungen finden am 16. April, 7. Mai, 17. September und 26. November 2025, jeweils von 17:00 bis 18:30 Uhr statt. Internationale Experten geben einen Einblick in verschiedene Bereiche der Implementierungswissenschaft.

https://nursing.unibas.ch/de/aktuell/single/implementation-science-webinar-series-2025/

Die Anmeldung zu den Webinaren ist kostenlos.

#Pflegewissenschaft #Pflege #Nursing #nursres #ImplementationScience

Why guidelines fail: on consequences of the false dichotomy between global and local knowledge in health systems

Global health continues to grapple with a persistent tension between standardized, evidence-based interventions developed by international experts and the contextual, experiential local knowledge held by local health workers. This dichotomy – between global expertise and local knowledge – has become increasingly problematic as health systems face unprecedented complexity in addressing challenges from climate change to emerging diseases.

The limitations of current approaches

The dominant approach privileges global technical expertise, viewing local knowledge primarily through the lens of “implementation barriers” to be overcome. This framework assumes that if only local practitioners would correctly apply global guidance, health outcomes would improve.

This assumption falls short in several critical ways:

The hidden costs of privileging global expertise

When we examine actual practice, we find that privileging global over local knowledge can actively harm health system performance:

- It creates a “capability trap” where local health workers become dependent on external expertise rather than developing their own problem-solving capabilities.

- It leads to the implementation of standardized solutions that may not address the real needs of communities.

- It demoralizes community-based staff who see their expertise and experience consistently undervalued.

- It slows the spread of innovative local solutions that could benefit other contexts.

Evidence from practice

Recent experiences from the COVID-19 pandemic provide compelling evidence for the importance of local knowledge. While global guidance struggled to keep pace with evolving challenges, local health workers had to figure out how to keep health services going:

- Community health workers in rural areas adapted strategies.

- District health teams created new approaches to maintain essential services during lockdowns.

- Facility staff developed creative solutions to manage PPE shortages.

These innovations emerged not from global technical assistance, but from local practitioners applying their deep understanding of community needs and system constraints, and by exploring new ways to connect with each other and contribute to global knowledge.

Towards a new synthesis

Rather than choosing between global and local knowledge, we need a new synthesis that recognizes their complementary strengths. This requires three fundamental shifts:

1. Reframing local knowledge

- Moving from viewing local knowledge as merely contextual to seeing it as a source of innovation.

- Recognizing frontline health workers as knowledge creators, not just knowledge recipients.

- Valuing experiential learning alongside formal evidence.

2. Rethinking technical assistance

- Shifting from knowledge transfer to knowledge co-creation.

- Building platforms for peer learning and exchange.

- Supporting local problem-solving capabilities.

3. Restructuring power relations

- Creating mechanisms for local knowledge to inform global guidance.

- Developing new metrics that value local innovation.

- Investing in local knowledge documentation and sharing.

Practical implications

This new synthesis has important practical implications for how we approach health system strengthening:

Investment priorities

- Funding mechanisms need to support local knowledge creation and sharing

- Technical assistance should focus on building local problem-solving capabilities

- Technology investments should enable peer learning and knowledge exchange

Capacity building

- Training should emphasize critical thinking and adaptation skills as constitutive of new forms of leadership

- Learning programmes should connect peers across contexts

- Evaluation should measure local innovation and problem-solving

Knowledge management (KM)

- Systems need to recognize that knowledge is found in the connections between humans (and increasingly machines), so that improving KM is about more ‘pipes’ (connections) and better quality-ones

- Platforms should therefore enable peer learning and exchange

- Evidence must include practitioner experience and insights

New paths forward

Moving beyond the false dichotomy between global and local knowledge opens new possibilities for strengthening health systems. By recognizing and valuing both forms of knowledge, we can create more effective, resilient, and equitable health systems.

The challenges facing health systems are too complex for any single source of knowledge to address alone. Only by bringing together global expertise and local knowledge can we develop the solutions needed to improve health outcomes for all.

