Can São Tomé make its entire country a nature reserve?

A few years ago there was an unusual campaign to make London the world’s first national park city. London, especially south of the river, has enough green spaces to just about make that plausible. In 2019 they achieved it, though I don’t really know what difference it is making. Here’s something more impressive however: the first country to declare all of its territory a biosphere reserve.

It was announced by UNESCO recently as part of a new cohort of reserves, and São Tomé and Principe stands out. It’s the first time a nation has drawn the nature reserve boundary around its entire border and devoted the whole country to conservation.

How’s that going to work? Is that even possible? Can you extend the rules of a nature reserve that far?

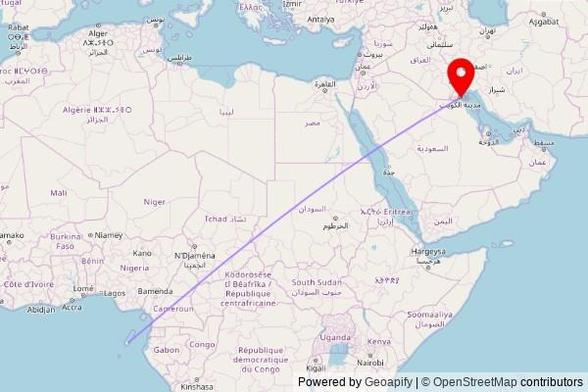

If you can do it anywhere, it can be here. São Tomé and Principe is a small island state spooned in the Gulf of Guinea, and you can manage the biodiversity of islands more carefully. It’s also a small enough land mass to be realistic – it’s the second smallest country in Africa after the Seychelles. The population is small too. At 208,000, it’s pretty similar to the town of Luton where I live.

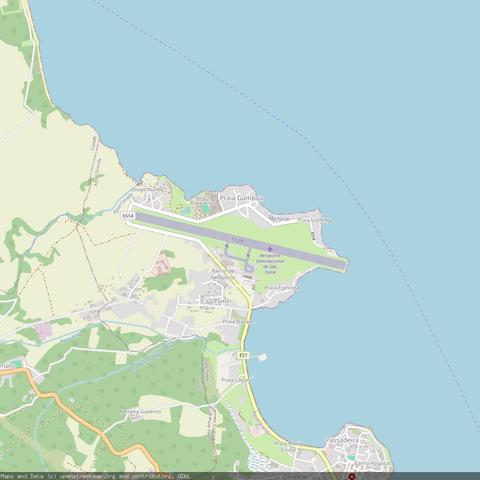

To make things easier, 90% of that population is based in or around the capital of Cidade de São Tomé. That’s a lot of sparsely occupied territory to work with, and one of the reasons that so many people live in the city is that much of the country is made up of steep volcanic valleys and ridges. These aren’t hospitable to human settlements, and are great places for wildlife to be left alone. You’ll find plenty there, with lots of birds, rare trees and flowers, and a haven for sea turtles.

UNESCO biosphere reserves prioritise conservation, but they don’t follow the traditional (and often colonial) pattern of shutting the doors to local people in order to preserve an idealised vision of the wild. Areas also commit to sustainable development within the zone, and the sites are also used for education and research. According to UN’s guidelines for managing one, biosphere reserves have a pretty broad brief: “Fostering the harmonious integration of people and nature for sustainable development through participatory dialogue, knowledge sharing, poverty reduction, human well-being improvements, respect for cultural values and by improving society’s ability to cope with climate change.”

There’s an explicit mention of poverty there, which is important in a country where most people are on very low incomes. There’s also a commitment to participatory management, which protects human rights. It suggests that you could run the whole of a smaller country within those guidelines. Besides, São Tomé and Principe have a headstart. Principe, the smaller of the two main islands, was designated a UNESCO biosphere reserve in 2012. Technically this is an extension, and they have practice. It looks feasible and it’s good PR – a visible commitment to its natural environment at a time when tourism is the country’s most promising growth industry.

This is important, because there’s a lurking presence in the background. With limited options for generating significant foreign income, successive governments have been eyeing offshore oil and gas. Neighbouring countries have made a fortune this way along the same coastline. It’s quite likely that São Tomé and Principe has oil and gas too. Several of the oil giants think so, including Total, Shell and Brazil’s Petrobras, and all three have signed exploration deals. Shell has a test well and expects to be able to announce results this year.

So far São Tomé has produced zero oil, and what happens next will determine the authenticity of its UNESCO designation. Ideally it marks a choice to look elsewhere and direct its future economy towards sustainability – albeit compromised by having to fly tourists in (see also the Maldives). On the other hand, we could end up with a UNESCO biosphere reserve that is also an emerging oil and gas exporter. The country’s contribution to climate change is currently minuscule. That would rapidly change if the oil majors hit black gold, it would leave the biosphere reserve status as a sick joke, a greenwashing project on an audacious scale.

At the moment it looks like the government wants to have it both ways. I haven’t seen any sign that they are pausing oil and gas exploration – a new investment in offshore exploration was signed just three weeks before UNESCO’s announcement. But these are of course entirely contraditory policies. As a small island state, São Tomé and Principe is highly vulnerable to climate change. You cannot commit to preserving your wildlife while amplifying the threat to it.

São Tomé and Principe’s best known landmark is the Pico Cao Grande, surely one of the world’s most joyously eccentric rock formations. When it comes to the UNESCO reserve status, should we read it as a big thumbs up from the rainforest? Or is that the nation’s oil and gas hopes, sticking up out of the greenery like a sore thumb?