I just had a brief conversation involving how reads work under #ZFS, how flash-based SSDs actually perform, and how this means cache devices are only rarely useful. Thought I would elaborate a bit and share more broadly.

First, a quick description of ARC, the Adaptive Replacement Cache. It’s the ZFS read caching layer. It involves an index and two data pools. One pool stores most recently used data. The other pool stores most frequently used data, even if it wasn’t used recently. Any time data is read, the system checks the ARC index to see if the data is cached. If it is, the copy in RAM is returned. Otherwise, the storage is read. For most workloads, this combination works *really* well. The data you request is almost always in RAM, and only a small percentage of requests need to hit the much slower storage.

ZFS cache devices are often called L2ARC. They don’t really use ARC logic, though. Instead, cache devices are populated by data which is about to fall out of ARC. This is a constant trickle of data (usually about 10 MB/s) being written to the cache device. An index of what data is on the cache device is also stored in RAM. The amount of RAM spent on the index depends on the record size (100 GB of small records costs more to index than 100 GB of big records). Now, when data is requested, the system checks the ARC index, then the cache index, then the storage. If the cache index says the cache device has the data, it’s read from there rather than from the storage.

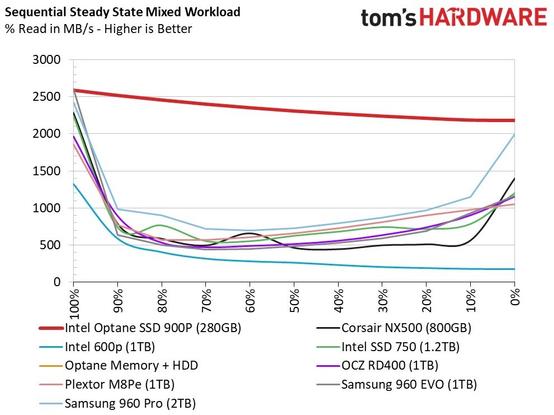

Everybody who has dealt with spinning disks knows they aren’t very good at reading and writing at the same time. The heads have to seek all over the disk. Unfortunately, SSDs have a very similar problem. If you give them an all-read or all-write workload, they’re really fast, but even a 10% mix and performance craters. Tom’s Hardware did an excellent test of an Optane drive a few years ago ( https://www.tomshardware.com/reviews/intel-optane-ssd-900p-3d-xpoint,5292-2.html )which demonstrated this problem. I’ve attached one of the more interesting performance graphs.

Note that at 90% read workload, performance of the non-Optane drives drops to less than half of what it is at 100% read. ZFS cache vdevs have a constant low-level write workload. They’ll never be above 90% read workload.

Meanwhile, the devices used to provide capacity to a ZFS pool only receive write workload when a transaction group closes. By default, this is every five seconds, but it can be less if the transaction group fills early. The rest of the time, there’s no writing. This leaves them free for 100% read workload for seconds at a time, even under heavy write load.

The result of this is that to provide benefit, a cache device has to be significantly faster than the pool devices. With SATA SSDs providing capacity, even an NVMe SSD is probably too slow to be a good cache device.