References

Braithwaite, J., Churruca, K., Long, J.C., Ellis, L.A., Herkes, J., 2018. When complexity science meets implementation science: a theoretical and empirical analysis of systems change. BMC Med 16, 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1057-z

Farsalinos, K., Poulas, K., Kouretas, D., Vantarakis, A., Leotsinidis, M., Kouvelas, D., Docea, A.O., Kostoff, R., Gerotziafas, G.T., Antoniou, M.N., Polosa, R., Barbouni, A., Yiakoumaki, V., Giannouchos, T.V., Bagos, P.G., Lazopoulos, G., Izotov, B.N., Tutelyan, V.A., Aschner, M., Hartung, T., Wallace, H.M., Carvalho, F., Domingo, J.L., Tsatsakis, A., 2021. Improved strategies to counter the COVID-19 pandemic: Lockdowns vs. primary and community healthcare. Toxicology Reports 8, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2020.12.001

Jerneck, A., Olsson, L., 2011. Breaking out of sustainability impasses: How to apply frame analysis, reframing and transition theory to global health challenges. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 1, 255–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2011.10.005

Salve, S., Raven, J., Das, P., Srinivasan, S., Khaled, A., Hayee, M., Olisenekwu, G., Gooding, K., 2023. Community health workers and Covid-19: Cross-country evidence on their roles, experiences, challenges and adaptive strategies. PLOS Glob Public Health 3, e0001447. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001447

Yamey, G., 2012. What are the barriers to scaling up health interventions in low and middle income countries? A qualitative study of academic leaders in implementation science. Global Health 8, 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8603-8-11

Share this:

#climateChangeAndHealth #decolonization #evidenceBasedInterventions #expertise #globalHealth #healthSystems #implementationScience #localKnowledge

The capability trap: Nobody ever gets credit for fixing problems that never happened

Here is a summary of the key points from the article “Nobody ever gets credit for fixing problems that never happened: creating and sustaining process improvement”. Overview Core causal loops The capability trap The “capability trap” refers to the downward spiral organizations can get caught in, where attempting to boost performance by pressuring people to “work harder” actually erodes process capability over time. This trap works through a few key mechanisms: Key takeaway for learning leaders Learning leaders must understand the systemic traps identified in the article that underly failed improvement initiatives and facilitate mental model shifts. This help build sustainable, effective learning programs to be realized through productive capability-enhancing cycles. Key takeaway for immunization leaders It is reasonable to hypothesize that poor health worker performance is a symptom rather than the cause of poor immunization programme performance. Short-term decisions, often responding to top-down targets and donor requirements, hurt capability ... Read More

How can we reliably spread evidence-based practices at the speed and scale modern health challenges demand?

At a symposium of the American Society for Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) Annual Meeting, I explored how peer learning could help us tackle five critical challenges that limit effectiveness in global health.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q08dbbzUzzc

For epidemiologists working on implementation science, peer learning provides a new path for solving one of global health’s most persistent challenges: how to reliably spread evidence-based practices at the speed and scale modern health challenges demand.

The evidence suggests we should view peer learning not just as a training approach, but as a mechanism for viral spread of effective practices through health systems.

How do we get to attribution?

Of course, an epidemiologist will want to know if and how improved health outcomes can be attributed to peer learning interventions.

The Geneva Learning Foundation (TGLF) addresses this fundamental challenge in implementation science – proving attribution – through a three-stage process that combines quantitative indicators with qualitative validation.

The process begins with baseline health indicators relevant to each context (such as vaccination coverage rates, if it is immunization), which are then tracked through regular “acceleration reports” that capture both metrics and implementation progress.

Rather than assuming causation from correlation, participants must explicitly rate the extent to which they attribute observed improvements to their intervention.

The critical innovation comes in the third stage: those claiming attribution must “prove it” to the community of peers, by providing specific evidence of how their actions led to the observed changes – a requirement that both controls for self-reporting limitations and generates rich qualitative data about implementation mechanisms.

This methodology has proven particularly valuable in complex interventions where randomized controlled trials may be impractical or insufficient.

What are examples of peer learning in action?

Here are three examples from The Geneva Learning Foundation’s work that demonstrate scale, reach, and sustainability.

Within four weeks, a single Teach to Reach cohort of 17,662 health workers across over 80 countries generated 1,800 context-specific experiences describing the “how” of implementation, especially at the district and community levels.

In Côte d’Ivoire, working with Gavi and The Geneva Learning Foundation, the national immunization team used TGLF’s model to support community engagement. Within two weeks, over 500 health workers representing 85% of the country’s districts had begun implementing locally-led innovations. 82% of participants said they would use TGLF’s model for their own needs, without requiring any further assistance or support.

In TGLF’s COVID-19 Peer Hub, 30% of participants successfully implemented recovery plans within three months – a rate seven times higher than a control group that did not use TGLF’s model.

