#Saturn #Voyager #Enceladus

#Saturn #Voyager #Enceladus

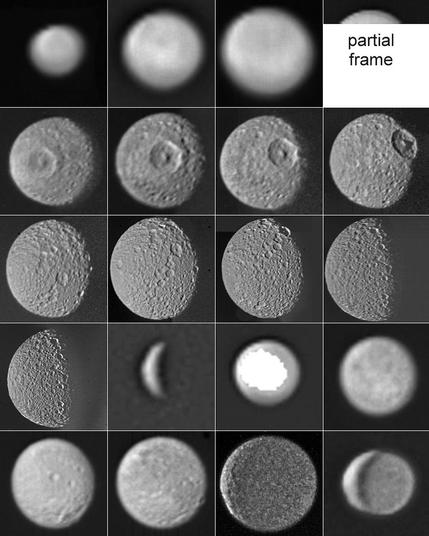

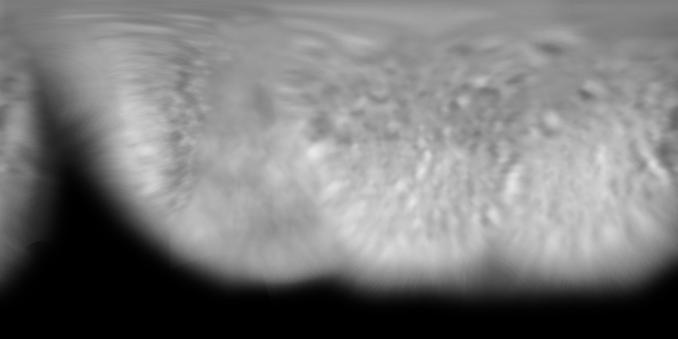

Let's have a look at those Voyager 1 images of Enceladus - the 3 best ones. They all show dark patches and light whisps, a first look at the 'tiger stripe' region at the south pole. Nothing in these images hints at what is going on there, but it is intriguing. Voyager 2 didn't see this area so we had to wait for Cassini to really get to know it.

I think we really need both kinds of map because they are telling us different things. Incidentally, if you want to see a modern (Cassini-based) map, go here:

https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/images/pia12783-the-enceladus-atlas/

Time to be moving on... where next on our itinerary?

It's not great, but it was only 3 images. Here's a better application of it with Mars Pathfinder imagesby Tim Parker of JPL:

https://mpf.digitec.net/parker/highres-stereo.html

Now imagine taking a 6-frame multispectral sequence of a little moon and doing the same. It makes a difference. I first did this in my 1996 paper on Hyperion:

https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/BF00118722.pdf

(I hope no sign-in is necessary for you with this link)

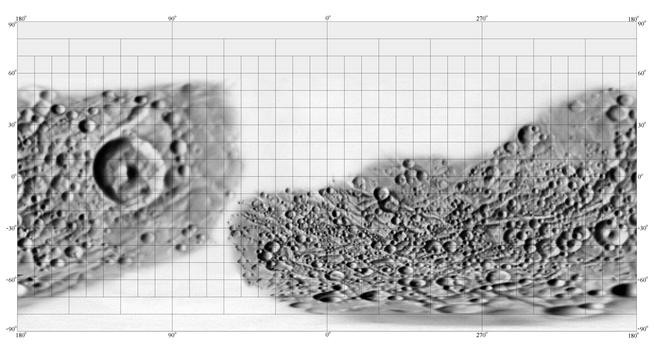

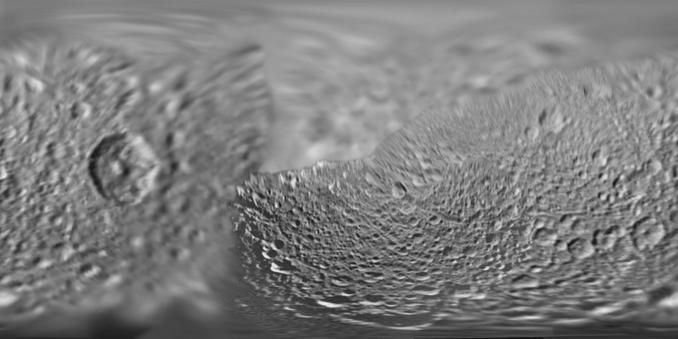

At last, here is the composite map using Voyager 1 and 2 images of little Mimas. Most of the surface is covered. You might like to compare it with this Cassini map:

https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/images/pia17214-mimas-global-map-june-2017/

I pointed out that my map and the USGS map don't agree in crater positions in places. Neither of them match this very well. Pointing uncertainties, an incorrect shape model of Mimas in early mapping (not really a sphere) and other errors affect both of them. #Saturn #Voyager #Mimas

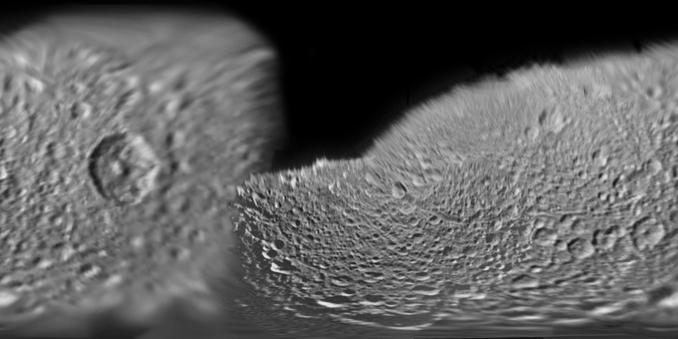

Here is the northern hemisphere of Mimas in that full Voyager mosaic.

These maps are never going to look great compared with Cassini imaging. My intention here is to show how some details not noticed at the time were indeed present in Voyager images. We will see some more of these in the coming days. #maps #Saturn #Voyager #Mimas

Those images of Dione are hiding something. Here is one of the distant images enlarged to show an oblique view of a 300 km diameter circular impact basin. It's now called Evander. Here is a Cassini map with names:

https://asc-planetarynames-data.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/dione_comp.pdf

And here is my 2002 LPSC abstract on its discovery:

https://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2002/pdf/1553.pdf

I presented this but never wrote it up, being bogged down in much bigger projects at the time (and ever since).

Here is a modern (i.e. Cassini) map of Rhea with feature names:

https://asc-planetarynames-data.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/rhea_comp.pdf

If you want to explore all such solar system names, go here:

https://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/

Use the menu bar underneath the banner image to explore names on maps of many worlds. You will notice asteroids are included. But interestingly, for some reason, not comets. I don't know why not. Even Rosetta's amazing comet 67P, which did get names in publications, never got official status for them. #maps #planets

Cassini surmised, correctly, that Iapetus had a dark side and a bright side, and could be seen easily only when the bright side was facing the observer. As the visibility was always good on the same side of the planet he concluded Iapetus was in synchronous rotation like our Moon.

Here is one of the Voyager 1 images of the area I want to examine. Not much to see... that dark ring is presumably a crater but we don't see it very clearly. But we will see more... #Saturn #Voyager #iapetus

The longer, narrower linear feature in the previous image is suspiciously like the famous equatorial ridge of Iapetus but I can't bring myself to believe it is. The other linear object doesn't seem to be real. But the basin is real - here are some Cassini images from orbit 1. The two on the left are the same, raw and stretched. The two on the right show another big crater further west. Voyager didn't see that.

I think I will leave these moons now and move on.