Participants who actively engaged with peers were not only more likely to report successful implementation, but could demonstrate concrete evidence of how peer interactions contributed to their success, creating a robust framework for understanding not just whether interventions work, but how and why they succeed or fail across different contexts.

Quantifying learning

Using a simple methodology that measures learning efficacy across five key variables – scalability, information fidelity, cost effectiveness, feedback quality, and uniformity – we calculated that properly structured peer learning networks achieve an efficacy score of 3.2 out of 4, significantly outperforming both traditional cascade training (1.4) and expert coaching (2.2).

But the real breakthrough came when considering scale. When calculating the Efficacy-Scale Score (ESS) – which multiplies learning efficacy by the number of learners reached – the differences became stark:

- Peer Learning: 3,200 (reaching 1,000 learners)

- Cascade Training: 700 (reaching 500 learners)

- Expert Coaching: 132 (reaching 60 learners)

Learn more: Calculating the relative effectiveness of expert coaching, peer learning, and cascade training

The mathematics of scale

For epidemiologists, the mechanics of this scaling effect may feel familiar.

In traditional expert-led training, if N is the total number of learners and M is the number of available experts who can each effectively coach K learners, we quickly hit a ceiling where N far exceeds M×K.

TGLF’s model transforms this equation by structuring interactions so each learner gives and receives feedback from exactly three peers, guided by expert-designed rubrics.

This creates a linear scaling pattern where total learning interactions = 3N, allowing for theoretically unlimited scale while maintaining quality through structured feedback loops.

Information loss and network resilience

One of the most interesting findings concerns information fidelity. In cascade training, knowledge degradation follows a predictable pattern:

where Kn is the knowledge at the nth level of the cascade and α is the loss rate at each step. This explains why cascade training, despite its theoretical appeal, consistently underperforms.

In contrast, TGLF’s peer learning-to-action networks showed remarkable resilience. By creating multiple pathways for knowledge transmission and building in structured feedback loops, the system maintains high information fidelity even at scale.

Learn more: Why does cascade training fail?

References

Arling, P.A., Doebbeling, B.N., Fox, R.L., 2011. Improving the Implementation of Evidence-Based Practice and Information Systems in Healthcare: A Social Network Approach. International Journal of Healthcare Information Systems and Informatics 6, 37–59. https://doi.org/10.4018/jhisi.2011040104

Hogan, M.J., Barton, A., Twiner, A., James, C., Ahmed, F., Casebourne, I., Steed, I., Hamilton, P., Shi, S., Zhao, Y., Harney, O.M., Wegerif, R., 2023. Education for collective intelligence. Irish Educational Studies 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2023.2250309

Watkins, K.E., Sandmann, L.R., Dailey, C.A., Li, B., Yang, S.-E., Galen, R.S., Sadki, R., 2022. Accelerating problem-solving capacities of sub-national public health professionals: an evaluation of a digital immunization training intervention. BMC Health Serv Res 22, 736. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08138-4

Share this:

#AmericanSocietyForTropicalMedicineAndHygiene #ASTMH #attribution #cascadeTraining #globalHealth #implementationScience #peerLearning #TheGenevaLearningFoundation #TropMed24

What learning science underpins peer learning for Global Health?

Watch Reda Sadki’s presentation at the Annual Meeting of the American Society for Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) Symposium on 19 October 2023 Most significant learning that contributes to improved performance takes place outside of formal training. It occurs through informal and incidental forms of learning between peers. Effective use of peer learning requires realizing how much we can learn from each other (peer learning), experiencing the power of defying distance to solve problems together (remote learning), and feeling a growing sense of belonging to a community (social learning), emergent across country borders and health system levels (networked learning). At the ASTMH annual meeting Symposium organized by Julie Jacobson, two TGLF Alumnae, María Monzón from Argentina and Ruth Allotey from Ghana, will be sharing their analyses and reflections of how they turned peer learning into action, results, and impact. In his presentation, Reda Sadki, president of The Geneva Learning Foundation ... Read More

Keep things simple if you want things done.

Here is my rule of 10: 10mg of empagliflozin, 10mg of ramipril, 10mg of rosuvastatin, 10mg of ezetimibe and 10mg finerenone is a solid 10/10 for cardiovascular and kidney disease in diabetes. It is potent combo and easy to remember.#implementationscience